Gin and monotonic

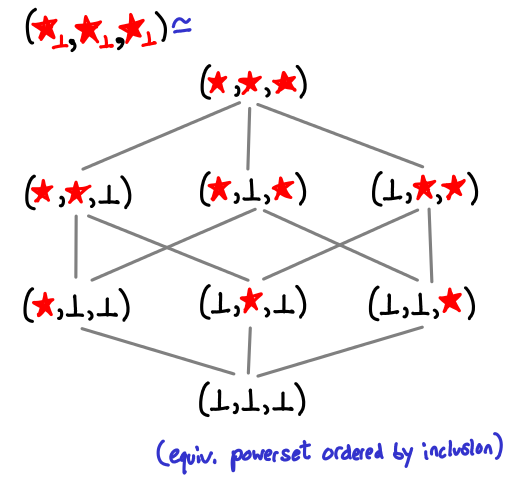

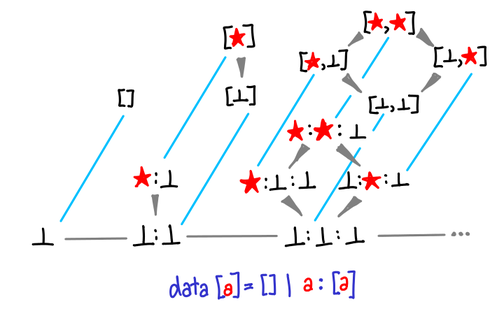

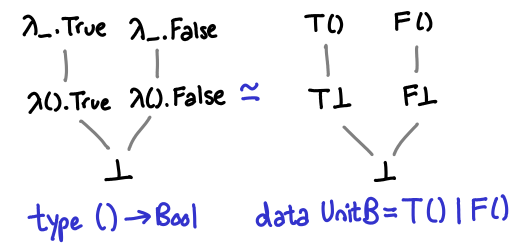

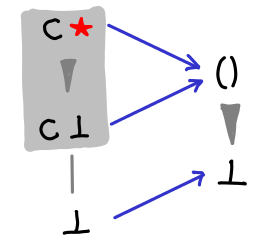

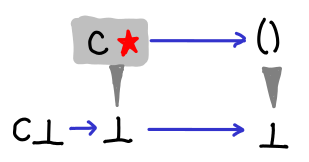

Last time we looked the partial orders of values for data types. There are two extra things I would like to add: an illustration of how star-subscript-bottom expands and an illustration of list without using the star-subscript-bottom notation.

Here is a triple of star-subscript-bottoms expanded, resulting in the familiar Hasse diagram of the powerset of a set of three elements ordered by inclusion:

And here is the partial order of lists in its full exponential glory (to fit it all, the partial order of the grey spine increases as it goes to the right.)

Now, to today's subject, functions! We've only discussed data types up until now. In this post we look a little more closely at the partial order that functions have. We'll introduce the notion of monotonicity. And there will be lots of pictures.

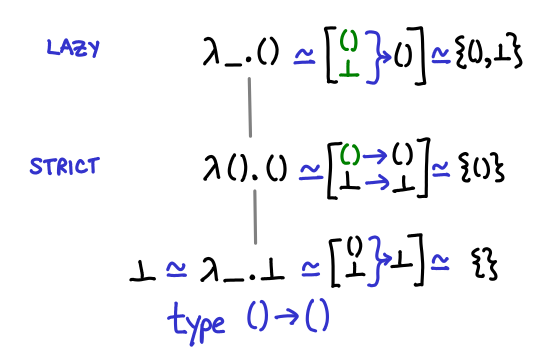

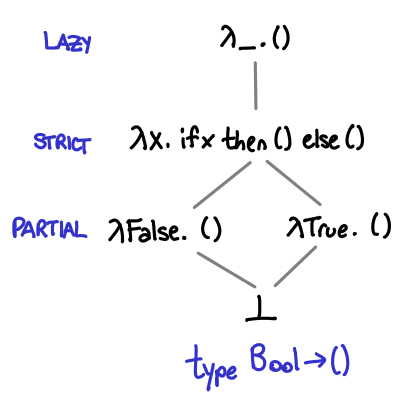

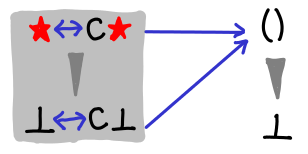

Let's start with a trivial example: the function of unit to unit, () -> (). Before you look at the diagram, how many different implementations of this function do you think we can write?

