April 12, 2010Earlier in January, I blogged some first impressions about the VX-8R. It’s now three months later, and I’ve used my radio on some more extensive field tests. I’m considering selling my VX-8R for a 7R, for the following reasons:

- I generally need five hours of receive with medium transmission. I only get about 3.5 hours worth of receive with the standard VX-8R battery. This is not really acceptable. (At risk of being “get off my lawn”, Karl Ramm comments that his old Icom W32 from the 90s got 12 hours of receive.)

- The AA battery adapter is laughable, giving maybe 20min of receive time before flagging. The ability to run digital cameras on AA batteries had given me the false impression that I’d be able to do the same for a radio, really this adapter is only fit for emergency receive situations.

- The remaining battery indicator unreliable, going from 8.5V to 7.5V, and then dropping straight to zero. This is the defect I sent mine back in for last time, but I saw this problem in the replacement, and a friend confirmed that he saw the same on his.

- The radio gets quite hot during operation. I’d never noticed the temperature with the 7R.

- Everyone else around here owns a 7R, which severely limits the swappability of various components (in particular, batteries).

I really am going to miss the dedicated stereo jack and slimmer (and, in my opinion, better) interface, but these really are deal breakers. C’ést la vie.

April 9, 2010Two people have asked me how drew the diagrams for my previous post You Could Have Invented Zippers, and I figured I’d share it with a little more elaboration to the world, since it’s certainly been a bit of experimentation before I found a way that worked for me.

Diagramming software for Linux sucks. Those of you on Mac OS X can churn out eye-poppingly beautiful diagrams using OmniGraffle; the best we can do is some dinky GraphViz output, or maybe if we have a lot of time, a painstakingly crafted SVG file from Inkscape. This takes too long for my taste.

So, it’s hand-drawn diagrams for me! The first thing I do is open my trusty Xournal, a high-quality GTK-based note-taking application written by Denis Auroux (my former multivariable calculus professor). And then I start drawing.

Actually, that’s not quite true; by this time I’ve spent some time with pencil and paper scribbling diagrams and figuring out the layout I want. So when I’m on the tablet, I have a clear picture in my head and carefully draw the diagram in black. If I need multiple versions of the diagram, I copy paste and tweak the colors as I see fit (one of the great things about doing the drawing electronically!) I also shade in areas with the highlighter tool. When I’m done, I’ll have a few pages of diagrams that I may or may not use.

From there, it’s “File > Export to PDF”, and then opening the resulting PDF in Gimp. For a while, I didn’t realize you could do this, and muddled by using scrot to take screen-shots of my screen. Gimp will ask you which pages you want to import; I import all of them.

Each page resides on a separate “layer” (which is mildly useless, but not too harmful). I then crop a logical diagram, save-as the result (asking Gimp to merge visible layers), and then undo to get back to the full screen (and crop another selection). When I’m done with a page, I remove it from the visible layers, and move on to the next one.

When it’s all done, I have a directory of labeled images. I resize them as necessary using convert -resize XX% ORIG NEW and then dump them in a public folder to link to.

Postscript. Kevin Riggle reminds me not to mix green and red in the same figure, unless I want to confuse my color blind friends. Xournal has a palette of black, blue, red, green, gray, cyan, lime, pink, orange, yellow and white, which is a tad limiting. I bet you can switch them around, however, by mucking with predef_colors_rgba in src/xo-misc.c

April 7, 2010In the beginning, there was a binary tree:

struct ctree { // c for children

int val;

struct ctree *left;

struct ctree *right;

}

The flow of pointers ran naturally from the root of the tree to the leaves, and it was easy as blueberry pie to walk to the children of a node.

Unfortunately, given a node, there was no good way to find out its parent! If you only needed efficient parent access, though, you could just use a single pointer in the other direction:

struct ptree { // p for parent

int val;

struct ptree *parent;

}

The flow of pointers then ran from the leaves of the tree to the root:

And of course, put together, you could have the best of both worlds:

struct btree {

int val;

struct btree *parent;

struct btree *left;

struct btree *right;

}

Our data structure had become circular, but as a result we had extremely efficient ways to walk up and down the tree, as well as insert, delete and move nodes, simply by mutating the relevant pointers on our node, its children and its parent.

