June 21, 2010I’ve had a rather successful tenure with autogenerated documentation, both as a writer and a reader. So when Jacob Kaplan Moss’s articles on writing “great documentation” resurfaced on Reddit and had some harsh words about auto-generated documentation, I sat back a moment and thought about why autogenerated documentation leave developers with a bad taste in their mouths.

I interpreted Moss’s specific objections (besides asserting that they were “worthless” as the following:

- They usually didn’t contain the information you were looking for (“At best it’s a slightly improved version of simply browsing through the source”),

- They were verbose (“good for is filling printed pages when contracts dictate delivery of a certain number of pages of documentation”),

- The writers skipped the “writing” part (“There’s no substitute for documentation written…”),

- The writers skipped the “organizing” part (“…organized…”),

- The writers skipped the “editing” part (“…and edited by hand.”),

- It gave the illusion of having documentation (“…it lets maintainers fool themselves into thinking they have documentation”).

Thus, the secret to successful autogenerated docs is:

No doubt, gentle reader, you are lifting your eyebrow at me, thinking to yourself, “Of course you should remember your audience; that’s what they always teach you in any writing class. You haven’t told us anything useful!” So, let me elaborate.

Why do developers forget to “remember their audience”? A defining characteristic of autogenerated documentation is that the medium it is derived from is source code: lines of programming language and docblocks interleaved together. This has certain benefits: for one, keeping the comments close to the code they describe helps ward off documentation rot as code changes, additionally, source divers have easy access to documentation pertinent to a source file they are reading. But documentation is frequently oriented towards people who are not interested in reading the codebase, and thus the act of writing code and documentation at the same time puts the writer into the wrong mindset. Compare this with sitting down to a tutorial, the text flowing into an empty document unprejudiced by such petty concerns as code.

This is a shame, because in the case of end-user developer documentation (really the only appropriate time for autodocs), the person who originally wrote the code is most likely to have the relevant knowledge to share about the interface being documented.

What does it mean to “remember my audience”? Concisely, it’s putting yourself into your end-user’s shoes and asking yourself, “If I wanted to find out information about this API, what would I be looking for?” This can be hard (and unfortunately, there are no secrets here), but the first step is to be thinking about it at all.

How can I remember to consider the audience when writing docblocks? While it would be nice if I could just snap my fingers and say, “I’m going to write docblocks with my audience in mind,” I know that I’m going to forget and write a snippy docblock because I was in a rush one day or omit the docblock entirely and forget about it. Writing documentation immediately after the code is written can be frustrating if five minutes later you decide that function did the wrong thing and needs to be axed.

Thus, I’ve set up these two rules for myself:

It’s OK not to write documentation immediately after writing code (better not yet than poorly).

Like many people working in high-level languages, I like using code to prototype API designs. I’ll write something, try to use it, change it to fit my use-case, write some more, and eventually I’ll have both working code and a working design. If I don’t write documentation while I’m prototyping, that’s fine, but when that’s all over I need to write the documentation (hopefully before the code slips out of my active mindspace.) The act of writing the documentation at the end helps finalize the API, and can suggest finishing touches. I also use my toolchain to tell me when I’ve left code undocumented (with Sphinx, this is using the coverage plugin).

When writing documentation, constantly look at the output the end-user will see.

You probably have a write/preview authoring cycle when you edit any sort of text that contains formatting. This cycle should carry over to docblocks: you edit your docblock, run your documentation build script, and inspect the results in your browser. It helps if the output you’re producing is beautiful! It also means that your documentation toolchain should be smart about what it needs to recompile when you make changes. The act of inspecting what a live user will see helps put you in the right mindset, and also force you to say, “Yeah, these docs are not actually acceptable.”

My autodocumentor produces verbose and unorganized output! I’ve generally found autogenerated documentation from Python or Haskell to be much more pleasant to read than that from Java or C++. The key difference between these languages is that Python and Haskell organize their modules into files; thus, programmers in those language find it easier to remember the module docblock!

The module docblock is one of great import. If your code is well-written and well-named, a competent source-diver can usually figure out what a particular function does in only a few times longer than it would take for them to read your docblock. The module is the first organizational unit above class and function, precisely where documentation starts becoming the most useful. It is the first form of “high-level documentation” that developers pine for.

So, in Python and Haskell, you write all of the functionality involved in a module in a file, and you can stick a docblock up top that says what the entire file does. Easy! But in Java and C++, each file is a class (frequently a small one), so you don’t get a chance to do that. Java and recent C++ have namespaces, which can play a similar role, but where are you supposed to put the docblock for what in Java is effectively a directory?

There is also substantial verbosity pollution that comes from an autodocumenting tool attempting to generate documentation for classes and functions that were intended to not be used by the end-user. Haddock (Haskell autodocumentor) strongly enforces this by not generating documentation for any function that the module doesn’t export. Sphinx (Python autodocumentor) will ignore by default functions prefixed with an underscore. People documenting Java, which tends to need a lot of classes, should think carefully about which classes they actually want people to use.

Final thoughts. The word “autogenerated documentation” is a misnomer: there is no automatic generation of documentation. Rather, the autodocumentor should be treated as a valuable documentation building tool that lets you get the benefits of cohesive code and comments, as well as formatting, interlinking and more.

June 18, 2010This is part three of a six part tutorial series on c2hs. Today, we take a step back from the nitty gritty details of FFI bindings and talk about more general design principles for your library.

On the one hand, writing an FFI binding can little more than churning out the glue code to let you write “C in Haskell,” the API of your library left at the whimsy of the original library author. On the other hand, you can aspire to make your interface indistinguishable from what someone might have written in pure Haskell, introducing modest innovation of your own to encode informally documented invariants from the C code into the type system.

Overall design. Larger bindings benefit from being divided into two layers: a low-level binding and a higher-level user-friendly binding. There is a large amount of code necessary to make C functions available to call by Haskell, and the obvious thing to do with it is to stow it away in its own namespace, frequently with Internal somewhere in the name.

Low-level design. In the low-level binding, you should organize your foreign imports the way the C header files were organized. Keep the names similar. While it won’t be possible to have identical C function names and Haskell function names—C functions are allowed to begin with capital letters and Haskell functions are not (there is an opposite situation for types and data constructors)—you can still adopt a consistent transformation. c2hs, by default, converts Foo_BarBaz in C to fooBarBaz; that is, words after underscores are capitalized, the first letter is uncapitalized, and underscores are removed.

