August 5, 2010Bonus post today! Last Tuesday, John Erickson gave a Galois tech talk entitled “Industrial Strength Distributed Explicit Model Checking” (video), in which he describe PReach, an open-source model checker based on Murphi that Intel uses to look for bugs in its models. It is intended as a simpler alternative to Murphi’s built-in distributed capabilities, leveraging Erlang to achieve much simpler network communication code.

First question. Why do you care?

- Model checking is cool. Imagine you have a complicated set of interacting parallel processes that evolve nondeterministically over time, using some protocol to communicate with each other. You think the code is correct, but just to be sure, you add some assertions that check for invariants: perhaps some configurations of states should never be seen, perhaps you want to ensure that your protocol never deadlocks. One way to test this is to run it in the field for a while and report when the invariants fail. Model checking lets you comprehensively test all of the possible state evolutions of the system for deadlocks or violated invariants. With this, you can find subtle bugs and you can find out precisely the inputs that lead to that event.

- Distributed applications are cool. As you might imagine, the number of states that need to be checked explodes exponentially. Model checkers apply algorithms to coalesce common states and reduce the state space, but at some point, if you want to test larger models you will need more machines. PReach has allowed Intel to run the underlying model checker Murphi fifty times faster (with a hundred machines).

This talk was oriented more towards to the challenges that the PReach team encountered when making the core Murphi algorithm distributed than how to model check your application (although I’m sure some Galwegians would have been interested in that aspect too.) I think it gave an excellent high level overview of how you might design a distributed system in Erlang. Since the software is open source, I’ll link to relevant source code lines as we step through the high level implementation of this system.

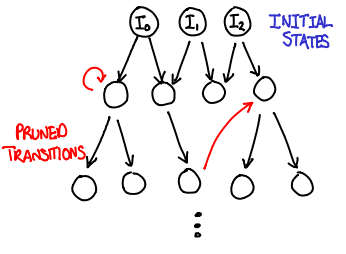

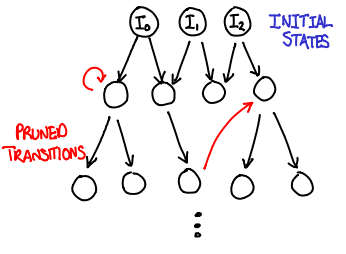

The algorithm. At its heart, model checking is simply a breadth-first search. You take the initial states, compute their successor states, and add those states to the queue of states to be processed. :

WQ : list of state // work queue

V : set of state // visited states

WQ := initial_states()

while !empty(WQ) {

s = dequeue(WQ)

foreach s' in successors(s) {

if !member(s', V) {

check_invariants(s')

enqueue(s', WQ)

add_element(s', V)

}

}

}

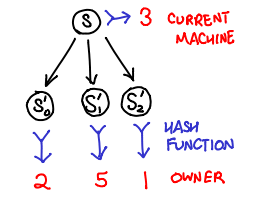

The parallel algorithm. We now need to make this search algorithm parallel. We can duplicate the work queues across computers, making the parallelization a matter of distributing the work load across a number of computers. However, the set of visited states is trickier: if we don’t have a way of partitioning it across machines, it becomes shared state and a bottleneck for the entire process.

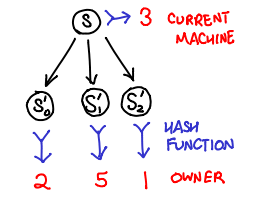

Stern and Dill (PS) came up with a clever workaround: use a hash function to distribute states to processors. This has several important implications:

- If the hash function is uniform, we now can distribute work evenly across the machines by splitting up the output space of the function.

- Because the hash function is deterministic, any state will always be sent to the same machine.

- Because states are sticky to machines, each machine can maintain an independent visited states and trust that if a state shows up twice, it will get sent to the same machine and thus show up in the visited states of that machine.

One downside is that a machine cannot save network latency by deciding to process it’s own successor states locally, but this is a fair tradeoff for not having to worry about sharing the visited states, which is considered a hard problem to do efficiently.

The relevant source functions that implement the bulk of this logic are recvStates and reach.

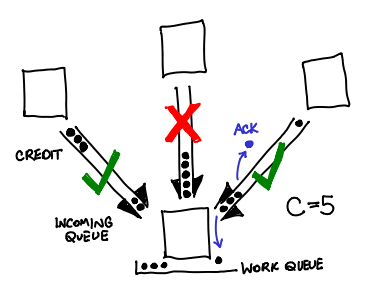

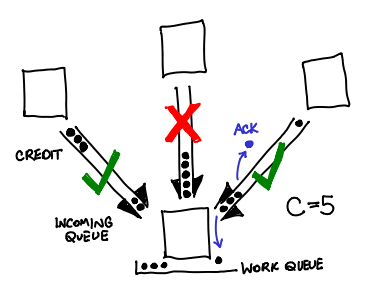

Crediting. When running early versions of PReach, the PReach developers would notice that occasionally a machine in the cluster would massively slow down or crash nondeterministically.

It was discovered that this machine was getting swamped by incoming states languishing in the in-memory Erlang request queue: even though the hash function was distributing the messages fairly evenly, if a machine was slightly slower than its friends, it would receive states faster than it could clear out.

To fix this, PReach first implemented a back-off protocol, and then implemented a crediting protocol. The intuition? Don’t send messages to a machine if it hasn’t acknowledged your previous C messages. Every time a message is sent to another machine, a credit is sent along with it; when the machine replies back that it has processed the state, the credit is sent back. If there are no credits, you don’t send any messages. This bounds the number of messages in the queue to be N * C, where N is the number of nodes (usually about a 100 when Intel runs this). To prevent a build-up of pending states in memory when we have no more credits, we save them to disk.

Erickson was uncertain if Erlang had a built-in that performed this functionality; to him it seemed like a fairly fundamental extension for network protocols.

Load balancing. While the distribution of states is uniform, once again, due to a heterogeneous environment, some machines may be able to process states faster than other. If those machines finish all of their states, they may sit idly by, twiddling their thumbs, while the slower machines still work on their queue.