Trouble in paradise. Pointer tricks are fine and good for the mutable story, but we want immutable nodes. We want nodes that won’t change under our nose because someone else decided to muck around the pointer.

In the case of ctree, we can use a standard practice called path copying, where we only need to change the nodes in the path to the node that changed.

In fact, path copying is just a specific manifestation of the rule of immutable updates: if you replace (i.e. update) something, you have to replace anything that points to it, recursively. In a ptree, we’d need to know the subtree of the updated node and change all of them.

But btree fails pretty spectacularly:

Our web of pointers has meant we need to replace every single node in the tree! The extra circular pointers work to our detriment when looking for a persistent update.

What we’d like to do is somehow combine the ptree and the ctree more intelligently, so we don’t end up with a boat of extra pointers, but we still can find the children and the parent of a node.

Here, we make the critical simplifying assumption: we only care about efficient access of parents and children as well as updates of a single node. This is not actually a big deal in a world of immutable data structures: the only reason to have efficient updates on distinct nodes is to have a modification made by one code segment show up in another, and the point of immutability is to stop that spooky action at a distance.

So, on a single node, we want fast access to the parent and children and fast updates. Fast access means we need pointers going away from this node, fast updates means we need to eliminate pointers going into this node.

Easy! Just flip some pointers (shown in red.)

Congratulations, the data structure you see here is what we call a zipper! The only task left for us now is to figure out how we might actually encode this in a struct definition. In the process, we’ll assign some names to the various features inside this diagram.

Let’s consider a slightly more complicated example:

We’ve introduced a few more notational conveniences: triangles represent the tree attached to a given node when we don’t care about any of its subnodes. The squares are the values attached to any given node (we’ve shown them explicitly because the distinction between the node and its data is important.) The red node is the node we want to focus around, and we’ve already gone and flipped the necessary pointers (in red) to make everything else accessible.

When we’re at this location, we can either traverse the tree, or go up the red arrow pointed away from the green node; we’ll call the structure pointed to by this arrow a context. The combination of a tree and a context gives us a location in the zipper.

struct loc {

struct ctree *tree;

struct context *context;

}

The context, much like the tree, is a recursive data-structure. In the diagram below, it is precisely the node shaded in black. It’s not a normal node, though, since it’s missing one of its child pointers, and may contain a pointer to its own parent.

The particular one that this location contains is a “right context”, that is, the arrow leading to the context points to the right (shown in black in the following diagram).

As you can see, for our tree structure, a context contains another context, a tree, and a value.

Similarly, a “left context” corresponds to an arrow pointing to the left. It contains the same components, although it may not be quite obvious from the diagram here: where’s the recursive subcontext? Well, since we’re at the top of the tree, instead we have a “top context”, which doesn’t contain any values. It’s the moral equivalent of Nothing.

enum context_type {LEFT, RIGHT, TOP}

struct context {

enum context_type type;

// below only filled for LEFT and RIGHT

int val;

struct context *context;

struct ctree *tree;

}

And there we have it! All the pieces you need to make a zipper:

> data Tree a = Nil | Node a (Tree a) (Tree a)

> data Loc a = Loc (Tree a) (Context a)

> data Context a = Top

> | Left a (Tree a) (Context a)

> | Right a (Tree a) (Context a)

Exercises:

- Write functions to move up, down-left and down-right our definition of

Tree. - If we had the alternative tree definition

data Tree a = Leaf a | Branch Tree a) (Tree a), how would our context definition change? - Write the data and context types for a linked list.

Further reading: The original crystallization of this pattern can be found in Huet’s paper (PDF), and two canonical sources of introductory material are at Wikibooks and Haskell Wiki. From there, there is a fascinating discussion about how the differentiation of a type results in a zipper! See Conor’s paper (PDF), the Wikibooks article, and also Edward Kmett’s post on using generating functions to introduce more exotic datatypes to the discussion.

April 5, 2010zip: List<A>, List<B> -> List<(A, B)>

zip(Nil, Nil) = Nil

zip(_, Nil) = Nil

zip(Nil, _) = Nil

zip(Cons(a, as), Cons(b, bs)) = Cons((a, b), zip(as, bs))

fst: (A, B) -> A

fst((a, _)) = a

last: List<A> -> A

last(Cons(a, Nil)) = a

last(Cons(a, as)) = last(as)

foldl: (B, A -> B), B, List<A> -> B

foldl(_, z, Nil) = z

foldl(f, z, Cons(x, xs)) = foldl(f, f(z, x), xs)

Good grief Edward, what do you have there? It’s almost as if it were some bastardized hybrid of Haskell, Java and ML.

