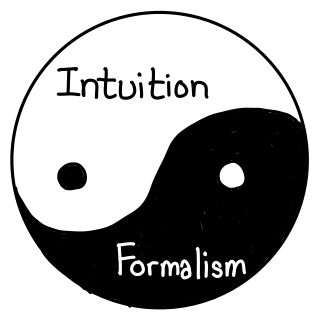

Is it better to teach formalism or intuition?

Note: this is not a discussion of Hilbert's formalism versus Brouwer's intuitionism; I'm using formalism and intuition in a more loose sense, where formalism represents symbols and formal systems which we use to rigorously define arguments (though not logic: a sliding scale of rigor is allowed here), while intuition represents a hand-wavy argument, the mental model mathematicians actually carry in their head.

Formalism and intuition should be taught together.

But as utterly uncontroversial as this statement may be, I think it is worth elaborating why this is the case—the reason we find will say important things about how to approach learning difficult new technical concepts.

Taken in isolation, formalism and intuition are remarkably poor teachers. Have you had the reading a mathematical textbook written in the classic style, all of the definitions crammed up at the beginning of the chapter in what seems like a formidable, almost impenetrable barrier. One thinks, "If only the author had bothered to throw us a few sentences explaining what it is we're actually trying to do here!" But at the same time, I think that we have all also had the experience of humming along to a nice, informal description, when we really haven't learned much at all: when we sit down and try to actually solve some problems, we find these descriptions frustratingly vague. It's easy to conclude that there really is no royal road to intuition, that it must be hard won by climbing the mountains of formalism.

So why is the situation any different when we put them together?

The analogy I like is this: formalism is the object under study, whereas intuition is the results of such a study. Imagine an archaeologist who is attempting to explain to his colleagues a new conclusion he has drawn from a recently excavated artifact. Formalism without intuition is the equivalent of handing over the actual physical artifact without any notes. You can in principle reconstruct the conclusions, but it might take a while. Intuition without formalism, however, is the equivalent of describing your results over the phone. It conveys some information, but not with the resolution or fidelity of actually having the artifact in your hands.

This interpretation explains a bit about how I learn mathematics. For example, most mathematical formalisms aren't artifacts you can "hold in your hand"—at least, not without a little practice. Instead, they are giant mazes, of which you may have visibility of small fragments of at a time. (The parable of the blind men and the elephant comes to mind.) Being able to hold more of the formalism in your head, at once, increases your visibility. Being able to do quick inference increases your visibility. So memorization and rote exercise do have an important part to play in learning mathematics; they increase our facility of handling the bare formalism.

However, when it comes to humans, intuition is our most powerful weapon. With it, we can guess that things are true long before we have any good reason of thinking it is the case. But it is inextricably linked to the formalism which it describes and a working intuition is no where near as easily transferable as a description of a formal system. Intuition is not something you can learn; it is something that assists you as you explore the formalism: "the map of intuition." You still have to explore the formalism, but you shouldn't feel bad about frequently consulting your map.

I've started using this idea for when I take notes in proof-oriented classes, e.g. this set of notes on the probabilistic method (PDF). The text in black is the formal proof; but interspersed throughout there are blue and red comments trying to explicate "what it is we're doing here." For me, these have the largest added value of anything the lecturer gives, since I find these remarks are usually nowhere to be seen in any written notes or even scribe notes. I write them down even if I have no idea what the intuition is supposed to mean (because I'll usually figure it out later.) I've also decided that my ideal note-taking setup is already having all of the formalism written down, so I can pay closer attention to any off-hand remarks the lecturer may be making. (It also means, if I'm bored, I can read ahead in the lecture, rather than disengage.)

We should encourage this style of presentation in static media, and I think a crucial step towards making this possible is easier annotation. A chalkboard is a two-dimensional medium, but when we LaTeX our presentation goes one-dimensional, and we rely on the written word to do most of the heavy lifting. This is fine, but a bit of work, and it means that people don't do it as frequently as we might like. I'm not sure what the best such system would look like (I am personally a fan of hand-written notes, but this is certainly not for everyone!), but I'm optimistic about the annotated textbooks that are coming out from the recent spate of teaching startups.

For further reading, I encourage you to look at William Thurston's essay, On proof and progress in mathematics, which has had a great influence on my thoughts in this matter.