One thing to do when this happens is for the busy nodes to notice that a machine is idling, and send them their states. Erickson referenced some work by Kumar and Mercer (PDF) on the subject. The insight was that overzealous load balancing was just as bad as no load balancing at all: if the balancer attempts to keep all queues exactly the same, it will waste a lot of network time pushing states across the network as the speeds of the machines fluctuate. Instead, only send states when you notice someone with X times less states than you (where X is around 5.)

One question that might come up is this: does moving the states around in this fashion cause our earlier cleverness with visited state checking to stop working? The answer is fortunately no! States on a machine can be in one of two places: the in-memory Erlang receive queue, or the on-disk work queue. When transferring a message from the receive to the work queue, the visited test is performed. When we push states to a slacker, those states are taken from our work queue: the idler just does the invariant checking and state expansion (and also harmlessly happens to add that state to their visited states list).

Recovering shared states. When an invariant fails, how do you create a backtrace that demonstrates the sequence of events that lead to this state? The processing of any given state is scattered across many machines, which need to get stitched together again. The trick is to transfer not only the current state when passing off successors, but also the previous state. The recipient then logs both states to disk. When you want to trace back, you can always look at the previous state and hash it to determine which machine that state came from.

In the field. Intel has used PReach on clusters of up to 256 nodes to test real models of microarchitecture protocols of up to thirty billion states (to Erickson’s knowledge, this is the largest amount of states that any model checker has done on real models.)

Erlang pain. Erickson’s primary complaint with Erlang was that it did not have good profiling facilities for code that interfaced heavily with C++; they would have liked to have performance optimized their code more but found it difficult to pin down where the slowest portions were. Perhaps some Erlang enthusiasts have some comments here?

August 4, 2010While attempting to figure out how I might explain lazy versus strict bytestrings in more depth without boring half of my readership to death, I stumbled upon a nice parallel between a standard implementation of buffered streams in imperative languages and iteratees in functional languages.

No self-respecting input/output mechanism would find itself without buffering. Buffering improves efficiency by grouping reads or writes together so that they can be performed as a single unit. A simple read buffer might be implemented like this in C (though, of course, with the static variables wrapped up into a data structure… and proper handling for error conditions in read…):

static char buffer[512];

static int pos = 0;

static int end = 0;

static int fd = 0;

int readChar() {

if (pos >= end && feedBuf() == 0) {

return EOF;

}

return (int) buffer[pos++];

}

int feedBuf() {

pos = 0;

end = read(fd, buffer, sizeof(buffer));

assert(end != -1);

return end;

}

The exported interface is readChar, which doles out a single char cast to an int every time a user calls it, but behind the scenes only actually reads from the input if it has run out of buffer to supply (pos >= end).

For most applications, this is good enough: the chunky underlying behavior is hidden away by a nice and simple function. Furthermore, our function is not too simple: if we were to read all of standard input into one giant buffer, we wouldn’t be able to do anything else until the EOF comes along. Here, we can react as the input comes in.

What would such a set of functions look like in a purely functional setting? One obvious difficulty is the fact that buffer is repeatedly mutated as we perform reads. In the spirit of persistence, we should very much prefer that our buffer not be mutated beyond when we initially fill it up. Making the buffer persistent means we also save ourselves from having to copy the data out if we want to hold onto it while reading in more data (you could call this zero copy). We can link buffers together using something simple: say, a linked list.

Linked lists eh? Let’s pull up the definition for lazy and strict ByteStrings (slightly edited for you, the reader):

data Strict.ByteString = PS !(ForeignPtr Word8) !Int !Int

data Lazy.ByteString = Empty | Chunk !Strict.ByteString Lazy.ByteString

In C, these would be:

struct strict_bytestring {

char *pChar;

int offset;

int length;

}

struct lazy_bytestring {

struct strict_bytestring *cur;

int forced;

union {

struct lazy_bytestring *next;

void (*thunk)(struct lazy_bytestring*);

}

}

The Strict.ByteString is little more than a glorified, memory-managed buffer: the two integers track offset and length. Offset is an especially good choice in the presence of persistence: taking a substring of a string no longer requires a copy: just create a new strict ByteString with the offset and length set appropriately, and use the same base pointer.

So what is Lazy.ByteString? Well, it’s a glorified lazy linked list of strict ByteStrings—just read Chunk as Cons, and Empty as Null: the laziness derives from the lack of strictness on the second argument of Chunk (notice the lack of an exclamation mark, which is a strictness annotation). The laziness is why we have the thunk union and forced boolean in our lazy_bytestring struct: this API scribbles over the function pointer with the new lazy_bytestring when it is invoked. (This is not too different from how GHC does it; minus a layer of indirection or so.) If we ignore the laziness, this sounds a bit like the linked list of buffers we described earlier.

There is an important difference, however. A Lazy.ByteString is pure: we can’t call the original read function (a syscall, which makes it about as IO as you can get). So lazy ByteStrings are appropriate for when we have some pure computation (say, a Markov process) which can generate infinite amounts of text, but are lacking when it comes to buffering input.

“No problem!” you might say, “Just change the datatype to hold an IO Lazy.ByteString instead of a Lazy.ByteString:

data IO.ByteString = Empty | Chunk !Strict.ByteString (IO IO.ByteString)

But there’s something wrong about this datatype: nothing is stopping someone from invoking IO IO.ByteString multiple times. In fact, there’s no point in placing the IO operation in the Chunk value: due to the statefulness of file descriptors, the IO operation is the same code every time: hReadByteString handle. We’re back to handle-based IO.

The idea of IO.ByteString as a list is an important intuition, however. The key insight is this: who said that we have to give the list of IO actions to the user? Instead, invert the control so that the user doesn’t call the iteratee: the iteratee calls the user with the result of the IO. The user, in turn, can initiate other IO, or compose iteratees together (something we have not discussed) to stream from one iteratee to another.

At this point, I defer to Oleg’s excellent annotated slides (PDF) for further explanation of iteratees (no really, the slides are extremely well written), as well as the multitude of iteratee tutorials. My hope is that the emphasis on the “linked list of buffers” generated by IO operations directs some attention towards the fundamental nature of an iteratee: an abstraction on top of a list of IO actions.