Three, as it turns out. One which returns bottom no matter what we pass it, one which is the identity function (returns unit if it is passed unit, and bottom if it is passed bottom), and one which is const (), that is, returns unit no matter what it is passed. Notice the direct correspondence between these different functions and strict and lazy evaluation of their argument. (You could call the bottom function partial, because it's not defined for any arguments, although there's no way to directly write this and if you just use undefined GHC won't emit a partial function warning.)

In the diagram I've presented three equivalent ways of thinking about the partial order. The first is just terms in the lambda calculus: if you prefer Haskell's notation you can translate λx.x into \x -> x. The second is a mapping of input values to output values, with bottom explicitly treated (this notation is good for seeing bottom explicitly, but not so good for figuring out what values are legal—that is, computable). The third is merely the domains of the functions: you can see that the domains are steadily getting larger and larger, from nothing to the entire input type.

At this point, a little formality is useful. We can define a partial order on a function as follows: f ≤ g if and only if dom(f) (the domain of f, e.g. all values that don't result in f returning bottom) ⊆ dom(g) and for all x ∈ dom(f), f(x) ≤ g(x). You should verify that the diagram above agrees (the second condition is pretty easy because the only possible value of the function is ()).

A keen reader may have noticed that I've omitted some possible functions. In particular, the third diagram doesn't contain all possible permutations of the domain: what about the set containing just bottom? As it turns out, such a function is uncomputable (how might we solve the halting problem if we had a function () -> () that returned () if its first argument was bottom and returned bottom if its first argument was ()). We will return to this later.

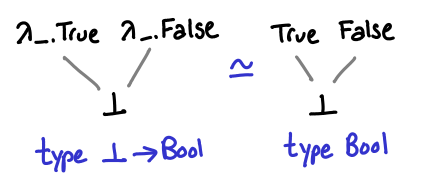

Since () -> () has three possible values, one question to ask is whether or not there is a simpler function type that has fewer values? If we admit the empty type, also written as ⊥, we can see that a -> ⊥ has only one possible value: ⊥.

Functions of type ⊥ -> a also have some interesting properties: they are isomorphic to plain values of type a.

In the absence of common subexpression elimination, this can be a useful way to prevent sharing of the results of lazy computation. However, writing f undefined is annoying, so one might see a () -> a instead, which has not quite the same but similar semantics.

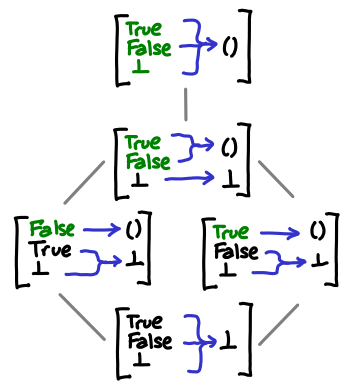

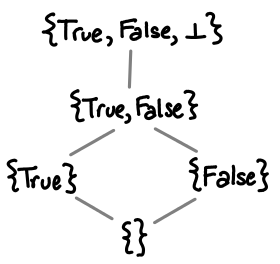

Up until this point, we've considered only functions that take ⊥ or () as an argument, which are not very interesting. So we can consider the next possible simplest function: Bool -> (). Despite the seeming simplicity of this type, there are actually five different possible functions that have this type.

To see why this might be the case, we might look at how the function behaves for each of its three possible arguments:

or what the domain of each function is:

These partial orders are complete, despite the fact there seem to be other possible permutations of elements in the domain. Once again, this is because we've excluded noncomputable functions. We will look at this next.

