Hussling Haskell types into Hasse diagrams

Values of Haskell types form a partial order. We can illustrate this partial order using what is called a Hasse diagram. These diagrams are quite good for forcing yourself to explicitly see the bottoms lurking in every type. Since my last post about denotational semantics failed to elicit much of a response at all, I decided that I would have better luck with some more pictures. After all, everyone loves pictures!

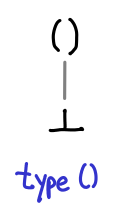

We’ll start off with something simple: () or unit.

Immediately there are a few interesting things to notice. While we normally think of unit as only having one possible value, (), but in fact they have two: () and bottom (frequently written as undefined in Haskell, but fix id will do just as well.) We’ve omitted the arrows from the lines connecting our partial order, so take as a convention that higher up values are “greater than” their lower counterparts.

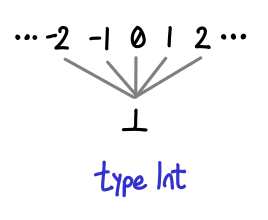

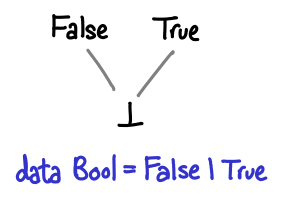

A few more of our types work similarly, for example, Int and Bool look quite similar:

Note that Int without bottom has a total ordering independent of our formulation (the usual -3 is less than 5 affair, alluded to by the Ord instance for Int). However, this is not the ordering you’re looking for! In particular, it doesn’t work if bottom is the game: is two less than or greater than bottom? In this partial ordering, it is “greater”.

It is no coincidence that these diagrams look similar: their unlifted sets (that is, the types with bottom excluded) are discrete partial orders: no element is less than or greater than another.

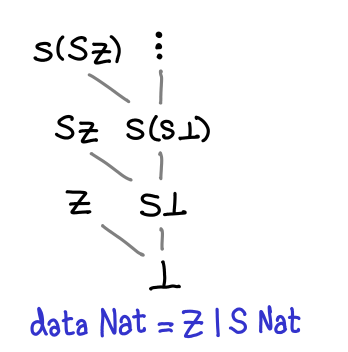

What happens if we introduce data types that include other data types? Here is one for the natural numbers, Peano style (a natural number is either zero or the successor of a natural number.)

We no longer have a flat diagram! If we were in a strict language, this would have collapsed back into the boring partial orders we had before, but because Haskell is lazy, inside every successor constructor is a thunk for a natural number, which could be any number of exciting things (bottom, zero, or another successor constructor.)

We’ll see a structure that looks like this again when we look at lists.

I’d like to discuss polymorphic data types now. In Haskell Denotational semantics wikibook, in order to illustrate these data types, they have to explicitly instantiate all of the types. We’ll adopt the following shorthand: where I need to show a value of some polymorphic type, I’ll draw a star instead. Furthermore, I’ll draw wedges to these values, suggestive of the fact that there may be more than one constructor for that type (as was the case for Int, Bool and Nat). At the end of this section I’ll show you how to fill in the type variables.

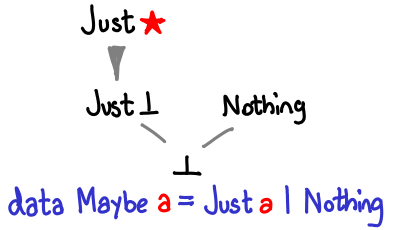

Here is Maybe:

If Haskell allowed us to construct infinite types, we could recover Nat by defining Maybe (Maybe (Maybe ...)).

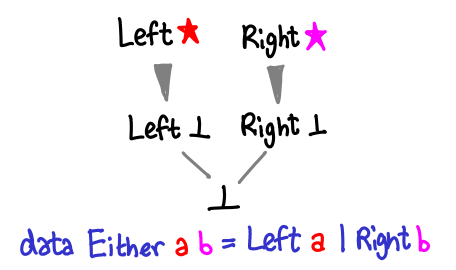

Either looks quite similar, but instead of Nothing we have Right:

Is Left ⊥ greater than or less than Right () in this partial order? It’s a trick question: since they are different constructors they’re not comparable anymore.