It actually is a psuedolanguage inspired by ML that was invented by Daniel Jackson. It is used by MIT course 6.005 to teach its students functional programming concepts. It doesn’t have a compiler or a formal specification (although I hear the TAs are frantically working on one as a type this), though the most salient points of its syntax are introduced in lecture 10 (PDF) when they start discussing how to build a SAT solver.

Our second problem set asks us to write some code in this pseudolanguage. Unfortunately, being a pseudolanguage, you can’t actually run it… and I hate writing code that I can’t run. But it certainly looks a lot like Haskell… just a bit more verbose, that’s all. I asked the course staff if I could submit the problem set in Haskell, and they told me, “No, since the course staff doesn’t know it. But if it’s as close to this language as you claim, you could always write it in Haskell and then translate it to this language when you’re done.”

So I did just that.

The plan wouldn’t really have been possible without the existence of an existing pretty printer for Haskell to do most of the scaffolding for me. From there, it was mucking about with <>, lparen and comma and friends in the appropriate functions for rendering data-types differently. Pretty printing combinators rock!

April 2, 2010I’m happy to report that I’ll be interning at Galois over the summer. I’m not quite sure how the name of the company passed into my consciousness, but at some point in January I decided it would be really cool to work at an all-Haskell shop, and began pestering Don Stewart (and Galois’s HR) for the next two months.

I’ll be working on some project within Cryptol; there were a few specific project ideas tossed around though it’s not clear if they’ll have already finished one of my projects by the time the summer rolls around. I’m also really looking forward to working in an environment with a much higher emphasis towards research, since I need to figure out if I’m going to start gunning for a PhD program at the end of my undergraduate program.

Hello, Portland! I can’t wait. :-)

March 31, 2010Code written by Anders Kaseorg.

In The Three Projections of Doctor Futamura, Dan Piponi treats non-programmers to an explanation to the Futamura projections, a series of mind-bending applications of partial evaluation. Go over and read it if you haven’t already; this post is intended as a spiritual successor to that one, in which we write some Haskell code.

The pictorial type of a mint. In the original post, Piponi drew out machines which took various coins, templates or other machines as inputs, and gave out coins or machines as outputs. Let’s rewrite the definition in something that looks a little bit more like a Haskell type.

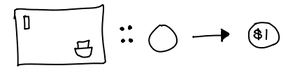

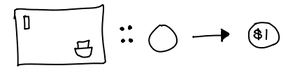

First, something simple: the very first machine that takes blank coins and mints new coins.

We’re now using an arrow to indicate an input-output relationship. In fact, this is just a function that takes blank coins as input, and outputs engraved coins. We can generalize this with the following type synonym:

> type Machine input output = input -> output

What about that let us input the description of the coin? Well, first we need a simple data type to represent this description:

> data Program input output = Program

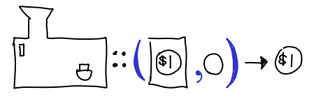

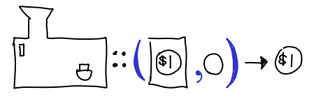

(Yeah, that data-type can’t really do anything interesting. We’re not actually going to be writing implementations for these machines.) From there, we have our next “type-ified’ picture of the interpreter:

Or, in code:

> type Interpreter input output = (Program input output, input) -> output

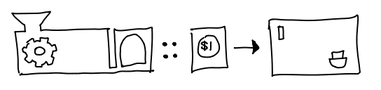

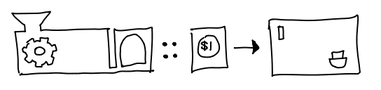

From there, it’s not a far fetch to see what the compiler looks like:

> type Compiler input output = Program input output -> Machine input output

I would like to remark that we could have fully written out this type, as such:

type Compiler input output = Program input output -> (input -> output)

We’ve purposely kept the unnecessary parentheses, since Haskell seductively suggests that you can treat a -> b -> c as a 2-ary function, when we’d like to keep it distinct from (a, b) -> c.