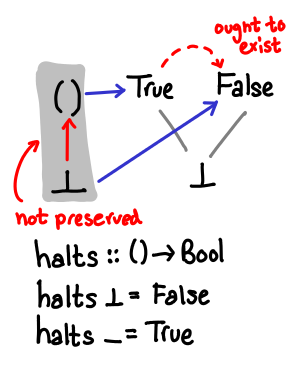

Consider the following function, halts. It returns True if the computation passed to it eventually terminates, and False if it doesn't. As we've seen by fix id, we can think of bottom as a nonterminating computation. We can diagram this by drawing the Hasse diagrams of the input and output types, and then drawing arrows mapping values from one diagram to the other. I've also shaded with a grey background values that don't map to bottom.

It is widely known that the halting problem is uncomputable. So what is off with this perfectly plausible looking diagram?

The answer is that our ordering has not been preserved by the function. In the first domain, ⊥ ≤ (). However, the resulting values do not have this inequality: False ≰ True. We can sum this condition as monotonicity, that is, f is monotonic when if x ≤ y then f(x) ≤ f(y).

Two degenerate cases are worth noting here:

- In the case where f(⊥) = ⊥, i.e. the function is strict, you never have to worry about ⊥ not being less than any other value, as by definition ⊥ is less than all values. In this sense making a function strict is the “safe thing to do.”

- In the case where f(x) = c (i.e. a constant function) for all x, you are similarly safe, since any ordering that was in the original domain is in the new domain, as c ≤ c. Thus, constant functions are an easy way of assigning a non-bottom value to f(⊥). This also makes clear that the monotonicity implication is only one direction.

What is even more interesting (and somewhat un-obvious) is that we can write functions that are computable, are not constant, and yet give a non-⊥ value when passed ⊥! But before we get to this fun, let's first consider some computable functions, and verify monotonicity holds.

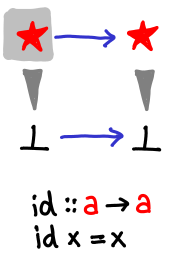

Simplest of all functions is the identity function:

It does so little that it is hardly worth a mention, but you should verify that you're following along with the notation.

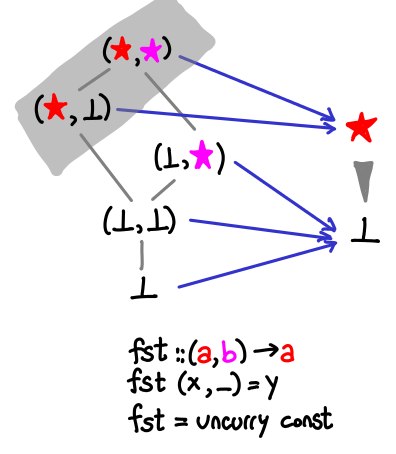

A little less trivial is the fst function, which returns the first element of a pair.

Look and verify that all of the partial ordering is preserved by the function: since there is only one non-bottom output value, all we need to do is verify the grey is “on top of” everything else. Note also that our function doesn't care if the snd value of the pair is bottom.

The diagram notes that fst is merely an uncurried const, so let's look at that next.

We would like to consider the sense of const as a -> (b -> a), a function that takes a value and returns a function. For the reader's benefit we've also drawn the Hasse diagrams of the resulting functions. If we had fixed the type of a or b, there would be more functions in our partial order, but without this, by parametricity there is very little our functions can do.

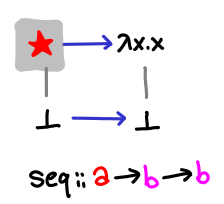

It's useful to consider const in contrast to seq, which is something of a little nasty function, though it can be drawn nicely with our notation.

The reason why the function is so nasty is because it works for any type (it would be a perfectly permissible and automatically derivable typeclass): it's able to see into any type a and see that it is either bottom or one of its constructors.

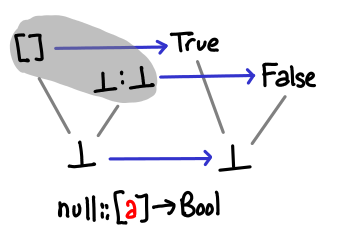

Let's look at some functions on lists, which can interact in nontrivial ways with bottom. null has a very simple correspondence, since what it is really asking is “is this the cons constructor or the null constructor?”