To summarize:

- Use strict bytestrings as a primitive for building more interesting structures that have buffers (though avoid reimplementing lazy bytestrings or iteratees). Use them when the amount of data is small, when all of it can be initialized at once, or when random access, slicing and other non-linear access patterns are important.

- Use lazy bytestrings as a mechanism for representing infinite streams of data generated by pure computation. Consider using them when performing primarily operations well suited for lazy lists (

concat, append, reverse etc). Avoid using them for lazy IO (despite what the module says on the tin). - Use iteratees for representing data from an IO source that can be incrementally processed: this usually means large datasets. Iteratees are especially well suited for multiple layers of incremental processing: they “fuse” automatically and safely.

August 2, 2010Notice. Following a critique from Bryan O’Sullivan, I’ve restructured the page.

“How do the different text handling libraries compare, and when should we use which package?” asks Chris Eidhof. The latter question is easier to answer. Use bytestring for binary data—raw bits and bytes with no explicit information as to semantic meaning. Use text for Unicode data representing human written languages, usually represented as binary data equipped with a character encoding. Both (especially bytestring) are widely used and are likely to become—if they are not already—standards.

There are, however, a lot more niche string handling libraries on Hackage. Having not used all of them in substantial projects, I will refrain on judging them on stability or implementation; instead, we’ll categorize them on the niche they fill. There are several axes that a string library or module may be categorized on:

- Binary or text? Binary is raw bits and bytes: it carries no explicit information about what a

0 or 0x0A means. Text is meant to represent human language and is usually binary data equipped with a character encoding. This is the most important distinction for a programmer to know about. - If text, ASCII, 8-bit or Unicode? ASCII is simple but English-only; 8-bit (e.g. Latin-1) is ubiquitous and frequently necessary for backwards compatibility; Unicode is the “Right Way” but somewhat complicated. Unicode further asks, What in-memory encoding? UTF-16 is easy to process while UTF-8 can be twice as memory efficient for English text. Most languages pick Unicode and UTF-16 for the programmer.

- Unpacked or packed? Unpacked strings, the native choice, are just linked lists of characters. Packed strings are classic C arrays, allowing efficient processing and memory use. Most languages use packed strings: Haskell is notable (or perhaps notorious) in its usage of linked lists.

- Lazy or strict? Laziness is more flexible, allowing for things like streaming. Strict strings must be held in memory in their entirety, but can be faster when the whole string would have needed to be computed anyway. Packed lazy representations tend to use chunking to reduce the number of generated thunks. Needless to say, strict strings are the classic interpretation, although lazy strings have useful applications for streaming.

Based on these questions, here are where the string libraries of Hackage fall:

Beyond in-memory encoding, there is also a question of source and target encodings: hopefully something normal, but occasionally you get Shift_JIS text and you need to do something to it. You can convert it to Unicode with encoding (handles String or strict/lazy ByteString with possibility for extension with ByteSource and ByteSink) or iconv (handles strict/lazy ByteString).

Unicode joke.

Well done, mortal! But now thou must face the final Test...--More--

Wizard the Evoker St:10 Dx:14 Co:12 In:16 Wi:11 Ch:12 Chaotic

Dlvl:BMP $:0 HP:11(11) Pw:7(7) AC:9 Xp:1/0 T:1

Alt text. Yeah, I got to the Supplementary Special-purpose Plane, but then I got killed by TAG LATIN CAPITAL LETTER A. It looked like a normal A so I assumed it was just an Archon…

July 30, 2010Taking a page from Raymond Chen’s blog, please post suggestions for future blog posts by me. What would you like to see me explain? What do you think would be amusing if I attempted to write a post about it? Topics I am inclined to cover:

- Almost anything about Haskell, GHC and closely related maths.

- General programming topics.

- Educating, teaching, lecturing.

- Computer science topics of general interest.

- Stories about my internship experiences (at this point, I’ve interned at OmniTI, ITA Software, Ksplice and Galois.)

- SIPB.

- Music.

Since Raymond is famous and I’m not, I will be much less choosy about which suggestions I will post about.

July 28, 2010Today, we talk in more detail at some points about dynamic binding that Dan Doel brought up in the comments of Monday’s post. Our first step is to solidify our definition of dynamic binding as seen in a lazy language (Haskell, using the Reader monad) and in a strict language (Scheme, using a buggy meta-circular evaluator). We then come back to implicit parameters, and ask the question: do implicit parameters perform dynamic binding? (Disregarding the monomorphism restriction, Oleg says no, but with a possible bug in GHC the answer is yes.) And finally, we show how to combine the convenience of implicit parameters with the explicitness of the Reader monad using a standard trick that Oleg uses in his monadic regions.

Aside. For those of you with short attention span, the gist is this: the type of an expression that uses an implicit parameter determines when the binding for the implicit parameter gets resolved. For most projects, implicit parameters will tend to get resolved as soon as possible, which isn’t very dynamic; turning off the monomorphism restriction will result in much more dynamic behavior. You won’t see very many differences if you only set your implicit parameters once and don’t touch them again.

At risk of sounding like a broken record, I would like to review an important distinction about the Reader monad. In the Reader monad, there is a great difference between the following two lines:

do { x <- ask; ... }

let x = ask

If we are in the Reader r monad, the first x would have the type r, while the second x would have the type Reader r r; one might call the second x “delayed”, because we haven’t used >>= to peek into the proverbial monad wrapper and act on its result. We can see what is meant by this in the following code:

main = (`runReaderT` (2 :: Int)) $ do

x <- ask

let m = ask

liftIO $ print x

m3 <- local (const 3) $ do

liftIO $ print x

y <- m

liftIO $ print y

let m2 = ask

return m2

z <- m3

liftIO $ print z

which outputs:

2

2

3

2

Though we changed the underlying environment with the call to local, the original x stayed unchanged, while when we forced the value of m into y, we found the new environment. m2 acted analogously, though in the reverse direction (declared in the inner ReaderT, but took on the outer ReaderT value). The semantics are different, and the syntax is different accordingly.

Please keep this in mind, as we are about to leave the (dare I say “familiar”?) world of monads to the lands of Lisp, where most code is not monadic, where dynamic binding was accidentally invented.