There is room to improve upon the original API, however. The rule of thumb is, if you can make a non-invasive/local change that improves safety or usability, do it. These include:

- Marshalling vanilla C values (e.g.

int, float and even char*, if it’s a null terminated string) into their natural Haskell forms (Int, Float and String). Care should be taken, as the native Haskell types lose precision to their C counterparts, and thus should ensure that the application doesn’t need to squeeze out every last higher bit (e.g. with a bit field). 80% of the time, a lossy transformation is acceptable, - Converting

int into Bool from some naming convention (perhaps boolean values are prefixed with f for flag), - Putting

malloc’d pointers into memory management with foreign pointers. This advice is worth repeating: Haskell has memory management, and it would be criminal not to use it as soon as possible. Plus, you don’t have to write an explicit Haskell deallocation function. - Converting functions that initialize some memory space (

set_struct_default) into pure versions (structDefault) with unsafePerformIO, alloca and peek. Note that you should do this in conjunction with the appropriate Storable instance to marshal the C struct into a persistent Haskell datatype. - Marshalling more complex C values (arrays, mostly) into Haskell lists, assuming that bounds information is consistent and available locally.

We will discuss these techniques in more detail in the coming posts, since this is precisely where c2hs is used the most.

It’s useful to know when not to simplify: certain types of libraries may have highly efficient in-memory representations for large structures; marshalling them to and from Haskell is wasteful. Poorly written C code may also you hand you arrays for which you cannot find easily their length; deferring their marshalling to the higher-level interface may be a better idea. Decide which structures you are explicitly not going to marshal and enforce this across the board. My preference is to marshal flat structs that contain no pointers, and leave everything else be.

High-level design. While there are certainly exotic computational strcutures like arrows, applicative functors and comonads which can be useful in certain domains, we will restrict our discussion to the go-to tools of the Haskell programmer: pure functions and monads.

Pure functions. Transforming the mutable substrate that C is built upon into the more precious stuff of pure functions and persistent data structures is a tricky task, rife with unsafePerformIO. In particular, just because a C function published purpose seems to not involve mutating anything, it may perform some shared state change or rebalance the input datastructure or printf on failure, and you have to account for it. Unless your documentation is extremely good, you will need to do source diving to manually verify invariants.

There will be some number of functions that are referentially transparent; these are a precious commodity and can be transformed into pure functions with ease. From there, you will need to make decisions about how a library can and cannot be used. A set of internal state transformation functions may not be amenable to a pure treatment, but perhaps a function that orchestrates them together leaks no shared state. Data structures that were intended to be mutated can be translated into immutable Haskell versions, or frozen by your API, which exposes no method of mutating them (well, no method not prefixed by unsafe) to the end user.

Monads. First an obvious choice: are you going to chuck all of your functions into the IO monad, or give the user a more restrictive monad stack that performs IO under the hood, but only lets the user perform operations relevant to your library. (This is not difficult to do: you newtype your monad stack and simply fail to export the constructor and omit the MonadIO instance.) :

newtype MyMonad a = MyMonad { unMyMonad :: ReaderT Env IO a }

deriving (MonadReader Env, Monad, Functor)

You will be frequently passing around hidden state in the form of pointers. These should be wrapped in newtypes and not exposed to the end-user. Sometimes, these will be pointers to pointers, in the case of libraries that have parameters **ppFoo, which take your pointer and rewrite it to point somewhere else, subsuming the original object. :

newtype OpaqueStruct = OpaqueStruct { unOpaqueStruct :: ForeignPtr (Ptr CStruct) }

Shared state means that thread safety also comes into play. Haskell is an incredibly thread friendly language, and it’s easy, as a user of a library, to assume that any given library is thread-safe. This is an admirable goal for any library writer to strive for, but one made much harder by your dependence on a C-based library. Fortunately, Haskell provides primitives that make thread safety much easier, in particular MVar, TVar and TMVar; simply store your pointer in this shared variable and don’t let anyone else have the pointer. Extra care is necessary for complex pointer graphs; be sure that if you have an MVar representing a lock for some shared state, there isn’t a pointer squirreled away elsewhere that some other C code will just use. And of course, if you have persistent structures, maintaining consistency is trivial. :

withMVar (unOpaqueStruct o) $ \o_ ->

withForeignPtr o_ $ \p ->

-- peek ’n poke the piggy, erm, pointer

One particularly good technique for preventing end-users from smuggling pointers out of your beautiful thread-safe sections is the application of a rank-2 type, akin to the ST monad. The basic premise is that you write a function with the type (forall s. m s a) -> a. The forall constraint on the argument to this function requires the result a to not contain s anywhere in its type (for the more technically inclined, the forall is a statement that I should be able to place any s in the statement and have it be valid. If some specific s' was in a, it would be only valid if I set my s to that s', and no other s). Thus, you simply add a phantom type variable s to any datatype you don’t want smuggled out of your monad, and the type system will do the rest. Monadic regions builds on this basic concept, giving it composability (region polymorphism). :

newtype LockedMonad i a = LockedMonad { unLockedMonad :: ReaderT Env IO a }

deriving (MonadReader Env, Monad, Functor)

runLockedMonad :: (forall i. LockedMonad i a) -> IO a

runLockedMonad m = runReaderT (unLockedMonad m) =<< newEnv

data LockedData i a = LockedData a

We will not be discussing these ideas as part of c2hs; use of the preprocessor is mostly distinct from this part of the design process. However, it is quite an interesting topic in its own right!

Next time. First steps in c2hs

June 16, 2010Last Tuesday, Eric Mertens gave the Galois tech talk Introducing Well-Founded Recursion. I have to admit, most of this went over my head the first time I heard it. Here are some notes that I ended up writing for myself as I stepped through the code again. I suggest reading the slides first to get a feel for the presentation. These notes are oriented towards a Haskell programmer who feels comfortable with the type system, but not Curry-Howard comfortable with the type system.

> module Quicksort where

>

> open import Data.Nat public using (ℕ; suc; zero)

> open import Data.List public using (List; _∷_; []; _++_; [_]; length; partition)

> open import Data.Bool public using (Bool; true; false)

> open import Data.Product public using (_×_; _,_; proj₁; proj₂)

Agda is a proof assistant based on intuitionistic type theory; that is, the Curry-Howard isomorphism. The Curry-Howard isomorphism states that things that look like types and data can also be treated as propositions and proofs, and one of the keys to understanding well-founded recursion in Agda is to freely interchange between the two, because we will use the type system as a way of making propositions about our code, which Agda will use when checking it. We’ll try to present both perspectives of the types and propositions.

Types : Data :: Propositions : Proofs

Agda needs to be convinced that your proof works: in particular, Agda wants to know if you’ve covered all the cases (exhaustive pattern matching, totality) and if you aren’t going to procrastinate on the answer (termination). Agda is very clever when it comes to case checking: if it knows that a case couldn’t be fulfilled in practice, because its type represents a falsehood, it will not ask you to fill it out. However, the termination checker frequently needs help, which is where well-founded recursion comes in.

Warmups.