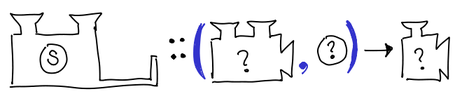

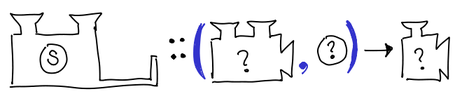

And at last, we have the specializer:

> type Specializer program input output =

> ((program, input) -> output, program) -> (input -> output)

We’ve named the variables in our Specializer type synonym suggestively, but program doesn’t just have to be Program: the whole point of the Futamura projections is that we can put different things there. The other interesting thing to note is that any given Specializer needs to be parametrized not just on the input and output, but the program it operates on. That means the concrete type that the Specializer assumes varies depending on what we actually let program be. It does not depend on the first argument of the specializer, which is forced by program, input and output to be (program, input) -> output.

Well, what are those concrete types? For this task, we can ask GHC.

To the fourth projection, and beyond! First, a few preliminaries. We’ve kept input and output fully general in our type synonyms, but we should actually fill them in with a concrete data type. Some more vacuous definitions:

> data In = In

> data Out = Out

>

> type P = Program In Out

> p :: P

> p = undefined

>

> type I = Interpreter In Out

> i :: I

> i = undefined

We don’t actually care how we implement our program or our interpreter, thus the undefined; given our vacuous data definitions, there do exist valid instances of these, but they don’t particularly increase insight.

> s :: Specializer program input output

> -- s (x, p) i = x (p, i)

> s = uncurry curry

We’ve treated the specializer a little differently: partial evaluation and partial application are very similar: in fact, to the outside user they do precisely the same thing, only partial evaluation ends up being faster because it is actually doing some work, rather than forming a closure, with the intermediate argument hanging around in limbo and not doing any useful work. However, we need to uncurry the curry, since Haskell functions are curried by default.

Now, the Futamura projections:

> type M = Machine In Out

> m :: M

> m = s1 (i, p)

Without the monomorphism restriction, s would have worked just as well, but we’re going to give s1 an explicit type shortly, and that would spoil the fun for the rest of the projections. (Actually, since we gave s an explicit type, the monomorphism restriction wouldn’t apply.)

So, what is the type of s1? It’s definitely not general: i and p are fully explicit, and Specializer doesn’t introduce any other polymorphic types. This should be pretty easy to tell, but we’ll ask GHC just in case:

Main> :t s1

s1 :: ((P, In) -> Out, P) -> In -> Out

Of course. It matches up with our variable names!

> type S1 = Specializer P In Out

> s1 :: S1

> s1 = s

Time for the second Futamura projection:

> type C = Compiler In Out

> c :: C

> c = s2 (s1, i)

Notice I’ve written s2 this time around. That’s because s1 (s1, i) doesn’t typecheck; if you do the unification you’ll see the concrete types don’t line up. So what’s the concrete type of s2? A little more head-scratching, and perhaps a quick glance at Piponi’s article will elucidate the answer:

> type S2 = Specializer I P M

> s2 :: S2

> s2 = s

The third Futamura projection, the interpreter-to-compiler machine:

> type IC = I -> C

> ic :: IC

> ic = s3 (s2, s1)

(You should verify that s2 (s2, s1) and s1 (s1, s2) and any permutation thereof doesn’t typecheck.) We’ve also managed to lose any direct grounding with the concrete:: there’s no p or i to be seen. But s2 and s1 are definitely concrete types, as we’ve shown earlier, and GHC can do the unification for us:

Main> :t s3

s3 :: ((S1, I) -> C, S1) -> I -> Program In Out -> In -> Out

In fact, it’s been so kind as to substitute some of the more gnarly types with the relevant type synonyms for our pleasure. If we add some more parentheses and take only the output:

I -> (Program In Out -> (In -> Out))

And there’s our interpreter-to-compiler machine!

> type S3 = Specializer S1 I C

> s3 :: S3

> s3 = s

But why stop there?

> s1ic :: S1 -> IC

> s1ic = s4 (s3, s2)

>

> type S4 = Specializer S2 S1 IC

> s4 :: S4

> s4 = s

Or even there?