Here, I have the pared-down version of the metacircular evaluator found in SICP (with mutation and sequencing ripped out; the theory is sound if these are added in but we’re ignoring them for the purpose of this post):

(define (eval exp env)

(cond ((self-evaluating? exp) exp)

((variable? exp) (lookup-variable-value exp env))

((lambda? exp)

(make-procedure (lambda-parameters exp)

(lambda-body exp)))

((application? exp)

(apply (eval (operator exp) env)

(list-of-values (operands exp) env))

env)

))

(define (apply procedure arguments env)

(eval

(procedure-body procedure)

(extend-environment

(procedure-parameters procedure)

arguments

env)))

Here’s another version of the evaluator:

(define (eval exp env)

(cond ((self-evaluating? exp) exp)

((variable? exp) (lookup-variable-value exp env))

((lambda? exp)

(make-procedure (lambda-parameters exp)

(lambda-body exp)

env))

((application? exp)

(apply (eval (operator exp) env)

(list-of-values (operands exp) env)))

))

(define (apply procedure arguments)

(eval

(procedure-body procedure)

(extend-environment

(procedure-parameters procedure)

arguments

(procedure-environment procedure))))

If your SICP knowledge is a little rusty, before consulting the source, try to figure out which version implements lexical scoping, and which version implements dynamic scoping.

The principal difference between these two versions lie in the definition of make-procedure. The first version is essentially a verbatim copy of the lambda definition, taking only the parameters and body, while the second adds an extra bit of information, the environment at the time the lambda was made. Conversely, when apply unpacks the procedure to run its innards, the first version needs some extra information—the current environment—to serve as basis for the environment that we will run eval with, while the second version just uses the environment it tucked away in the procedure. For a student who has not had the “double-bubble” lambda-model beaten into their head, both choices seem plausible, and they would probably just go along with the definition of make-procedure (nota bene: giving students an incorrect make-procedure would be very evil!)

The first version is dynamically scoped: if I attempt to reference a variable that is not defined by the lambda’s arguments, I look for it in the environment that is calling the lambda. The second version is lexically scoped: I look for a missing variable in the environment that created the lambda, which happens to be where the lambda’s source code is, as well.

So, what does it mean to “delay” a reference to a variable? If it is lexically scoped, not much: the environment that the procedure is to use is set in stone from the moment it was created, and if the environment is immutable (that is, we disallow set! and friends), it doesn’t matter at all when we attempt to dereference a variable.

On the other hand, if the variable is dynamically scoped, the time when we call the function that references the variable is critical. Since Lisps are strictly evaluated, a plain variable expression will immediately cause a lookup in the current calling environment, but a “thunk” in the form of (lambda () variable) will delay looking up the variable until we force the thunk with (thunk). variable is directly analogous to a value typed r in Haskell, while (lambda () variable) is analogous to a value typed Reader r r.

Back to Haskell, and to implicit parameters. The million dollar question is: can we distinguish between forcing and delaying an implicit parameter? If we attempt a verbatim translation of the original code, we get stuck very quickly:

main = do

let ?x = 2 :: Int

let x = ?x

m = ?x

...

The syntax for implicit parameters doesn’t appear to have any built-in syntax for distinguishing x and m. Thus, one must wonder, what is the default behavior, and can the other way be achieved?

In what is a rarity for Haskell, the types in fact change the semantics of the expression. Consider this annotated version:

main =

let ?x = 2 :: Int

in let x :: Int

x = ?x

m :: (?x :: Int) => Int

m = ?x

in let ?x = 3 :: Int

in print (x, m)

The type of x is Int. Recall that the (?x :: t) constraint indicates that an expression uses that implicit variable. How can this be: aren’t we illegally using an implicit variable when we agreed not to? There is one way out of this dilemma: we force the value of ?x and assign that to x for the rest of time: since we’ve already resolved ?x, there is no need to require it wherever x may be used. Thus, removing the implicit variables from the type constraint of an expression forces the implicit variables in that expression.

m, on the other hand, performs no such specialization: it proclaims that you need ?x in order to use the expression m. Thus, evaluation of the implicit variable is delayed. Keeping an implicit variable in the type constraint delays that variable.

So, if one simply writes let mystery = ?x, what is the type of mystery? Here, the dreaded monomorphism restriction kicks in. You may have seen the monomorphism restriction before: in most cases, it makes your functions less general than you would like them to be. However, this is quite obvious—your program fails to typecheck. Here, whether or not the monomorphism restriction is on will not cause your program to fail typechecking; it will merely change it’s behavior. My recommendation is to not guess, and explicitly specify your type signatures when using implicit parameters. This gives clear visual cues on whether or not the implicit parameter is being forced or delayed.

Aside. For the morbidly curious, if the monomorphism restriction is enabled (as it is by default) and your expression is eligible (if it takes no arguments, it is definitely eligible, otherwise, consult your nearest Haskell report), all implicit parameters will be specialized out of your type, so let mystery = ?x will force ?x immediately. Even if you have carefully written the type for your implicit parameter, a monomorphic lambda or function can also cause your expression to become monomorphic. If the monomorphism restriction is disabled with NoMonomorphismRestriction, the inference algorithm will preserve your implicit parameters, delaying them until they are used in a specialized context without the implicit parameters. GHC also experimentally makes pattern bindings monomorphic, which is tweaked by NoMonoPatBinds.

The story’s not complete, however: I’ve omitted m2 and m3! :

main =

let ?x = (2 :: Int)

in do m3 <- let x :: Int

x = ?x

m :: (?x :: Int) => Int

m = ?x

in let ?x = 3

in let m2 :: (?x :: Int) => Int

m2 = ?x

in print (x, m) >> return m2

print m3

But m3 prints 3 not 2! We’ve specified our full signature, as we were supposed to: what’s gone wrong?

The trouble is, the moment we try to use m2 to pass it out of the inner scope back out to the outer scope, we force the implicit parameter, and the m3 that emerges is nothing more than an m3 :: Int. Even if we try to specify that m3 is supposed to take an implicit parameter ?x, the parameter gets ignored. You can liken it to the following chain:

f :: (?x :: Int) => Int

f = g

g :: Int

g = let ?x = 2 in h

h :: (?x :: Int) => Int

h = ?x

g is monomorphic: no amount of coaxing will make ?x unbound again.