Our first data type today is top: the type inhabited by precisely one value, unit. This is () in Haskell. Data inhabits a type the way a proof exists for a proposition; you can think of a type as a “house” in which there reside any number of inhabitants, the data types. Frequently infinitely many. You’ll see Set pop a lot: rigorously, it’s the type of “small” types, with Set₁ being larger, Set₂ larger still, and so forth…

> data ⊤ : Set where unit : ⊤

Bottom is the type inhabited by nothing at all. If no proof exists for the proposition, it is false! In the same way, the top proposition is vacuously true, since we said so! At the value level, this is undefined or error “foobar” in Haskell; at the type level, it’s be called Void, though no one actually uses that in real code. In Agda, these are one and the same.

> data ⊥ : Set where

We pulled in natural numbers from Data.Nat, but here’s what a minimal definition would look like:

data ℕ : Set where

zero : ℕ

suc : ℕ → ℕ

It is worth dwelling that Agda numeric constants such as 0 or 2 are syntax sugar for zero and suc (suc zero). They also may show up in types, since Agda is dependently typed. (In Haskell, you’d have to push the definition of natural numbers into the type system; here we can write a normal data definition and then lift them up automatically. Power to the working class!)

This function does something very strange:

> Rel : Set → Set₁

> Rel A = A → A → Set

In fact, it is equivalent to this expanded version:

Rel A = (_ : A) → (_ : A) → (_ : Set)

So the resulting type is not A → A → Set, but rather, it is something whose type is A, something else whose type is A, and as a result something whose type is Set. In Haskell terms, this is not a type function of kind * → *; this is more like an illegal * -> (a -> a -> *).

Here is an example of a simple relation: less-than for natural numbers. :

> data _<_ (m : ℕ) : ℕ → Set where

> <-base : m < suc m

> <-step : {n : ℕ} → m < n → m < suc n

Not so simple Agda syntax:

- The (m : ℕ) indicates that _<_ is parametrized by m, making m, a value of type ℕ, available throughout our data constructors. Parametrization means it is also required to be the first argument of _<_; at this point, you should check all of the type signatures of the constructors and see that they really are of form m<_

- The {n : ℕ} indicates an “implicit” parameter, which means when we go to invoke <-step, we don’t need to pass it; Agda will automatically figure it out from a later argument, in this case, m < n.

- Remember that “for all x : A, y : B”, is the same as providing a total function f(x : A) : B. So there’s a convenient shorthand ∀ x → which is equivalent to (x : _) → (the underscore means any type is ok.)

With the syntax out of the way, the mathematical intent of this expression should be clear: for any number, we automatically get a proof m<m+1; and with m<n → m<n+1, we can inductively get the rest of the proofs. If you squint, you can also see what is meant in terms of data: <-base is a nullary constructor, whereas <-step is a recursive constructor.

Let’s prove that 3 < 5. We start off with <-base : 3 < 4 (how did we know we should start there and not with 4 < 5? Notice that m, our parameter, is 3: this is a hint that all of our types will be parametrized by 3.) Apply step once: 3 < suc 4 = 3 < 5, QED. :

> example₁ : 3 < 5

> example₁ = <-step <-base

Recall that true propositions are inhabited by data types, whereas false propositions are not. How can we invert them? In logic, we could say, “Suppose that the proposition was the case; derive a contradiction.” In types, we use the empty function: the function that has no domain, and thus while existing happily, can’t take any inputs. A function has no domain only if it’s input type is not inhabited, so the only way we can avoid having to give a contradiction is to… not let them ask the question in the first place! :

> _≮_ : Rel ℕ

> a ≮ b = a < b → ⊥

() denotes falsity, in this case () : 5 < 0, which clearly can never be true, since <-base doesn’t pattern match against it (suc m != 0). A point worth mentioning is that Agda requires your programs to be complete, but doesn’t ask you to pattern match against absurdities. :

> example₂ : 5 ≮ 2

> example₂ (<-step (<-step ()))

Well-foundedness.

We introduce a little Agda notation; modules let us parametrize over some variable over an extended block then just the constructors of a ‘data’ declaration. Members of a module can be accessed ala WF.Well-founded A (rest of the arguments). This is quite convenient and idiomatic, though not strictly necessary; we could have just parametrized all of the members accordingly. We also happen to be parametrizing over a type. :

> module WF {A : Set} (_<_ : Rel A) where

Logically, what it means for an element to be accessible is that for all y such that y < x, y is accessible. From a data and logic view, it states if you want me to give you Acc x, the data/proof you want, you’ll have to give me a proof that for all y, if you give me a proof that y < x, I can determine Acc y. Now that we’re trying to prove properties about our types and functions, treating our data types as strictly data is making less and less sense. :

> data Acc (x : A) : Set where

> acc : (∀ y → y < x → Acc y) → Acc x

The entire type A is well-founded if all elements in it are accessible. Alternatively, the entire type A is well-founded if, given an element in it, I can produce an accessibility proof for that element. Note that its type is Set; this a type, the proposition I want to prove! :

> Well-founded : Set

> Well-founded = ∀ x → Acc x

Proof for well-foundedness on naturals related by less-than. :

> <-ℕ-wf : WF.Well-founded _<_

> <-ℕ-wf x = WF.acc (aux x)

> where

> aux : ∀ x y → y < x → WF.Acc _<_ y

> -- : (x : _) → (∀ y → y < x → WF.Acc _<_ y)

> aux .(suc y) y <-base = <-ℕ-wf y

Base case, (e.g. x=5, y=4). This, conveniently enough, triggers the well-founded structural recursion on ℕ by checking if y is well-founded now. :

> aux .(suc x) y (<-step {x} y<x) = aux x y y<x

The structural recursion here is on _<_; we are peeling back the layers of <-step until y<x = <-base, as might be the case for 3<4 (but not 3<6). We’re essentially appealing to a weaker proof that is still sufficient to prove what we’re interested in. Notice that we are also recursing on x; actually, whatever we know about x, we knew from y<x (less information content!), so we indicate that with a dot. Eventually, x will be small enough that y is not much smaller than x (<-base).

Where do we deal with zero? Consider aux zero : ∀ y -> y < zero → WF.Acc _<_ y. This is the empty function, since y < zero = ⊥ (no ℕ is less than zero!) In fact, this is how we get away with not writing cases for yx (the upper triangle): it’s equivalent to y≮x which are all bottom, and give us empty functions for free.

In fact, there is a double-structural recursion going on here, one x, and one on y<x. The structural recursion on x is on just aux, but once we conclude <-base, we do a different structural recursion on y with <-ℕ-wf. This fills out the bottom right triangle on the xy-plane split by y=x-1; the upper left triangle is not interesting, since it’s just a barren wasteland of bottom.

Standard mathematical trick: if you can reduce your problem into another that you’ve already solved, you solved your problem! :

> module Inverse-image-Well-founded { A B }

> -- Should actually used ≺, but I decided it looked to similar to < for comfort.