> s2ic :: S2 -> (S1 -> IC)

> s2ic = s5 (s4, s3)

>

> type S5 = Specializer S3 S2 (S1 -> IC)

> s5 :: S5

> s5 = s

>

> s3ic :: S3 -> (S2 -> (S1 -> IC))

> s3ic = s6 (s5, s4)

>

> type S6 = Specializer S4 S3 (S2 -> (S1 -> IC))

> s6 :: S6

> s6 = s

And we could go on and on, constructing the nth projection using the specializers we used for the n-1 and n-2 projections.

This might seem like a big bunch of type-wankery. I don’t think it’s just that.

Implementors of partial evaluators care, because this represents a mechanism for composition of partial evaluators. S2 and S1 could be different kinds of specializers, with their own strengths and weaknesses. It also is a vivid demonstration of one philosophical challenge of the partial-evaluator writer: they need to write a single piece of code that can work on arbitrary n in Sn. Perhaps in practice it only needs to work well on low n, but the fact that it works at all is an impressive technical feat.

For disciples of partial application, this is something of a parlor trick:

*Main> :t s (s,s) s

s (s,s) s

:: ((program, input) -> output) -> program -> input -> output

*Main> :t s (s,s) s s

s (s,s) s s

:: ((input, input1) -> output) -> input -> input1 -> output

*Main> :t s (s,s) s s s

s (s,s) s s s

:: ((input, input1) -> output) -> input -> input1 -> output

*Main> :t s (s,s) s s s s

s (s,s) s s s s

:: ((input, input1) -> output) -> input -> input1 -> output

*Main> :t s (s,s) s s s s s

s (s,s) s s s s s

:: ((input, input1) -> output) -> input -> input1 -> output

But this is a useful parlor trick: somehow we’ve managed to make an arbitrarily variadic function! I’m sure this technique is being used somewhere in the wild, although as of writing I couldn’t find any examples of it (Text.Printf might, although it was tough to tell this apart from their typeclass trickery.)

March 29, 2010The fast, efficient association map has long been the holy grail of the functional programming community. If you wanted such an abstract data structure in an imperative language, there would be no question about it: you would use a hash table. But the fact that the hash table is founded upon the destructive update makes it hard to use with pure code.

What we are in search of is a strictly more powerful association map, one that implements a non-destructive update (i.e. is “persistent”). In the Haskell world, Data.Map is a reasonably compelling general-purpose structure that only requires the Ord typeclass on its keys. For keys that map cleanly on to machine-size integers, IntMap is an extremely fast purely functional that uses bit twiddling tricks on top of big-endian Patricia tries.

Other functional programming languages have championed their own datastructures: many of Clojure’s collections critical datastructures were invented by Phil Bagwell, among them the hash-array mapped trie (PDF), which drives Clojure’s persistent association maps.

On paper, the implementations have the following asymptotics:

- Data.Map. Let n and m be the number of elements in a map. O(log n) lookups, inserts, updates and deletes. O(n+m) unions, differences and intersections

- Data.IntMap. Let n and m be the number of elements in a map, and W be the number of bits in a machine-sized integer (e.g. 32 or 64). O(min(n,W)) lookups, inserts, updates and deletes. O(n+m) unions, differences and intersections.

- Hash array mapped trie. Let n be the number of elements in a map. Since Hickey’s implementation doesn’t have sub-tree pools or root-resizing, we’ll omit them from the asymptotics. O(log(n)) lookups, inserts, updates and deletes. No implementation for unions, differences and intersections is described.

Unfortunately, these numbers don’t actually tell us very much about the real world performance of these data structures, since the world of associations is competitive enough that the constant factors really count. So I constructed the following benchmark: generate N random numbers, and insert them into the map. Then, perform lookups on N/2 of those random numbers, and N/2 other numbers that were not used (which would constitute misses). The contenders were IntMap and HAMT (with an implementation in Java and an implementation in Haskell). Initial results indicated that IntMap was faster than Java HAMT was much faster than Haskell HAMT.

Of course, this was absolutely bogus.

I turned to the Clojure mailing list and presented them with a strange (incorrect) result: Haskell’s IntMap was doing up to five times better than Clojure’s built-in implementation of HAMT. Rich Hickey immediately pointed out three problems with my methodology:

- I was using Java’s default heap size (to be fair, I was using Haskell’s default heap size too),

- It wasn’t performed with the

-server flag, and - I wasn’t accounting for the JVM’s profile-driven optimization.