Our brief trip in Scheme-land, however, suggests a possible way to prevent m2 from being used prematurely: put it in a thunk. :

main =

let ?x = (2 :: Int)

in let f2 :: (?x :: Int) => () -> Int

f2 = let ?x = 3

in let f1 :: (?x :: Int) => () -> Int

f1 = \() -> ?x

in f1

in print (f2 ())

But we find that when we run f2 (), the signature goes monomorphic, once again too early. While in Scheme, creating a thunk worked because dynamic binding was intimately related to execution model, in Haskell, implicit parameters are ruled by the types, and the types are not right.

Dan Doel discovered that there is a way to make things work: move the ?x constraint to the right hand side of the signature:

main =

let ?x = (2 :: Int)

in let f2 :: () -> (?x :: Int) => Int

f2 = let ?x = (3 :: Int)

in let f1 :: () -> (?x :: Int) => Int

f1 = \() -> ?x

in f1

in print (f2 ())

In the style of higher ranks, this is very brittle (the slightest touch, such as an id function, can cause the higher-rank to go away). Simon Peyton Jones was surprised by this behavior, so don’t get too attached to it.

Here is another way to get “true” dynamic binding, as well as a monadic interface that, in my opinion, makes bind time much clearer. It is patterned after Oleg’s monadic regions.

{-# LANGUAGE ImplicitParams, NoMonomorphismRestriction,

MultiParamTypeClasses, FlexibleInstances #-}

import Control.Monad

import Control.Monad.Reader

-- How the API looks

f = (`runReaderT` (2 :: Int)) $ do

l1 <- label

let ?f = l1

r1 <- askl ?f

liftIO $ print r1

g

g = (`runReaderT` (3 :: Int)) $ do

l <- label

let ?g = l

r1 <- askl ?f

r2 <- askl ?g

liftIO $ print r1

liftIO $ print r2

delay <- h

-- change our environment before running request

local (const 8) $ do

r <- delay

liftIO $ print r

h = (`runReaderT` (4 :: Int)) $ do

l3 <- label

let ?h = l3

r1 <- askl ?f

r2 <- askl ?g

r3 <- askl ?h

-- save a delayed request to the environment of g

let delay = askl ?g

liftIO $ print r1

liftIO $ print r2

liftIO $ print r3

return delay

-- How the API is implemented

label :: Monad m => m (m ())

label = return (return ())

class (Monad m1, Monad m2) => LiftReader r1 m1 m2 where

askl :: ReaderT r1 m1 () -> m2 r1

instance (Monad m) => LiftReader r m (ReaderT r m) where

askl _ = ask

instance (Monad m) => LiftReader r m (ReaderT r1 (ReaderT r m)) where

askl = lift . askl

instance (Monad m) => LiftReader r m (ReaderT r2 (ReaderT r1 (ReaderT r m))) where

askl = lift . askl

This is a hybrid approach: every time we add a new parameter in the form of a ReaderT monad, we generate a “label” which will allow us to refer back to that monad (this is done by using the type of the label to lift our way back to the original monad). However, instead of passing labels lexically, we stuff them in implicit parameters. There is then a custom askl function, which takes a label as an argument and returns the environment corresponding to that monad. The handle works even if you change the environment with local:

*Main> f

2

2

3

2

3

4

8

Explaining this mechanism in more detail might be the topic of another post; it’s quite handy and very lightweight.

Conclusion. If you plan on using implicit variables as nothing more than glorified static variables that happen to be changeable at runtime near the very top of your program, the monomorphism restriction is your friend. However, to be safe, force all your implicit parameters. You don’t need to worry about the difficulty of letting implicit variables escape through the output of a function.

If you plan on using dynamic scoping for fancier things, you may be better off using Oleg-style dynamic binding and using implicit parameters as a convenient way to pass around labels.

Postscript. Perhaps the fact that explaining the interaction of monomorphism and implicit parameters took so long may be an indication that advanced use of both may not be for the casual programmer.

July 26, 2010For when the Reader monad seems hopelessly clunky

The Reader monad (also known as the Environment monad) and implicit parameters are remarkably similar even though the former is the standard repertoire of a working Haskell programmer while the latter is a GHC language extension used sparingly by those who know about it. Both allow the programmer to code as if they had access to a global environment that can still change at runtime. However, implicit parameters are remarkably well suited for cases when you would have used a stack of reader transformers. Unfortunately, unlike many type system extensions, GHC cannot suggest that you enable ImplicitParams because the code you innocently wrote is not valid Haskell98 but would be valid if you enabled this extension. This post intends to demonstrate one way to discover implicit parameters, with a little nudging.

Reader monad in practice. The Reader monad is really quite simple: after all, it is isomorphic to (->) r, the only real difference being a newtype. Because of this, in engineering contexts, it is rarely used as-is; in particular:

- It is used as a transformer, endowing an “environment” to whatever application-specific monad you are building, and

- It is used with a record type, because an environment of only one primitive value is usually not very interesting.

These choices impose some constraints on how code written for a Reader monad can be used. In particular, baking in the environment type r of ReaderT r means that your monadic code will not play nicely with some other monadic code ReaderT r2 without some coaxing; additionally, I can’t build up a complicated record type Record { field1 :: Int; field2 :: String; field3 :: Bool} incrementally as I find out values of the environment. I could have my record type be a map of some sort, in which case I could place arbitrarily values in it, but in this case I have no static assurances of what values will or will not be in the map at a given point in time.

Stacked Reader transformers. To allow ourselves to incrementally build up our environment, one might consider stacking the Reader monad transformers. Consider the type ReaderT a (ReaderT b (ReaderT c IO)) (). If we desugar this into function application, we find a -> (b -> (c -> IO ())), which can be further simplified to a -> b -> c -> IO (). If a, b and c happen to be the same type, we don’t have any way of distinguishing the different values, except for the location in the list of arguments. However, instead of writing out the parameters explicitly in our function signature (which, indeed, we are trying to avoid with the reader monad), we find ourselves having to lift ask repeatedly (zero times for a, once for b and twice for c). Unlike the record with three fields, there is no name for each environment variable: we have to refer to them by using some number of lifts.

