Databases are categories

Update. The video of the talk can be found here: Galois Tech Talks on Vimeo: Categories are Databases.

On Thursday Dr. David Spivak presented Categories are Databases as a Galois tech talk. His slides are here, and are dramatically more accessible than the paper Simplicial databases. Here is a short attempt to introduce this idea to people who only have a passing knowledge of category theory.

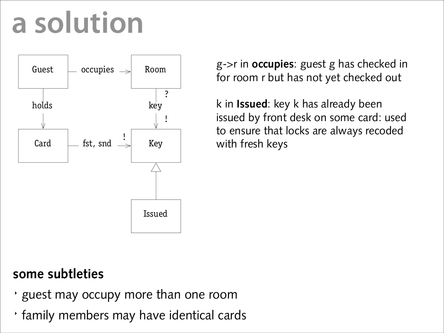

An essential exercise when designing relational databases is the practice of object modeling using labeled graphs of objects and relationships. Visually, this involves drawing a bunch of boxes representing the objects being modeled, and then drawing arrows between the objects showing relationships they may have. We can then use this object model as the basis for a relational database schema.

An example model from a software engineering class is below:

With the image of a object model in your head, consider Wikipedia's definition of a category:

In mathematics, a category is an algebraic structure consisting of a collection of "objects", linked together by a collection of "arrows" that have two basic properties: the ability to compose the arrows associatively and the existence of an identity arrow for each object.

The rest of the definition may seem terribly abstract, but hopefully the bolded section seems to clearly correspond to the picture of boxes (objects) and arrows we drew earlier. Perhaps...

Unfortunately, a directed graph is not quite a category; the secret sauce that makes a category a category are those two properties on the arrows, associative composition and identity, and if we really want to strengthen our claim that a schema is a category, we'll need to demonstrate these.

Recall that our arrows are "relations," that is, "X occupies Y" or "X is the key for Y". Our category must have an identity arrow, that is, some relation "X to X". How about, "X is itself X", an almost vacuous statement, but one most certainly true. Identity arrow, check.

We also need to show associative composition of arrows. Composition of two arrows is much like they showed you when they were teaching you vector algebra: you take the head of one arrow (X to Y) and smush it with the tail of another (Y to Z), and you get another arrow (X to Z). If a "book has an author" and "an author has a favorite color", I can say "the book's author has a favorite color". This composed statement doesn't care who the author was... just what his favorite color is. In fact,

That is, one of the fundamental features of a category, a feature that any nice result from pure category theory uses as if it were intuitively obvious, is one of the very techniques that does not seem obvious to someone reading about JOINs in the second half of a database tutorial.

(Aside. A foreign key relationship is intrinsically many to one: a foreign key field can only point to one record in another table, but many rows can have that field pointing to the same record. When doing relational modeling, we will frequently use many-to-many or one-to-many relationships. Any database administrator knows, however, that we can simply rewrite these into many to one relationships (reversing the arrow in the case of one-to-many and introducing a new table for many-to-many).)

When we have a schema, we also want to have data to fill the schema. As it turns out, this also fits into a category-theoretic framework too, although a full explanation is out of scope for this post (I suggest consulting the slides.)

Why do you care? There are some good reasons mentioned by Spivak:

I'll mention one of my own: SQL, while messy, is precise; it can be fed into a computer and turned into a databases that can do real work. On the other hand, relational models are high level but kind of mushy; developers may complain that drawing diagrams with arrows doesn't seem terribly rigorous and that the formalism doesn't really help them much.

Category theory is precise; it unambiguously assigns meaning and structure to the relations, the laws of composition define what relations are and aren't permissible. Category theory is not only about arrows (if it was it'd be pretty boring); rather, it has a rich body of results from many fields expressed in a common language that can "translated" into database-speak. In many cases, important category theory notions are tricky techniques in database administrator folklore. When you talk about arrows, you're talking a lot more than arrows. That's powerful!