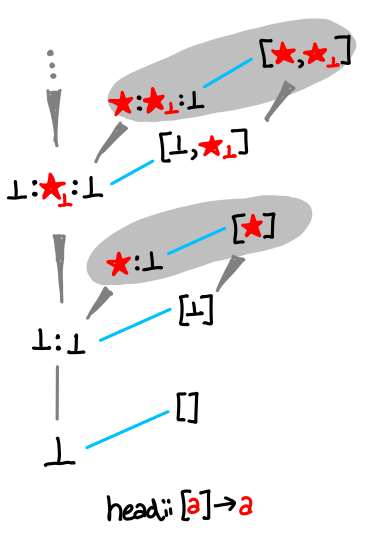

head looks a little more interesting.

There are multiple regions of gray, but monotonicity is never violated: despite the spine which expands infinitely upwards, each leaf contains a maximum of the partial order.

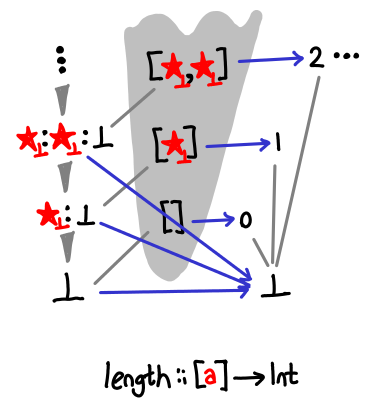

There is a similar pattern about length, but the leaves are arranged a little differently:

Whereas head only cares about the first value of the list not being bottom, length cares about the cdr of the cons cell being null.

We can also use this notation to look at data constructors and newtypes.

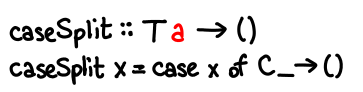

Consider the following function, caseSplit, on an unknown data type with only one field.

We have the non-strict constructor:

The strict constructor:

And finally the newtype:

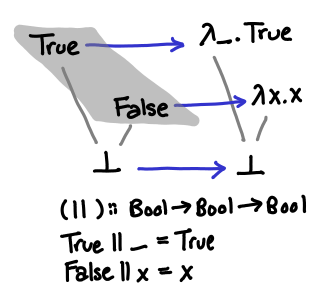

We are now ready for the tour de force example, a study of the partial order of functions from Bool -> Bool, and a consideration of the boolean function ||. To refresh your memory, || is usually implemented in this manner:

Something that's not too obvious from this diagram (and which we would like to make obvious soon) is the fact that this operator is left-to-right: True || ⊥ = True, but ⊥ || True = ⊥ (in imperative parlance, it short-circuits). We'll develop a partial order that will let us explain the difference between this left-or, as well as its cousin right-or and the more exotic parallel-or.

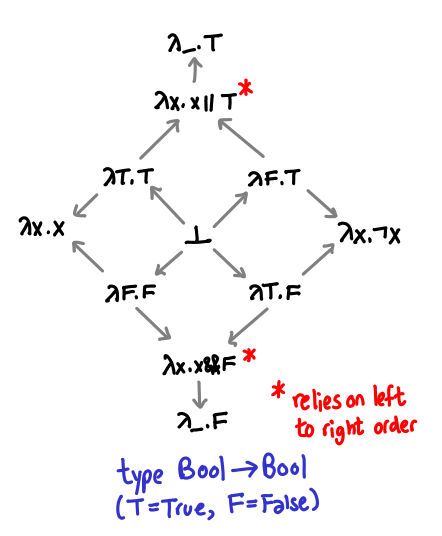

Recall that || is curried: its type is Bool -> (Bool -> Bool). We've drawn the partial order of Bool previously, so what is the complete partial order of Bool -> Bool? A quite interesting structure!

I’ve violated my previously stated convention that more defined types are above other types, in order to demonstrate the symmetry of this partial order. I've also abbreviated True as T and False as F. (As penance, I've explicitly drawn in all the arrows. I will elide them in future diagrams when they're not interesting.)

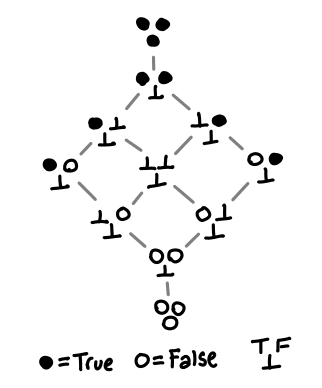

These explicit lambda terms somewhat obscure what each function actually does, so here is a shorthand representation:

Each triple of balls or bottom indicates how the function reacts to True, False and bottom.