> (_<_ : Rel B)(f : A → B) where

> _⊰_ : Rel A

> x ⊰ y = f x < f y

>

> ii-acc : ∀ {x} → WF.Acc _<_ (f x) → WF.Acc _⊰_ x

> ii-acc (WF.acc g) = WF.acc (λ y fy<fx → ii-acc (g (f y) fy<fx))

The types have to look right, so we unwrap our old proof g and wrap it into a new lambda, pushing the reduction via f into our proof (i.e. WF.acc data constructor). :

> ii-wf : WF.Well-founded _<_ → WF.Well-founded _⊰_

> ii-wf wf x = ii-acc (wf (f x))

> -- wf = λ x → ii-acc (wf (f x))

> -- I.e. of course the construction ii-acc will work for any x.

Here, we finally use our machinery to prove that lists, compared with their lengths, are well-founded. :

> module <-on-length-Well-founded { A } where

> open Inverse-image-Well-founded { List A } _<_ length public

> wf : WF.Well-founded _⊰_

> wf = ii-wf <-ℕ-wf

A little bit of scaffolding code that does not actually “change” the proof, but changes the propositions. We’ll need this for the PartitionLemma. :

> s<s : ∀ {a b} → a < b → suc a < suc b

> s<s <-base = <-base

> s<s (<-step y) = <-step (s<s y)

Show that partitioning a list doesn’t increase its size. :

> module PartitionLemma { A } where

> _≼_ : Rel (List A)

> x ≼ y = length x < suc (length y) -- succ to let us reuse <

For all predicates and lists, each partition’s length is less than or equal to the original length of the list. proj₁ and proj₂ are Haskell fst and snd. :

> partition-size : (p : A → Bool) (xs : List A)

> → proj₁ (partition p xs) ≼ xs

> × proj₂ (partition p xs) ≼ xs

Though we’ve expressed our proposition in terms of ≼, we still use the original < constructor. <-base actually means equality, in this context! :

> partition-size p [] = <-base , <-base

> partition-size p (x ∷ xs)

> with p x | partition p xs | partition-size p xs

> ... | true | as , bs | as-size , bs-size = s<s as-size , <-step bs-size

> ... | false | as , bs | as-size , bs-size = <-step as-size , s<s bs-size

And finally, Quicksort. :

> module Quick {A} (p : A → A → Bool) where

Open the presents (proofs). :

> open <-on-length-Well-founded

> open PartitionLemma

> quicksort' : (xs : List A) → WF.Acc _⊰_ xs → List A

> quicksort' [] _ = []

> quicksort' (x ∷ xs) (WF.acc g) ::

From the partition lemma, we get small ≼ xs and big ≼ xs. By making length well-founded, we are now able to “glue” together the layer of indirection: x ∷ xs originally was strictly smallers and structurally recursive, and the partition lemma lets us say to the termination checker that small, big and xs are essentially the same. :

> with partition (p x) xs | partition-size (p x) xs

> ... | small , big | small-size , big-size = small' ++ [ x ] ++ big'

> where

> small' = quicksort' small (g small small-size)

> big' = quicksort' big (g big big-size)

> quicksort : List A → List A

> quicksort xs = quicksort' xs (wf xs)

June 14, 2010This part two of a six part introduction to c2hs. Today, we discuss getting the damn thing to compile in the first place.

Reader prerequisites. You should know how to write, configure and build a vanilla Cabal file for pure Haskell. Fortunately, with cabal init, this is easier than ever. I’ll talk about how to setup a Cabal file for linking in C files, which is applicable to any sort of FFI writing (as it turns out, enabling c2hs is the trivial bit).

Enabling c2hs. Trick question; Cabal will automatically detect files with the extension chs and run c2hs with appropriate flags on them. However, since this operation might fail if the user hasn’t installed c2hs, you should add the following line to your Cabal file:

Build-tools: c2hs

You should be able to compile an empty Haskell module that has chs as its file extension now.

(There is some Cabal hook code for adding c2hs preprocessor support, but it is completely unnecessary.)

Looking at the resulting hs. Once a chs file has been preprocessed, Cabal will not look at it any more. You should not be afraid of looking at the preprocessor output; in many cases, it will be far more elucidating when you’re trying to fix a type error. In general, the hs file will be located in the dist/build directory, as this build message (generated by GHC, not c2hs) shows:

Building abcBridge-0.1...

[ 5 of 11] Compiling Data.ABC.Internal.VecPtr (

dist/build/Data/ABC/Internal/VecPtr.hs,

dist/build/Data/ABC/Internal/VecPtr.o )

The code you see will look something like this:

-- GENERATED by C->Haskell Compiler, version 0.16.2 Crystal Seed, 24 Jan 2009 (Haskell)

-- Edit the ORIGNAL .chs file instead!

{-# LINE 1 "src/Data/ABC/Internal/VecPtr.chs" #-}{-# LANGUAGE ForeignFunctionInterface #-}

module Data.ABC.Internal.VecPtr where

The LINE pragmas ensure that when a type error is generated by the resulting Haskell code, you will get back line numbers that refer to the original chs file. This is not error-proof; sometimes errors will show up one or two lines where c2hs claims the error is.

Imports and language features. c2hs generates Haskell code that needs some language features and imports. You should explicitly add the ForeignFunctionInterface language pragma to the top of your program; while it is possible to enable this via the Cabal file, it’s good form to make your hs files as standalone as possible.

In the current version of c2hs, module imports are a little more subtle. c2hs has a legacy module named C2HS that performs imports, re-exports and extra marshalling functions (necessary only if you’re using fun) that C2HS may generate by default. However, it is on its way to the dustbin, and the c2hs Cabal package doesn’t actually supply this module: you need to copy it into your source directory with c2hs -l. This module depends on haskell98. You should not re-export this module, so it should go in your Other-modules Cabal field.

The modern approach is to do the imports and definitions explicitly yourself. The modules to import are Foreign and Foreign.C, and there is a small assortment of marshalling functions that Haskell will complain are not defined when you try to use fun with that marshaller. Future versions of c2hs will further reduce the necessary functions. gtk2hs takes this approach (although they also forgo most of C2HS’s automated marshalling support).

Loading the library. If you are lucky, your package manager has the library you’d like to create bindings for available. In this case, you only need to add the name of the library to Extra-libraries in the Library section of your Cabal. For example, if you want to use readline, add readline to your field, and GHC will know to find the headers in /usr/include/readline and dynamically link in /usr/lib/libreadline.so. In some cases, a library will install itself in a standard location that is not searched for by default (for example, Oracle on Linux systems, and basically any library on Windows); in this case, you can tell Cabal where this “non-standard standard” location is with Extra-lib-dirs.