Aside. In fact, this is a De Bruijn index, which Oleg helpfully pointed in out in an email conversation we had after my post about nested loops and continuations. The number of lifts is the index (well, the Wikipedia article is 1-indexed, in which case add one) which tells us how many reader binding scopes we need to pop out of. So if I have:

runReaderT (runReaderT (runReaderT (lift ask) c) b) a

\------- outermost/furthest context (3) ------------/

\--- referenced context (2; one lift) -/

\--- inner context (1) -/

I get the value of b. This turns out to be wonderful for the lambda-calculus theoreticians (who are cackling gleefully at trouble-free α-conversion), but not so wonderful for software engineers, for whom De Bruijn indexes are equivalent to the famous antipattern, the magic number.

With typeclass tricks, we can get back names to some extent: for example, Dan Piponi renames the transformers with singleton data types or “tags”, bringing in the heavy guns of OverlappingInstances in the process. Oleg uses lexical variables that are typed to the layer they belong to to identify different layers, although such an approach is not really useful for a Reader monad stack, since the point of the Reader monad is not to have to pass any lexical variables around, whether or not they are the actual variables or specially typed variables.

Implicit parameters. In many ways, implicit parameters are a cheat: while Dan and Oleg’s approaches leverage existing type-level programming facilities, implicit parameters define a “global” namespace (well known to Lispers as the dynamic scope) that we can stick variables in, and furthermore it extends the type system so we can express what variables in this namespace any given function call expects to exist (without needing to use monads, the moxy!)

Instead of an anonymous environment, we assign the variable a name:

f :: ReaderT r IO a

f' :: (?implicit_r :: r) => IO a

f' is still monadic, but the monad doesn’t express what is in the environment anymore: it’s entirely upon the type signature to determine if an implicit variable is passed along:

f = print "foobar" >> g 42 -- Environment always passed on

f' = print "foobar" >> g 42 -- Not so clear!

Indeed, g could have just as well been a pure computation:

f' = print (g 42)

However, if the type of is:

g :: IO a

the implicit variable is lost, while if it is:

g :: (?implicit_r :: r) => IO a

the variable is available.

While runReader(T) was our method for specifying the environment, we now have a custom let syntax:

runReaderT f value_of_r

let ?implicit_r = value_of_r in f

Besides having ditched our monadic restraints, we can now easily express our incremental environment:

run = let ?implicit_a = a

?implicit_b = b

?implicit_c = c

in h

h :: (?implicit_a :: a, ?implicit_b :: b, ?implicit_c :: c) => b

h = ?implicit_b

You can also use where. Note that, while this looks deceptively like a normal let binding, it is quite different: you can’t mix implicit and normal variable bindings, and if you have similarly named implicit bindings on the right-hand side, they refer to their values outside of the let. No recursion for you! (Recall runReaderT: the values that we supply in the second argument are pure variables and not values in the Reader monad, though with >>= you could instrument things that way.)

Good practices. With monadic structure gone, there are fewer source-level hints on how the monomorphism restriction and polymorphic recursion apply. Non-polymorphic recursion will compile, and cause unexpected results, such as your implicit parameter not changing when you expect it to. You can play things relatively safely by making sure you always supply type signatures with all the implicit parameters you are expecting. I hope to do a follow-up post explaining more carefully what these semantics are, based off of formal description of types in the relevant paper.

July 23, 2010Foreign.ForeignPtr is a magic wand you can wave at C libraries to make them suddenly garbage collected. It’s not quite that simple, but it is pretty darn simple. Here are a few quick tips from the trenches for using foreign pointers effectively with the Haskell FFI:

- Use them as early as possible. As soon as a pointer which you are expected to free is passed to you from a foreign imported function, you should wrap it up in a ForeignPtr before doing anything else: this responsibility lies soundly in the low-level binding. Find the functions that you have to import as

FunPtr. If you’re using c2hs, declare your pointers foreign. - As an exception to the above point, you may need to tread carefully if the C library offers more than one way to free pointers that it passes you; an example would be a function that takes a pointer and destroys it (likely not freeing the memory, but reusing it), and returns a new pointer. If you wrapped it in a ForeignPtr, when it gets garbage collected you will have a double-free on your hands. If this is the primary mode of operation, consider a

ForeignPtr (Ptr a) and a customized free that pokes the outside foreign pointer and then frees the inner pointer. If there is no logical continuity with respect to the pointers it frees, you can use a StablePtr to keep your ForeignPtr from ever being garbage collected, but this is effectively a memory leak. Once a foreign pointer, always a foreign pointer, so if you can’t commit until garbage do us part, don’t use them. - You may pass foreign pointers to user code as opaque references, which can result in the preponderance of newtypes. It is quite useful to define

withOpaqueType so you don’t have to pattern-match and then use withForeignPtr every time your own code peeks inside the black box. - Be careful to use the library’s

free equivalent. While on systems unified by libc, you can probably get away with using free on the int* array you got (because most libraries use malloc under the hood), this code is not portable and will almost assuredly crash if you try compiling on Windows. And, of course, complicated structs may require more complicated deallocation strategies. (This was in fact the only bug that hit me when I tested my own library on Windows, and it was quite frustrating until I remembered Raymond’s blog post.) - If you have pointers to data that is being memory managed by another pointer which is inside a ForeignPtr, extreme care must be taken to prevent freeing the ForeignPtr while you have those pointers lying around. There are several approaches:

- Capture the sub-pointers in a Monad with rank-2 types (see the

ST monad for an example), and require that the monad be run within a withForeignPtr to guarantee that the master pointer stays alive while the sub-pointers are around, and guarantee that the sub-pointer can’t leak out of the context. - Do funny things with

Foreign.ForeignPtr.Concurrent, which allows you to use Haskell code as finalizers: reference counting and dependency tracking (only so long as your finalizer is content with being run after the master finalizer) are possible. I find this very unsatisfying, and the guarantees you can get are not always very good.