Notice the slight asymmetry between the top/bottom and the left/right: if our function is able to distinguish between True and False, there is no non-strict computable function. Exercise: draw the Hasse diagrams and convince yourself of this fact.

We will use this shorthand notation from now on; refer back to the original diagram if you find yourself confused.

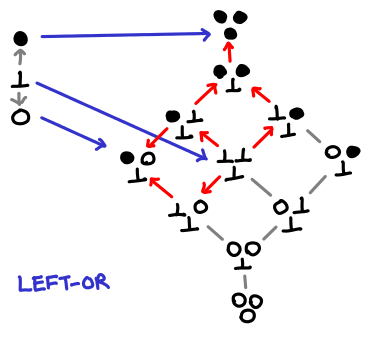

The first order (cough) of business is to redraw the Hasse-to-Hasse diagram of left-or with the full partial order.

Verify that using transitivity we can recover the simplified, partial picture of the partial order. The red arrows indicate the preserved ordering from the original boolean ordering.

The million dollar question is this: can we write a different mapping that preserves the ordering (i.e. is monotonic). As you might have guessed, the answer is yes! As an exercise, draw the diagram for strict-or, which is strict in both its arguments.

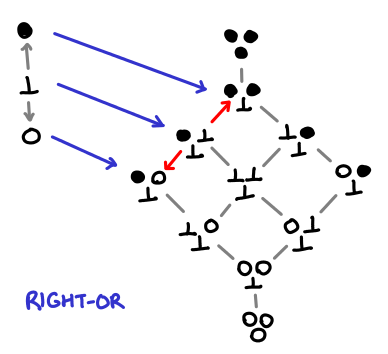

Here is the diagram of right-or:

Notice something really interesting has happened: bottom no longer maps to bottom, but we've still managed to preserve the ordering. This is because the target domain has a rich enough structure to allow us to do this! If this seems a little magical to you, consider how we might write a right-or in Haskell:

rightOr x = \y -> if y then True else x

We just don't look at x until we've looked at y; in our diagram, it looks as if x has been slotted into the result if y is False.

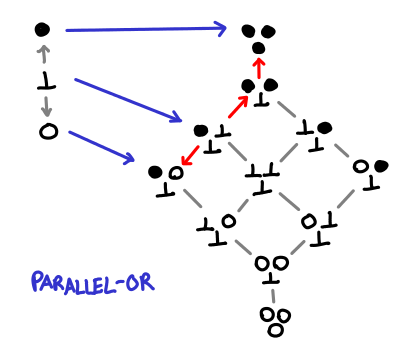

There is one more thing we can do (that has probably occurred to you by now), giving us maximum ability to give good answers in the face of bottom, parallel-or:

Truly this is the farthest we can go: we can't push our functions any further down the definedness chain and we can't move our bottom without changing the strict semantics of our function. It's also not obvious how one would implement this in Haskell: it seems we really need to be able to pattern match against the first argument in order to decide whether or not to return const True. But the function definitely is computable, since monotonicity has not been violated.

The name is terribly suggestive of the correct strategy: evaluate both arguments in parallel, and return True if any one of them returns True. In this way, the Hasse diagram is quite misleading: we never actually return three distinct functions. However, I'm not really sure how to illustrate this parallel approach properly.

This entire exercise has a nice parallel to Karnaugh maps and metastability in circuits. In electrical engineering, you not only have to worry about whether or not a line is 1 or 0, but also whether or not it is transitioning from one to the other. Depending on how you construct a circuit, this transition may result in a hazard even if the begin and end states are the same (strict function), or it may stay stable no matter what the second line dones (lazy function). I encourage an electrical engineer to comment on what strict-or, left-or, right-or and parallel-or (which is what I presume is usually implemented) look like at the transistor level. Parallels like these make me feel that my time spent learning electrical engineering was not wasted. :-)

That's it for today. Next time, we'll extend our understanding of functions and look at continuity and fixpoints.

Postscript. There is some errata for this post.