If your C library is not a good citizen (which is the case with many niche libraries), some extra steps need to be taken. Here are some common situations, and suggestions for how to deal with them:

- The library is small and has a simple build process. In this case, it is feasible to bundle the library’s source with your package and manage its compilation entirely with Cabal. If your library offers no

make install, this may be your only option, besides asking your users to manually supply the necessary linker options to hook up the two installs (not a very user-friendly option, in particular, it makes running cabal install complicated). You should only do this with small amounts of source code, since the GHC-directed compilation is much slower than a usual build. See Compiling the library with Cabal and Managing includes. - I want to bundle the library for X reason, but its build process is complicated. In such a case, it is possible to setup Cabal to call the libraries build process, and then use the resulting files for the Haskell build process. There are numerous disadvantages to this, including a messy Cabal file and a messy install process, so if you’re able to do (3), I recommend that instead. See Compiling the library with hooks for details. You should also read Managing includes.

- I don’t want to bundle the library. In this case, you will need to give instructions for end-users to download, compile and install the external library. It will be a lot easier for users if you, the package author, go and package the library for various distributions, so that it becomes a well-behaved, albeit seldom installed, library. If a user is unwilling to install the library in the canonical paths, they will need to pass

cabal the appropriate options. See Manual linking.

Compiling the library with Cabal. Cabal has the ability to compile C code in a very simple fashion: it takes a list of files from the Cabal field C-sources and compiles them in that order. In particular, it doesn’t do any dependency tracking, so when you feed it the list of files, make sure they’re in the right order! This makes this mechanism appropriate only for small amounts of C, including C that you may write yourself to aid the binding process. There is a growing convention to place c files in cbits, and h files in include. You can then tell Cabal about these directories with the following lines:

-- This ensures that Cabal places these files in the release tarball,

-- which is important if you plan to release

Extra-source-files: cbits, include

-- ...

Library foobar

-- ...

-- The C source files to compile, in that order

C-sources: cbits/foobar.c, cbits/foobaz.c

-- The location of the header files

Include-dirs: include

-- The header files to be included

Includes: foobar.h, foobaz.h

-- Header files to install

Install-includes: foobar.h, foobaz.h

A few words about the “includes” fields:

- The

Includes field will probably not make a user-visible difference when the compilation goes well. However, it is good form to specify because Cabal will then go and check that those include files exist and are usable prior to compilation, giving the user a better error message if there are problems. Usage. Specify any standard headers and any bundled headers that your package uses. - The

Install-includes field will cause Cabal to place those header files in a public location upon installation. This is necessary for older versions of GHC to compile your code or if modules that use your module need to perform C includes of your library or cbits; it’s generally good form to install your headers. Usage. Specify just the bundled headers that your package uses and exports.

Compiling the library with hooks. If there are over a dozen C files to be compiled, you may want to let the traditional configure && make process handle things for you. In this case, it may be appropriate to setup a small hook in Cabal’s Setup.hs using the experimental hooks interface to invoke the compilation. Here is a simple sample build script:

import Distribution.Simple

import Distribution.Simple.Setup

import Distribution.Simple.Utils (rawSystemExit)

main = defaultMainWithHooks simpleUserHooks

{ preBuild = \a b -> makeLib a b >> preBuild simpleUserHooks a b }

makeLib :: Args -> BuildFlags -> IO ()

makeLib _ flags =

rawSystemExit (fromFlag $ buildVerbosity flags) "env"

["CFLAGS=-D_LIB", "make", "--directory=abc", "libabc.a"]

We’ve added our own makeLib build script to the preBuild (while preserving the old simpleUserHooks version), and use a Cabal utility function rawSystemExit to do most of the lifting for us. Notice that --directory=abc needed to be passed to make; Cabal runs in the same directory as the cabal file, and so you’ll probably need to adjust your working directory to the library directory. setCurrentDirectory may come in handy.

Your build process will probably place the resulting libfoo.a file somewhere not dist/build. You can tell Cabal to look in that directory using the Extra-lib-dirs field.

The above steps are enough to get a clean source checkout of your software working, but to ensure that users will be able to install the result of cabal sdist, you will need to go a little further.

First, any source file that the build processes you will need to explicitly list in Extra-source-files. Cabal only affords a limited form of globbing, which must be in the filename and contain a file extension, so this list can get quite long (and we recommend you generate it with a script.)

Second, the static/dynamic libraries that the build process creates probably will not be placed in a place that GHC will look when compiling, resulting in this error:

Linking dist/build/abc-test/abc-test ...

/usr/bin/ld: cannot find -labc

collect2: ld returned 1 exit status

We can place our library in the same place where Cabal places the static libraries of Haskell modules during installation with another hook:

import Distribution.Simple

import Distribution.Simple.Setup

import Distribution.Simple.Utils (rawSystemExit)

import Distribution.PackageDescription (PackageDescription(..))

import Distribution.Simple.LocalBuildInfo (

LocalBuildInfo(..), InstallDirs(..), absoluteInstallDirs)

main = defaultMainWithHooks simpleUserHooks

{ preConf = \a f -> makeAbcLib a f >> preConf simpleUserHooks a f

, copyHook = copyAbcLib

}

-- ...

copyAbcLib :: PackageDescription -> LocalBuildInfo -> UserHooks -> CopyFlags -> IO ()

copyAbcLib pkg_descr lbi _ flags = do

let libPref = libdir . absoluteInstallDirs pkg_descr lbi

. fromFlag . copyDest

$ flags

rawSystemExit (fromFlag $ copyVerbosity flags) "cp"

["abc/libabc.a", libPref]

The incant to the right of libPref determines where Cabal is going to install the library files, and then we simply copy our libraries to that location.

(Nota bene. You should really only use this trick if you’re sure no one is going to install this library globally, because having non-binary compatible libraries floating around with the same name is no fun at all.)

Managing includes. Any non-standard directories that need to be in the include path should be added to Include-dirs. If there are a lot of such directories in the library, consider an alternate solution: create symlinks to all of the relevant header files in include and then just add that directory to Include-dirs.

Manual linking. If you need to manually tell Cabal where the relevant headers and libraries are, you can use the --extra-include-dirs and --extra-lib-dirs flags with cabal configure or cabal install. They function just like Include-dirs and Extra-lib-dirs.

Cohabiting Library and Executable sections. You may find it convenient to define a number of Executable sections in your Cabal file for testing, in which case you’ll notice that you seem to need to duplicate all of the C-related Cabal fields to each of your executable sections. Well, in Cabal 1.8.0.4, you can now set Build-depends to point to your same package (“self-reference”); so you declare a Build-depends on your own package for each executable and the C-related Cabal fields are unnecessary.

You will need to tell Cabal that it’s OK to use this feature with this field:

Cabal-version: >= 1.8.0.4

Postscript. Thanks Duncan Coutts for helping clarify and suggest improvements sections of this tutorial.

Next time. Principles of FFI API design.

June 11, 2010This post is part of what I hope will be a multi-part tutorial/cookbook series on using c2hs (Hackage).