- If you don’t need to release a pointer into the wild, don’t! Simon Marlow acknowledges that finalizers can lead to all sorts of pain, and if you can get away with giving users only a bracketing function, you should consider it. Your memory usage and object lifetime will be far more predictable.

July 21, 2010Attention conservation notice. Function pipelines offer an intuitive way to think about continuations: continuation-passing style merely reifies the pipeline. If you know continuations, this post probably won’t give you much; otherwise, I hope this is an interesting new way to look at them. Why do you care about continuations? They are frequently an extremely fast way to implement algorithms, since they are essentially pure (pipeline) flow control.

In Real World Haskell, an interesting pattern that recurs in functional programs that use function composition (.) is named: pipelining. It comes in several guises: Lispers may know it as the “how many closing parentheses did I need?” syndrome:

(cons 2 (cdr (cdr (car (car x)))))

Haskellers may see it in many forms: the parenthesized:

sum (map (+2) (toList (transform inputMap)))

or the march of dollar signs:

sum $ map (+2) $ toList $ transform inputMap

or perhaps the higher-order composition operator (as is suggested good style by several denizens of #haskell):

sum . map (+2) . toList . transform $ inputMap

There is something lexically interesting about this final form: the $ has divided it into two tokens, a function and an input argument. I can copy paste the left side and insert it into another pipeline effortlessly (compare with the parentheses, where after the paste occurs I have to manually insert the missing closing parentheses). The function is also a first class value, and I can write it in point-free style and assign it to a variable.

Of course, if I want to move it around, I have to cut and paste it. If I want to split it up into little parts, I have to pull a part the dots with my keyboard. If I want to use one pipeline in one situation, and another pipeline in a different one, I’d have to decide which situation I was in at the time of writing the program. Wouldn’t it be nice if a program could do it for me at runtime? Wink.

Consider the following pipeline in a Lisp-like language:

(h (g (f expr)))

When we refer to the “continuation” of expr there is frequently some attempt of visualizing the entire pipeline with expr removed, a hole in its place. This is the continuation:

(h (g (f ____)))

As far as visuals go, it could be worse. Since a continuation is actually a function, to be truly accurate we should write something horribly uninstructive along these lines:

(lambda (x) (h (g (f x))))

But this is good: it precisely captures what the continuation is, and is amenable to a more concise form. Namely, this can be written in Haskell point-free as:

h . g . f

So the continuation is just the pipeline to the left of the expression!

A little more detail, a lot more plumbing. There are two confounding factors in most treatments of continuations:

- They’re not written in a pure language, and a sequential series of actions is not immediately amenable to pipelining (although, with the power of monads, we can make it so), and

- The examples I have given still involve copy-paste: by copy-pasting, I have glossed over some details. How does the program know that the current continuation is

h . g . f? In callCC, how does it know when the current continuation got called?

For reference, here is an implementation of the Cont monad:

newtype Cont r a = Cont { runCont :: (a -> r) -> r }

instance Monad (Cont r) where

return x = Cont (\k -> k x)

(Cont c) >>= f = Cont (\k -> c (\r -> runCont (f r) k))

Where’d my nice pipelines go? I see a lot of lambdas… perhaps the Functor instance will give more clues:

instance Functor (Cont r) where

fmap f = \c -> Cont (\k -> runCont c (k . f))

That little composition operator should stand out: it states the essence of this Functor definition. The rest is just plumbing. Namely, when we lift some regular function (or pipeline) into the continuation monad, we have added the ability to compose arbitrary functions to the left end of it. That is, k . g . f, where k is my added function (the continuation). In more detail, from:

g . f

to:

\k -> k . (g . f)

or, with points:

\x k -> (k . g . f $ x)

Now there is a puzzle: suppose I have a function h. If I were not in continuation land, I could combine that with g . f as h . g . f. But if both are in continuation land: \k1 -> k1 . (g . f) and k2 -> k2 . h, how do I compose them now?

k1 is in the spot where I normally would have placed h, so a first would be to apply the first lifted function with the second lifted function as it’s argument:

\k1 -> k1 . (g . f) $ \k2 -> k2 . h

(\k2 -> k2 . h) . (g . f)

That doesn’t quite do it; the lambda closes its parentheses too early. We wanted:

\k2 -> k2 . h . (g . f)

With a little more head-scratching (left as an exercise to the reader), we find the correct form is:

\k -> (\k1 -> k1 . (g . f)) (\r -> (\k2 -> k2 . h) k r)

\-- 1st lifted fn --/ \-- 2nd fn --/

This is the essential mind-twisting flavor of continuation passing style, and the reader will notice that we had to introduce two new lambdas to make the kit and kaboodle run (reminiscent of our Monad instance). This is the ugly/elegant innards of the Continuation monad. There is, afterwards, the essential matter of newtype wrapping and unwrapping, and the fact that this implements Kleisli arrow composition ((a -> m b) -> (b -> m c) -> a -> m c, not bind m a -> (a -> m b) -> m b. All left as an exercise to the reader! (Don’t you feel lucky.)

Our final topic is callCC, the traditional method of generating interesting instances of continuations. The essential character of plain old functions in the Cont monad are that they “don’t know where they are going.” Notice in all of our examples we’ve posited the ability to compose a function on the left side k, but not actually specified what that function is: it’s just an argument in our lambda. This gives rise to the notion of a default, implicit continuation: if you don’t know where you’re going, here’s a place to go. The monadic code you might write in the Cont monad is complicit in determining these implicit continuations, and when you run a continuation monad to get a result, you have to tell it where to go at the very end.

callCC makes available a spicy function (the current continuation), which knows where it’s going. We still pass it a value for k (the implicit continuation), in case it was a plain old function, but the current continuation ignores it. Functions in the continuation monad no longer have to follow the prim and proper \k -> k . f recipe. callCC’s definition is as follows:

callCC f = Cont (\k -> runCont (f (\x -> Cont (\_ -> k a))) k)

The spicy function is \x -> Cont (\_ -> k x) (without the wrapping, it’s \x _ -> k x), which, as we can see, ignores the local current continuation (which corresponds to wherever this function was called) and uses k from the outer context instead. k was the current continuation at the time of callCC.