(There were a few more comments about random number generation and interleaving, but further testing revealed those to be of negligible cost.) Rich offered me some new code that used (apply hash-map list-of-vals) to construct the hash-map, and after fixing a bug where Rich was only inserting N/2 entries into the hash table, I sallied on.

With an improved set of test-cases, I then derived the following statistics (for the source, check out this IntMap criterion harness, and the postscript of this blog post for the Clojure harness):

IntMap Java HAMT (32K-512K) Java HAMT (512K-32K)

32K .035s .100s .042s

64K .085s .077s .088s

128K .190s .173s .166s

256K .439s .376s .483s

512K 1.047s 1.107s 1.113s

Still puzzling, however, was the abysmal performance of my Haskell reimplementation of HAMT, performing three to four times worse even after I tore my hair out with bit twiddling tricks and GHC boxing and unboxing. Then, I had a revelation:

public static PersistentHashMap create(List init){

ITransientMap ret = EMPTY.asTransient();

for(Iterator i = init.iterator(); i.hasNext();)

{

Object key = i.next();

if(!i.hasNext())

throw new IllegalArgumentException(String.format("No value supplied for key: %s", key));

Object val = i.next();

ret = ret.assoc(key, val);

}

return (PersistentHashMap) ret.persistent();

}

}

That tricky Hickey: he’s using mutation (note the asTransient call) under the hood to optimize the (apply hash-map ...) call! A few tweaks later to force use of the functional interface, and voila:

Haskell Clojure

128K 0.56s 0.33s

256K 1.20s 0.84s

512K 2.62s 2.80s

Much more comparable performance (and if you watch closely the JVM numbers, they start off at about the same as Haskell’s, and then speed up as HotSpot kicks in.)

Unfortunately, I can’t play similar tricks in the Haskell world. For one thing, GHC doesn’t have runtime profile-based optimization. Additionally, while I certainly can unsafely freeze a single array in GHC (this is standard operating procedure in many packages), I can’t recursively freeze arrays pointing to arrays without walking the entire structure. Thus, blazing fast construction of recursive datastructures with mutation remains out of reach for Haskell… for now.

This is very much a story in progress. In particular, I still have to:

- Do a much more nuanced benchmark, which distinguishes the cost of insertion, lookup and other operations; and

- Implement IntMap in Java and see what the JVM buys the algorithm, unifying the garbage collection strategies would also be enlightening.

Postscript. You can see the gory details of the benchmarking on the Clojure mailing list. Here is the test code that was used to test Java’s HAMT implementation.

First with mutation:

(ns maptest (:gen-class))

(defn mk-random-stream []

(let [r (new ec.util.MersenneTwisterFast)]

(repeatedly (fn [] (. r (nextInt))))))

(defn main [i]

(let [vals (vec (take (* i 2) (mk-random-stream)))

dvals (take (* i 2) (doall (interleave vals vals)))]

(dotimes [_ 10]

(time

(let [m (apply hash-map dvals)]

(reduce (fn [s k] (+ s (m k 0)))

0

(take i (drop (/ i 2) vals))))))))

(doseq [n (range 5 10)]

(let [i (* 1000 (int (Math/pow 2 n)))]

(println " I = " i)

(main i)))

Here is the alternative main definition that forces usage of the functional interface:

(defn main [i]

(let [vals (vec (take (* i 2) (mk-random-stream)))]

(dotimes [_ 10]

(time

(let [m (reduce (fn [m x] (assoc m x x)) (hash-map) vals)]

(reduce (fn [s k] (+ s (m k 0)))

0

(take i (drop (/ i 2) vals))))))))

March 24, 2010Hello from Montreal! I’m writing this from a wireless connection up on the thirty-ninth floor of La Cité. Unfortunately, when we reading the lease, the only thing we checked was that it had “Internet”… not “Wireless.” So what’s a troop of MIT students with an arsenal of laptops and no wireless router to do? Set up wireless ad hoc networking.

Except it doesn’t actually work. Mostly. It took us a bit of fiddling and attempts on multiple laptops to finally find a configuration that worked. First, the ones that didn’t work:

- Windows, as Daniel Gray tells me, has two standard methods for creating ad hoc networks: bridging two networks or …. We tried both of them, and with … we were able to connect other Windows laptops and Mac OS X laptops… but no luck with the Linux laptops. As three of us are Linux users, we were quite unhappy with this state of affairs.