- The Haskell Preprocessor Hierarchy (this post)

- Setting up Cabal, the FFI and c2hs

- Principles of FFI API design

- First steps in c2hs

- Marshalling with get an set

- Call and fun: marshalling redux

What’s c2hs? c2hs is a Haskell preprocessor to help people generate foreign-function interface bindings, along with hsc2hs and GreenCard. The below diagram illustrates how the preprocessors currently supported by Cabal fit together. (For the curious, Cpp is thrown in with the rest of the FFI preprocessors, not because it is particularly useful for generating FFI code, but because many of the FFI preprocessors also implement some set of Cpp’s functionality. I decided on an order for Alex and Happy on the grounds that Alex was a lexer generator, while Happy was a parser generator.)

What does c2hs do? Before I tell you what c2hs does, let me tell you what it does not do: it does not magically eliminate your need to understand the FFI specification. In fact, it will probably let you to write bigger and more ambitious bindings, which in turn will test your knowledge of the FFI. (More on this later.)

What c2hs does help to do is eliminate some of the drudgery involved with writing FFI bindings. (At this point, the veterans who’ve written FFI bindings by hand are nodding knowingly.) Here are some of the things that you will not have to do anymore:

- Port enum definitions into pure Haskell code (this would have meant writing out the data definition as well as the Enum instance),

- Manually compute the sizes of structures you are marshalling to and from,

- Manually compute the offsets to peek and poke at fields in structures (and deal with the corresponding portability headaches),

- Manually write types for C pointers,

- (To some extent) writing the actual

foreign import declarations for C functions you want to use

When should I use c2hs? There are many Haskell pre-processors; which one should you use? A short (and somewhat inaccurate) way to characterize the above hierarchy is the further down you go, the less boilerplate you have to write and the more documentation you have to read; I have thus heard advice that hsc2hs is what you should use for small FFI projects, while c2hs is more appropriate for the larger ones.

Things that c2hs supports that hsc2hs does not:

- Automatic generation of

foreign import based on the contents of the C header file, - Semi-automatic marshalling to and from function calls, and

- Translation of pointer types and hierarchies into Haskell types.

Things that GreenCard supports and c2hs does not:

- Automatic generation of

foreign import based on the Haskell type signature (indeed, this is a major philosophical difference), - A more comprehensive marshalling language,

- Automatic generation of data marshalling using Data Interface schemes.

Additionally, hsc2hs and c2hs are considered quite mature; the former is packaged with GHC, and (a subset of) the latter is used in gtk2hs, arguably the largest FFI binding in Haskell. GreenCard is a little more, well, green, but it recently received a refresh and is looking quite promising.

Is this tutorial series for me? Fortunately, I’m not going to assume too much knowledge about the FFI (I certainly didn’t have as comprehensive knowledge about it going in than I do coming out); however, some understanding of C will be assumed in the coming tutorials. In particular, you should understand the standard idioms for passing data to and out of C functions and feel comfortable tangling with pointers (though there might be a brief review there too).

Next time. Setting up Cabal, the FFI and c2hs.

June 9, 2010Bjarne Stroustrup once boasted, “C++ is a multi-paradigm programming language that supports Object-Oriented and other useful styles of programming. If what you are looking for is something that forces you to do things in exactly one way, C++ isn’t it.” But as Taras Glek wryly notes, most of the static analysis and coding standards for C++ are mostly to make sure developers don’t use the other paradigms.

On Tuesday, Taras Glek presented Large-Scale Static Analysis at Mozilla. You can watch the video at Galois’s video stream. The guiding topic of the talk is pretty straightforward: how does Mozilla use static analysis to manage the millions of lines of code in C++ and JavaScript that it has? But there was another underlying topic: static analysis is not just for the formal-methods people and the PhDs; anyone can and should tap into the power afforded by static analysis.

Since Mozilla is a C++ shop, the talk was focused on tools built on top of the C++ language. However, there were four parts to static analysis that Taras discussed, which are broadly applicable to any language you might perform static analysis in:

- Parsing. How do you convert a text file into an abstract representation of the source code (AST)?

- Semantic grep. How do you ask the AST for information?

- Analysis. How do you restrict valid ASTs?

- Refactoring. How do you change the AST and write it back?

Parsing. Parsing C++ is hard. Historically this is the case because it inherited a lot of syntax from C; technically this is the case because it is an extremely ambiguous grammar that requires semantic knowledge to disambiguate. Taras used Elsa (which can parse all of Mozilla, after Taras fixed a bunch of bugs), and awaits eagerly awaits Clang to stabilize (as it doesn’t parse all of Mozilla yet.) And of course, the addition of the plugin interface to GCC 4.5 means that you can take advantage of GCC’s parsing capabilities, and many of the later stage tools are built upon that.

Semantic grep. grep is so 70’s! If you’re lucky, the maintainers of your codebase took care to follow the idiosyncratic rules that make code “more greppable”, but otherwise you’ll grep for an identifier and get pages of results and miss the needle. If you have an in-memory representation of your source, you can intelligently ask for information. Taken further, this means better code browsing like DXR.

Consider the following source code view. It’s what you’d expect from a source code browser: source on the right, declarations on the left.

Let’s pick an identifier from the left, let’s say CopyTo. Let’s first scroll through the source code and see if we can pick it out.

Huh! That was a really short class, and it was no where to be found. Well, let’s try clicking it.

Aha! It was in the macro definition. The tool can be smarter than the untrained eye.

Analysis. For me, this was really the flesh of the talk. Mozilla has a very pimped out build process; hooking into GCC with Dehydra and Treehydra. The idea behind the Dehydra project is to take the internal structures that GCC provides to plugins, and convert them into a JSON-like structure (JSON-like because JSON is acyclic but these structures are cyclic) that Dehydra scripts, which are written in JavaScript can be run on the result. These scripts can emit errors and warnings, which look just like GCC build errors and warnings. Treehydra is an advanced version of Dehydra, that affords more flexibility to the analysis script writer.

So, what makes Dehydra/Treehydra interesting?

- JavaScript. GCC’s plugin interface natively supports C code, which may be intimidating to developers with no static analysis experience. Porting these structures to JavaScript means that you get a high-level language to play in, and also lets you tell Junior developers without a lick of static analysis experience, “It’s just like hacking on a web application.” It means that you can just print out the JSON-like structure, and eyeball the resulting structure for the data you’re looking for; it means when your code crashes you get nice backtraces. Just like Firefox’s plugin interface, Dehydra brings GCC extensions to the masses.

- Language duct tape. I took a jab at Stroustrup at the beginning of his post, and this is why. We can bolt on extra language features like

final for classes (with attributes, __attribute__((user("NS_final"))) wrapped up in a macro NS_FINAL_CLASS) and other restrictions that plain C++ doesn’t give you. - Power when you need it. Dehydra is a simplified interface suitable for people without static analysis or compiler background; Treehydra is full-strength, intended for people with such backgrounds and can let you do things like control-flow analysis.