A parallel (though imperfect) can be made with pipelines: consider a pipeline where I would like the last function in the pipeline to be one type of function on a success, and another on failure:

\succ fail -> either fail succ . h . g . f

This pipeline has two outcomes, success:

\succ _ -> succ . fromRight . h . g . f

or failure:

\_ fail -> fail . fromLeft . h . g . f

In each case, the other continuation is ignored. The key for callCC is that, while it’s obvious how to ignore explicit continuations, it requires a little bit of thought to figure out how to ignore an implicit continuation. But callCC generates continuations that do just that, and can be used anywhere in the continuation monad (you just have to figure out how to get them there: returning it from the callCC or using the ContT transformer on a monad with state are all ways of doing so).

Note. The Logic monad uses success (SK) and failure (FK) continuations without the Cont monad to implement backtracking search, demonstrating that continuation passing style can exist without the Cont monad, and can frequently be clearer that way if you derive no benefits from having a default implicit continuation. It is no coincidence that Cont and callCC are particularly well suited for escape operations.

July 19, 2010System.Posix.Redirect is a Haskell implementation of a well-known, clever and effective POSIX hack. It’s also completely fails software engineering standards. About a week ago, I excised this failed experiment from my work code and uploaded it to Hackage for strictly academic purposes.

What does it do? When you run a command in a shell script, you have the option of redirecting its output to another file or program:

$ echo "foo\n" > foo-file

$ cat foo-file

foo

$ cat foo-file | grep oo

foo

Many APIs for creating new processes which allow custom stdin/stdout/stderr handles exist; what System.Posix.Redirect lets you do is redirect stdout/stderr without having to create a new process:

redirectStdout $ print "foo"

How does it do it? On POSIX systems, it turns out, almost exactly the same thing that happens when you create a subprocess. We can get a hint by strace’ing a process that creates a subprocess with slightly different handles. Consider this simple Haskell program:

import System.Process

import System.IO

main = do

-- redirect stdout to stderr

h <- runProcess "/bin/echo" ["foobar"] Nothing Nothing Nothing (Just stderr) Nothing

waitForProcess h

When we run strace -f (the -f flag to enable tracking of subprocesses), we see:

vfork(Process 26861 attached

) = 26861

[pid 26860] rt_sigprocmask(SIG_SETMASK, [], NULL, 8) = 0

[pid 26860] ioctl(0, SNDCTL_TMR_TIMEBASE or TCGETS, {B38400 opost isig icanon echo ...}) = 0

[pid 26860] ioctl(1, SNDCTL_TMR_TIMEBASE or TCGETS, {B38400 opost isig icanon echo ...}) = 0

[pid 26860] waitpid(26861, Process 26860 suspended

<unfinished ...>

[pid 26861] rt_sigprocmask(SIG_SETMASK, [], NULL, 8) = 0

[pid 26861] dup2(0, 0) = 0

[pid 26861] dup2(2, 1) = 1

[pid 26861] dup2(2, 2) = 2

[pid 26861] execve("/bin/echo", ["/bin/echo", "foobar"], [/* 53 vars */]) = 0

The dup2 calls are the key, since there are no special arguments to be passed to vfork or execve (the “53 vars” are the inherited environment) to fiddle with the standard handles of the subprocess, we need to fix them ourself. dup2 copies the file descriptor 2, guaranteed to be stderr (0 is stdin, and 1 is stdout), onto stdout, which is what we asked for in the original code. File descriptor tables are global to a process, so when we change the file descriptor 1, everyone notices.

There is one complication when we are not planning on following up the dup2 call with an execve: your standard library may be buffering output, in which case there might have been some data still living in your program that hasn’t been written to the file descriptor. If you play this trick in a normal POSIX C application, you only need to flush the FILE handles from stdio.h. If you’re in a Haskell application, you also need to flush Haskell’s buffers. (Notice that this isn’t necessary if you execve, since this system call blows away the memory space for the new program.)

Why did I write it? I had a very specific use-case in mind when I wrote this module: I had an external library written in C that wrote error conditions to standard output. Imagine a hPutStr that printed an error message if it wasn’t able to write the string, rather than raising an IOException; this would mean terrible things for client code that wanted to catch and handle the error condition. Temporarily redirecting standard output before calling these functions means that I can marshal these error conditions to Haskell while avoiding having to patch the external library or having to relegate it to a subprocess (which would cause much slower interprocess communication).

Why should I not use it in production? “It doesn’t work on Windows!” This is not 100% true: you could get a variant of this to work in some cases.

The primary problem is the prolific selection of runtimes and standard libraries available on Windows. Through some stroke of luck, the vast majority of applications written for Unix use a single standard library: libc, and you can be reasonably certain that you and your cohorts are using a single FILE abstraction, and since file descriptors are kernel-side, they’re guaranteed to work no matter what library you’re using. No such luxury on Windows: that DLL you’re linking against probably was compiled by some other compiler toolchain with it’s own runtime. GHC, in particular, uses the MingW toolchain to link on Windows, whereas native code is much more likely to have been compiled with Microsoft tools (MSVC++, anyone?). If the library could be recompiled with MingW, it could have worked, but I decided that it would be easier to just patch the library to return error codes another way. And so this module was obliterated from the codebase.

July 16, 2010Last Monday, I presented a parallel algorithm for computing maximum weighted matching, and noted that on real hardware, a naive implementation would deadlock.

Several readers correctly identified that sorting the nodes on their most weighted vertex only once was insufficient: when a node becomes paired as is removed from the pool of unpaired nodes, it could drastically affect the sort. Keeping the nodes in a priority queue was suggested as an answer, which is certainly a good answer, though not the one that Feo ended up using.

Feo’s solution. Assign every node an “is being processed bit.” When a node attempts to read its neighbor’s full/empty bit and finds the bit empty, check if the node is being processed. If it is not, atomically check and set the “is being processed bit” to 1 and process the node recursively. Fizzle threads that are scheduled but whose nodes are already being processed. The overhead is one bit per node.

I think this is a particularly elegant solution, because it shows how recursion lets work easily allocate itself to threads that would otherwise be idle.