- Linux theoretically has support for ad hoc networks using dnsmasq; however, we tried two separate laptops and neither of them were able to set up an ad hoc network that any of the other laptops were able to use. We did discover some hilarious uninitialized field bugs for ESSIDs.

- Mac OS X. At this point, we were seriously considering going out, finding a wireless hardware store, and buying a router for the apartment. However, someone realized that there was one operating system we hadn’t tried yet. A few minutes of fiddling… and yes! Ad hoc network that worked on all three operating systems!

Ending score: Apple +1, Microsoft 0, Linux -1. Although, it’s hard to be surprised that no one actually is paying the attention necessary to the wireless drivers.

March 22, 2010Abstraction (n.) The act or process of separating in thought, of considering a thing independently of its associations; or a substance independently of its attributes; or an attribute or quality independently of the substance to which it belongs. (Oxford English Dictionary)

Abstraction is one of the most powerful beasts in the landscape of programming, but it is also one of the most elusive to capture. The places where abstraction may be found are many:

- Good artists copy. Great artists steal. Abstractions that other people have (re)discovered, (re)used and (re)implemented are by far the easiest to find.

- First time you do something, just do it. Second time, wince at duplication. Third time, you refactor. Refactoring introduces small pieces of ad hoc abstraction. The quality varies though: the result might be something deeper, but it might just be mundane code reuse.

- Grow your framework. A lengthy process where you build the abstraction and the application, build another distinct application on the abstraction, and reconcile. This takes a lot of time, and is entirely dependent on people’s willingness to break BC and make sweeping changes.

- Give the problem to a really smart person. Design is a creative process, design by committee results in moldy code. A single person unifies the abstraction and picks the battles to fight when an abstraction needs to change.

- Turn to nature. User interfaces often introduce a form of abstraction, and it’s common to turn to real life and see what’s there. Note that there are really good abstractions that don’t exist in real-life: the concept of undo is positively ridiculous in the real world, but probably one of the best inventions in computers.

I’d like to propose one other place to turn when you’re hunting for abstractions: pure mathematics.

“Pure mathematics?”

Yes, pure mathematics. Not applied mathematics, which easily finds its place in a programmers toolbox for tackling specific classes of problems.

“Ok, mathematicians may do neat things… but they’re too theoretical for my taste.”

But that’s precisely what we’re looking for! Pure mathematics is all about manipulating abstract objects and deductively proving properties about them. The mathematicians aren’t talking about a different kind of abstraction, they’re just starting off from different concrete objects than a programmer might be. The mathematicians have just have been doing it much longer than programmers (set the mark at about 600BC with the Greeks.) Over this period of time, mathematicians have gotten pretty damn good at creating abstractions, handling abstractions, deducing properties of abstractions, finding relationships between abstractions, and so forth. In fact, they’re so good that advanced mathematics has a reputation for abstracting concepts way beyond what any “normal” person would tolerate: Lewis Carroll is one prominent figure known for satirizing what he saw as ridiculous ideas in mid-19th century mathematics.

Of course, you can’t take an arbitrary mathematical concept and attempt to shoehorn it into your favorite programming language. The very first step is looking at some abstract object and looking for concrete instances of that object that programmers care about. Even structures that have obvious concrete instances have more subtle instances that are just as useful.

It is also the case that many powerful mathematical abstractions are also unintuitive. Programmers naturally shy away from unintuitive ideas: it is an example of being overly clever. The question of what is intuitive has shaped discussions in mathematics as well: when computability theory was being developed, there were many competing models of computation vying for computer scientists’ attentions. Alonzo Church formulated lambda calculus, a highly symbolic and abstract notion of computation; Alan Turing formulated Turing machines, a very physical and concrete notion of computation. In pedagogy, Turing machines won out: open any introductory computability textbook (in my case, Sipser’s textbook) and you will only see the Turing machines treated to the classic proofs regarding the undecidability of halting problems. The Turing machine is much simpler to understand; it maps more cleanly to the mental model of a mathematician furiously scribbling away a computation.

But no computer scientist (and certainly not Alonzo Church) would claim that Turing machines are the only useful model to study. Lambda calculus is elegant; after you’ve wrapped your head around it, you can express ideas and operations concisely which, with Turing machines, would have involved mucking around with encodings and sweeping the head around and a lot of bookkeeping. Writing Turing machines, put bluntly, is a pain in the ass.