All of this is transparently integrated into the build system, so developers don’t have to fumble with an external tool to get these analyses.

Refactoring. Perhaps the most ambitious of them all, Taras discussed refactoring beyond the dinky Extract method that Java IDEs like Eclipse give you using Pork. The kind of refactoring like “rewrite all of Mozilla to use garbage collection instead of reference counting.” When you have an active codebase like Mozilla’s, you don’t have the luxury to do a “stop all development and start refactoring…for six years” style refactoring. Branches pose similar problems; once the major refactoring lands on one branch, it’s difficult to keep the branch up-to-date with the other, and inevitably one branch kills off the other.

The trick is an automated refactoring tool, because it lets you treat the refactoring as “just another patch”, and continually rebuild the branch from trunk, applying your custom patches and running the refactoring tool to generate a multimegabyte patch to apply in the stack.

Refactoring C++ is hard, because developers don’t just write C++; they write a combination of C++ and CPP (C pre-processor). Refactoring tools need to be able to reconstruct the CPP macros when writing back out, as opposed to languages like ML which can get away with just pretty-printing their AST. Techniques include pretty-printing as little as possible, and forcing the parser to give you a log of all of the pre-processor changes it made.

Open source. Taras left us with some words about open-source collaboration, that at least the SIPB crowd should be well aware of. Don’t treat tools you depend on black boxes: they’re open-source! If you find a bug in GCC, don’t just work around it, check out the source, write a patch, and submit it upstream. It’s the best way to fix bugs, and you score instant credibility for bugs you might submit later. There is a hierarchy of web applications to browsers, browsers to compilers, compilers to operating systems. The advantage of an open-source ecosystem is that you can read the source all the way down. Use the source, Luke.

June 7, 2010Attention conservation notice. The author reminisces about learning physics in high school, and claims that all too often, teaching was focused too much on concrete formulas, and not the unifying theory around them.

In elementary school, you may have learned D=RT (pronounced “dirt”), that is, distance is rate multiplied with time. This was mostly lies, but it was okay, because however tenuous the equation’s connection to the real world, teachers could use it to introduce the concept of algebraic manipulation, the idea that with just D=RT, you could also find out R if you knew D and T, and T if you knew D and R. Unless you were unusually bright, you didn’t know you were being lied to; you just learned to solve the word problems they’d give you.

Fast forward to high school physics. The lie is still preached, though dressed in slightly different clothes: “Position equals velocity times time,” they say. But then the crucial qualifier would be said: “This equation is for uniform motion.” And then you’d be introduced to your friend uniform acceleration, and there’d be another equation to use, and by the time you’d finish the month-long unit on motion, you’d have a veritable smörgåsbord of equations and variables to keep track of.

CollegeBoard AP Physics continues this fine tradition, as stated by their equation sheet:

$v = v_0 + at$

$x = x_0 + v_0t + \frac12at^2$

With the implicit expectation that the student knows what each of these equations means, and also the inadvertent effect of training students to pattern match when an equation is appropriate and which values go to which variables.

I much prefer this formulation:

$v = \int a\ dt$

$x = \int v\ dt$

With these two equations, I tap into calculus, and reach the very heart of the relationship between position, velocity and acceleration: one is merely the derivative of the previous. These equations are fully general (not only do they work for non-uniform motion, they work on arbitrary-dimensional vectors too), compact and elegant. They’re also not immediately useful from a calculational standpoint.

Is one more valuable than the other? They are good for different things: the first set is more likely to help you out if you want to calculate how long it will take for an apple to fall down from a building, neglecting air resistance. But the second set is more likely to help you really understand motion as more than just a set of algebraic manipulations.

I was not taught this until I took the advanced Classical Mechanics class at MIT. For some reason it is considered fashionable to stay stuck in concrete formulas than to teach the underlying theory. AP Physics is even worse: even AP Physics C, which purports to be more analytical, fills its formula sheet with the former set of equations.

Students have spent most of grade school learning how to perform algebraic manipulations. After taking their physics course, they will likely go on to occupations that involve no physics at all, all of that drilling on exercises wasted. They deserve better than to be fed more algebraic manipulations; they deserve to know the elegance and simplicity that is Classical Mechanics.

Postscript. For programmers reading this blog, feel free to draw your own analogies to your craft; I believe that other fields of science have much to say on the subject of abstraction. For prospective MIT students reading this blog, you may have heard rumors that 8.012 and 8.022 are hard. This is true; but what it is also true is that this pair of classes have seduced many undergraduates into the physics department. I cannot recommend the pair of classes more highly.

June 4, 2010Update. The video of the talk can be found here: Galois Tech Talks on Vimeo: Categories are Databases.

On Thursday Dr. David Spivak presented Categories are Databases as a Galois tech talk. His slides are here, and are dramatically more accessible than the paper Simplicial databases. Here is a short attempt to introduce this idea to people who only have a passing knowledge of category theory.

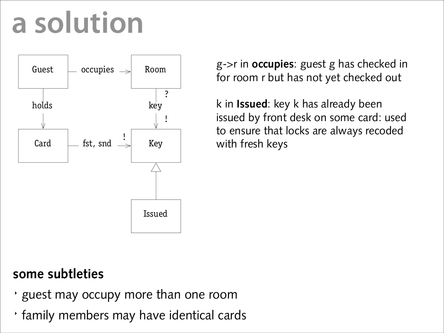

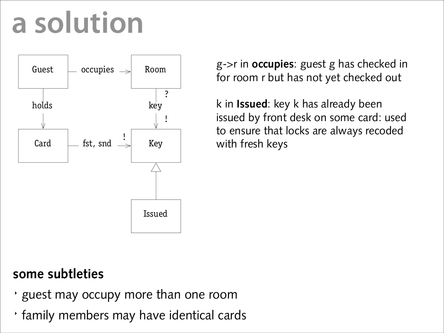

An essential exercise when designing relational databases is the practice of object modeling using labeled graphs of objects and relationships. Visually, this involves drawing a bunch of boxes representing the objects being modeled, and then drawing arrows between the objects showing relationships they may have. We can then use this object model as the basis for a relational database schema.

An example model from a software engineering class is below:

With the image of a object model in your head, consider Wikipedia’s definition of a category:

In mathematics, a category is an algebraic structure consisting of a collection of “objects”, linked together by a collection of “arrows” that have two basic properties: the ability to compose the arrows associatively and the existence of an identity arrow for each object.

The rest of the definition may seem terribly abstract, but hopefully the bolded section seems to clearly correspond to the picture of boxes (objects) and arrows we drew earlier. Perhaps…

Database schema = Category.

Unfortunately, a directed graph is not quite a category; the secret sauce that makes a category a category are those two properties on the arrows, associative composition and identity, and if we really want to strengthen our claim that a schema is a category, we’ll need to demonstrate these.