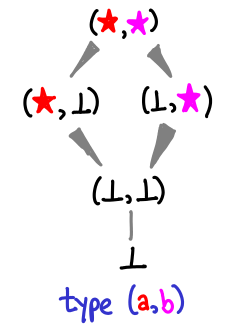

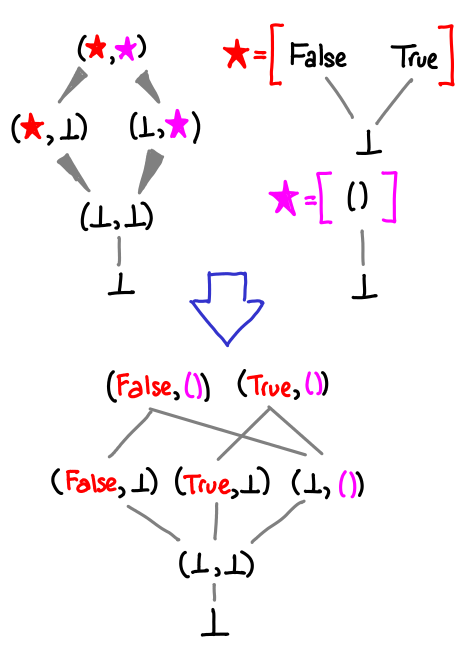

Here’s a more interesting diagram for a 2-tuple:

The values merge back at the very top! This is because while ((), ⊥) is incomparable to (⊥, ()), both of them are less than ((), ()) (just imagine filling in () where the ⊥ is in both cases.)

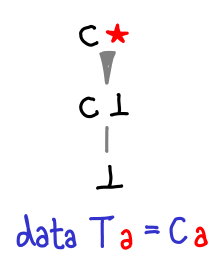

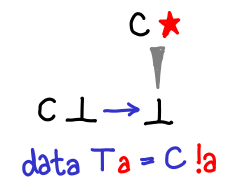

If we admit lazy data structures, we get a lot richer space of possible values than if we’re forced to use strict data structures. If these constructors were strict, our Hasse diagrams would still be looking like the first few. In fact, we can see this explicitly in the difference between a lazy constructor and a strict constructor:

The strict constructor squashes ⊥ and C ⊥ to be the same thing.

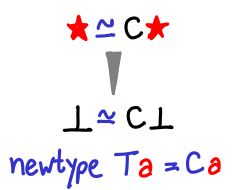

It may also be useful to look at newtype, which merely constructs an isomorphism between two types:

It looks a bit like the strict constructor, but it’s actually not at all the same. More on this in the next blog post.

How do we expand stars? Here’s a diagram showing how:

Graft in the diagram for the star type (excluding bottom, since we’ve already drawn that into the diagram), and duplicate any of the incoming and outgoing arrows as necessary (thus the wedge.) This can result in an exponential explosion in the number of possible values, which is why I’ll prefer the star notation.

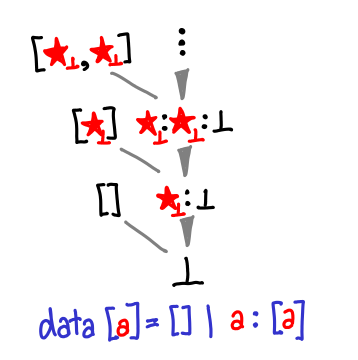

And now, the tour de force, lazy lists:

Update. There’s one bit of extra notation: the stars with subscript ⊥ mean that you’ll need to graft in bottom as well (thanks Anonymous for pointing this out.) Tomorrow we’ll see list expanded in its full, exponential glory.

We almost recover Nat if we set a to be (), but they’re not quite isomorphic: every () might actually be a bottom, so while [()] and [⊥] are equivalent to one, they are different. In fact, we actually want to set a to the empty type. Then we would write 5 as [⊥, ⊥, ⊥, ⊥, ⊥].

Next time, we’ll draw pictures of the partial ordering of functions and illustrate monotonicity.