I now present two examples of good ideas in mathematics resulting in good ideas in programming.

The first involves the genesis of Lisp. As Sussman tells me, Lisp was originally created so that McCarthy could prove Gödel’s incompleteness theorem without having to resort to number theory. (McCarthy is quoted as saying something a little weaker: Lisp was a “way of describing computable functions much neater than the Turing machines or the general recursive definitions used in recursive function theory.”) Instead of taking the statement “this statement cannot be proven” and rigorously encoding in a stiff mathematical formalism, it could simply be described in Lisp (PDF). Thus, its original formulation featured m-expressions, which looked a little like function[arg1 arg2] and represented the actual machine, as opposed to the s-expression which was the symbolic representation. It wasn’t until later that a few graduate students thought, “Hm, this would actually be a useful programming language,” and set about to actually implement Lisp. Through Gödel’s incompleteness theorem, the powerful notion of code as data was born: no other language at the time had been thinking about programs in this way.

The second is the success of Category Theory in Haskell. The canonical example is monads, the mathematical innovation that made input/output in lazy languages not suck (although a mathematical friend of mine tells me monads are not actually interesting because they’re not general enough.) But the ideas behind the functor and applicative functor encapsulate patterns pervasive in all programming languages. An example of a reformulation of this concept can be seen in numpy’s universal functions. They don’t call it a functor, instead they use terms such as “broadcasting” and “casting” and discuss the need to use special universal versions of functions on numpy arrays to get element-by-element operations. The interface is usable enough, but it lacks the simplicity, elegance and consistency that you get from actually realizing, “Hey, that’s just a functor…”

Those mathematicians, they’re smart folk. Perhaps we programmers could learn a thing or two from them.

Postscript. Thanks to Daniel Kane for answering my impromptu question “What is mathematics about?” and suggesting a few of the examples of mathematics leaking back into computer engineering.

March 19, 2010Python is a language that gives you a lot of rope, in particular any particular encapsulation scheme is only weakly enforced and can be worked around by a sufficiently savvy hacker. I fall into the “my compiler should stop me from doing stupid things” camp, but I’ll certainly say, dynamic capabilities sure are convenient. But here’s the rub: the language must show you where you have done something stupid.

In this case, we’d like to see when you have improperly gone and mutated some internal state. You might scoff and say, “well, I know when I change my state”, but this is certainly not the case when you’re debugging an interaction between two third party libraries that you did not write. Specifically I should be able to point at a variable (it might be a local variable, a global variable, or a class/instance attribute) and say to Python, “tell me when this variable changes.” When the variable changes, Python should tell me who changed the variable (via a backtrace) and what the variable changed to. I should be able to say, “tell me when this variable changed to this value.”

Well, here is a small module that does just that: mutsleuth. Import this module and install the watcher by passing mutsleuth.watch an expression that evaluates to the variable you’d like to check.

Here’s an example: suppose I have the following files:

good.py:

b = "default value"

evil.py:

import good

good.b = "monkey patch monkey patch ha ha ha"

test.py:

import mutsleuth

mutsleuth.watch("good.b")

import good

import evil

When you run test.py, you’ll get the following trace:

ezyang@javelin:~/Dev/mutsleuth$ python test.py

Initialized by:

File "test.py", line 5, in <module>

import evil

File "/home/ezyang/Dev/mutsleuth/good.py", line 1, in <module>

b = "good default value"

Replaced by:

File "test.py", line 5, in <module>

import evil

File "/home/ezyang/Dev/mutsleuth/evil.py", line 2, in <module>

good.b = "monkey patch monkey patch ha ha ha"

There are a few caveats:

- Tracing doesn’t start until you enter another local scope, whether by calling a function or importing a module. For most larger applications, you will invariably get this scope, but for one-off scripts this may not be the case.

- In order to keep performance tolerable, we only do a shallow comparison between instances, so you’ll need to specifically zoom in on a value to get real mutation information about it.

Bug reports, suggestions and improvements appreciated! I went and tested this by digging up an old bug that I would have loved to have had this module for (it involved logging code being initialized twice by two different sites) and verified it worked, but I haven’t tested it “cold” yet.

Hat tip to Bengt Richter for suggesting this tracing originally.