Recall that our arrows are “relations,” that is, “X occupies Y” or “X is the key for Y”. Our category must have an identity arrow, that is, some relation “X to X”. How about, “X is itself X”, an almost vacuous statement, but one most certainly true. Identity arrow, check.

We also need to show associative composition of arrows. Composition of two arrows is much like they showed you when they were teaching you vector algebra: you take the head of one arrow (X to Y) and smush it with the tail of another (Y to Z), and you get another arrow (X to Z). If a “book has an author” and “an author has a favorite color”, I can say “the book’s author has a favorite color”. This composed statement doesn’t care who the author was… just what his favorite color is. In fact,

Arrow composition = Joins

That is, one of the fundamental features of a category, a feature that any nice result from pure category theory uses as if it were intuitively obvious, is one of the very techniques that does not seem obvious to someone reading about JOINs in the second half of a database tutorial.

(Aside. A foreign key relationship is intrinsically many to one: a foreign key field can only point to one record in another table, but many rows can have that field pointing to the same record. When doing relational modeling, we will frequently use many-to-many or one-to-many relationships. Any database administrator knows, however, that we can simply rewrite these into many to one relationships (reversing the arrow in the case of one-to-many and introducing a new table for many-to-many).)

When we have a schema, we also want to have data to fill the schema. As it turns out, this also fits into a category-theoretic framework too, although a full explanation is out of scope for this post (I suggest consulting the slides.)

Why do you care? There are some good reasons mentioned by Spivak:

I’ll mention one of my own: SQL, while messy, is precise; it can be fed into a computer and turned into a databases that can do real work. On the other hand, relational models are high level but kind of mushy; developers may complain that drawing diagrams with arrows doesn’t seem terribly rigorous and that the formalism doesn’t really help them much.

Category theory is precise; it unambiguously assigns meaning and structure to the relations, the laws of composition define what relations are and aren’t permissible. Category theory is not only about arrows (if it was it’d be pretty boring); rather, it has a rich body of results from many fields expressed in a common language that can “translated” into database-speak. In many cases, important category theory notions are tricky techniques in database administrator folklore. When you talk about arrows, you’re talking a lot more than arrows. That’s powerful!

June 2, 2010Git is very careful about your files: unless you tell it to be explicitly destructive, it will refuse to write over files that it doesn’t know about, instead giving an error like:

Untracked working tree file ‘foobar’ would be overwritten by merge.

In my work with Wizard, I frequently need to perform merges on working copies that have been, well, “less than well maintained”, e.g. they untarred a new version of the the source tree on the old directory and forgot to add the newly added files. When Wizard goes in and tries to automatically upgrade them to the new version the proper way, this results in all sorts of untracked working tree file complaints, and then we have to go and manually check on the untracked files and remove them once they’re fine.

There is a simple workaround for this: while we don’t want to add all untracked files to the Git repository, we could add just the files that would be clobbered. Git will then stop complaining about the files, and we will still have records of them in the history:

def get_file_set(rev):

return set(shell.eval("git", "ls-tree", "-r", "--name-only", rev).split("\n"))

old_files = get_file_set("HEAD")

new_files = get_file_set(self.version)

added_files = new_files - old_files

for f in added_files:

if os.path.lexists(f): # *

shell.call("git", "add", f)

Previously, the starred line of code read if os.path.exists(f). Can you guess why this was buggy? Recall the difference betweeen exists and lexists; if the file in question is a symlink, exists will follow it, while lexists will not. So, if a file to be clobbered is a broken symlink, the old version of the code would not have removed it. In many case, you can’t distinguish between the cases: if the parent directory of the file that the symlink points to exists, I can create a file via the symlink, and other normal “file operations.”

However, Git is very keenly aware of the difference between a symlink and a file and will complain accordingly if it would have clobbered a symlink. Good ole information preservation!

Postscript. Yesterday was my first day of work at Galois! It was so exciting that I couldn’t get my wits together to write a blog post about it. More to come.

May 31, 2010Conservation attention notice. What definitions from the Haskell 98 Prelude tend to get hidden? I informally take a go over the Prelude and mention some candidates.

(.) in the Prelude is function composition, that is, (b -> c) -> (a -> b) -> a -> c. But the denizens of #haskell know it can be much more than that: the function a -> b is really just the functor, so a more general type is Functor f => (b -> c) -> f b -> f c, i.e. fmap. Even more generally, (.) can indicate morphism composition, as it does in Control.Category.

all, and, any, concat, concatMap, elem, foldl, foldl1, foldr, foldr1, mapM_, maximum, minimum, or, product, sequence_. These are all functions that operate on lists, that easily generalize to the Foldable type class; just replace [a] with Foldable t => t a. They can be found in Data.Foldable.

mapM, sequence. These functions generalize to the Traversable type class. They can be found in Data.Traversable.

Any numeric function or type class. Thurston, Thielemann and Johansson wrote numeric-prelude, which dramatically reorganized the hierarchy of numeric classes and generally moved things much closer to their mathematical roots. While dubbed experimental, it’s seen airplay in more mathematics oriented Haskell modules such as Yorgey’s species package.

Any list function. Many data structures look and smell like lists, and support some set of the operations analogous to those on lists. Most modules rely on naming convention, and as a result, list-like constructs like vectors, streams, bytestrings and others ask you to import themselves qualified. However, there is Data.ListLike which attempts to encode similarities between these. Prelude.Listless offers a version of the Prelude minus list functions.

Monad, Functor. It is widely believed that Monad should probably be an instance of Applicative (and the category theorists might also have you insert Pointed functors in the hierarchy too.) The Other Prelude contains this other organization, although it is cumbersome to use in practice since the new class means most existing monad libraries are not usable.

repeat, until. There is an admittedly oddball generalization for these two functions in Control.Monad.HT. In particular, repeat generalizes the identity monad (explicit (un)wrapping necessary), and until generalizes the (->) a monad.

map. It’s fmap for lists.

zip, zipWith, zipWith3, unzip. Conal’s Data.Zip generalize zipping into the Zip type class.

IO. By far you’ll see the most variation here, with a multitude of modules working on many different levels to give extra functionality. (Unfortunately, they’re not really composable…)

- System.IO.Encoding makes the IO functions encoding aware, and uses implicit parameters to allow for a “default encoding.” Relatedly, System.UTF8IO exports functions just for UTF-8.

- System.IO.Jail lets you force input-output to only take place on whitelisted directories and/or handles.

- System.IO.Strict gives strict versions of IO functions, so you don’t have to worry about running out of file handles.

- System.Path.IO, while not quite IO per se, provides typesafe filename manipulation and IO functions to use those types accordingly.

- System.IO.SaferFileHandles allows handles to be used with monadic regions, and parametrizes handles on the IO mode they were opened with. System.IO.ExplicitIOModes just handles IOMode.