August 23, 2010Punning is the lowest form of humor. And an endless source of bugs.

The imperative. In programming, semantically different data may have the same representation (type). Use of this data requires manually keeping track of what the extra information about the data that may be in a variable. This is dangerous when the alternative interpretation is right most of the time; programmers who do not fully understand all of the extra conditions are lulled into a sense of security and may write code that seems to work, but actually has subtle bugs. Here are some real world examples where it is particularly easy to confuse semantics.

Variables and literals. The following is a space efficient representation of boolean variables (x, y, z) and boolean literals (x or not x). Boolean variables are simply counted up from zero, but boolean literals are shifted left and least significant bit is used to store complement information. :

int Gia_Var2Lit( int Var, int fCompl ) { return Var + Var + fCompl; }

int Gia_Lit2Var( int Lit ) { return Lit >> 1; }

Consider, then, the following function:

int Gia_ManHashMux( Gia_Man_t * p, int iCtrl, int iData1, int iData0 )

It is not immediately obvious whether or not the iCtrl, iData1 and iData0 arguments correspond to literals or variables: only an understanding of what this function does (it makes no sense to disallow muxes with complemented inputs) or an inspection of the function body is able to resolve the question for certain (the body calls Gia_LitNot). Fortunately, due to the shift misinterpreting a literal as a variable (or vice versa) will usually result in a spectacular error. (Source: ABC)

Pointer bits. It is well known that the lower two bits of a pointer are usually unused: on a 32-bit system, 32-bit integers are the finest granularity of alignment, which force any reasonable memory address to be divisible by four. Space efficient representations may use these two extra bits to store extra information but need to mask out the bits when dereferencing the pointer. Building on our previous example, consider a pointer representation of variables and literals: if a vanilla pointer indicates a variable, then we can use the lowest bit to indicate whether or not the variable is complemented or not, to achieve a literal representation.

Consider the following function:

Gia_Obj_t * Gia_ObjFanin0( Gia_Obj_t * pObj );

where iDiff0 is an int field in the Gia_Obj_t struct. It is not clear whether or not the input pointer or the output pointer may be complemented or not. In fact, the input pointer must not be complemented and the output pointer will never be complemented.

Misinterpreting the output pointer as possibly complemented may seem harmless at first: all that happens is the lower two bits are masked out, which is a no-op on a normal pointer. However, it is actually a critical logic bug: it assumes that the returned pointer’s LSB says anything about whether or not the fanin was complemented, when in fact the returned bit will always be zero. (Source: ABC)

Physical and virtual memory. One of the steps on the road to building an operating system is memory management. When implementing this, a key distinction is the difference between physical memory (what actually is on the hardware) and virtual memory (which your MMU translates from). The following code comes from a toy operating system skeleton that students build upon:

/* This macro takes a kernel virtual address -- an address that points above

* KERNBASE, where the machine's maximum 256MB of physical memory is mapped --

* and returns the corresponding physical address. It panics if you pass it a

* non-kernel virtual address.

*/

#define PADDR(kva) \

({ \

physaddr_t __m_kva = (physaddr_t) (kva); \

if (__m_kva < KERNBASE) \

panic("PADDR called with invalid kva %08lx", __m_kva);\

__m_kva - KERNBASE; \

})

/* This macro takes a physical address and returns the corresponding kernel

* virtual address. It panics if you pass an invalid physical address. */

#define KADDR(pa) \

({ \

physaddr_t __m_pa = (pa); \

uint32_t __m_ppn = PPN(__m_pa); \

if (__m_ppn >= npage) \

panic("KADDR called with invalid pa %08lx", __m_pa);\

(void*) (__m_pa + KERNBASE); \

})

Note that though the code distinguishes with a type synonym uintptr_t (virtual addresses) from physaddr_t (physical addresses), the compiler will not stop the student from mixing the two up. (Source: JOS)

String encoding. Given an arbitrary sequence of bytes, there is no canonical interpretation of what the bytes are supposed to mean in human language. A decoder determines what the bytes probably mean (from out-of-band data like HTTP headers, or in-band data like meta tags) and then converts a byte stream into a more structured internal memory representation (in the case of Java, UTF-16). However, in many cases, the original byte sequence was the most efficient representation of the data: consider the space-difference between UTF-8 and UCS-32 for Latin text. This encourages developers to use native bytestrings to pass data around (PHP’s string type is just a bytestring), but has caused endless headaches if the appropriate encoding is not also kept track of. This is further exacerbated by the existence of Unicode normalization forms, which preclude meaningful equality checks between Unicode strings that may not be in the same normalization form (or may be completely un-normalized).

Endianness. Given four bytes corresponding to a 32-bit integer, there is no canonical “number” value that you may assign to the bytes: what number you get out is dependent on the endianness of your system. The sequence of bytes 0A 0B 0C 0D may be interpreted as 0x0A0B0C0D (big endian) or 0x0D0C0B0A (little endian).

Data validation. Given a data structure representing a human, with fields such as “Real name”, “Email address” and “Phone number”, there are two distinct interpretations that you may have of the data: the data is trusted to be correct and may be used to directly perform an operation such as send an email, or the data is unvalidated and cannot be trusted until it is processed. The programmer must remember what status the data has, or force a particular representation to never contain unvalidated data. “Taint” is a language feature that dynamically tracks the validated/unvalidated status of this data.

The kata. Whenever a data structure (whether simple or complex) could be interpreted multiple ways, newtype it once for each interpretation. :

newtype GiaLit = GiaLit { unGiaLit :: CInt }

newtype GiaVar = GiaVar { unGiaVar :: CInt }

-- accessor functions omitted for brevity; they should be included

newtype CoGia_Obj_t = CoGia_Obj_t (Gia_Obj_t)

newtype PhysAddr a = PhysAddr (Ptr a)

newtype VirtualAddr a = VirtualAddr (Ptr a)

newtype RawBytestring = RawBytestring ByteString

-- where e is some Encoding

newtype EncodedBytestring e = EncodedBytestring ByteString

-- where n is some Normalization

newtype UTF8Bytestring n = UTF8Bytestring ByteString

type Text = UTF8Bytestring NFC

-- where e is some endianness

newtype EndianByteStream e = EndianByteStream ByteString

newtype Tainted c = Tainted c

newtype Clean c = Clean c

Identifying when data may have multiple interpretations may not be immediately obvious. If you are dealing with underlying representations you did not create, look carefully at variable naming and functions that appear to interconvert between the same type. If you are designing a high-performance data structure, identify your primitive data types (which are distinct from int, char, bool, the primitives of a general purpose programming language.) Multiple interpretations can creep in over time as new features are added to code: be willing to refactor (possibly breaking API compatibility) or speculatively newtype important user-visible data.

A common complaint about newtypes is the wrapping and unwrapping of the type. While some of this is a necessary evil, it should not be ordinarily necessary for end-users to wrap and unwrap the newtypes: the internal representation should stay hidden! (This is a closely related but orthogonal property that newtypes help enforce.) Try not to export newtype constructors; instead, export smart constructors and destructors that do runtime sanity checks and are prefixed with unsafe.

When an underlying value is wrapped in the newtype, you are indicating to the compiler that you believe that the value has a meaningful interpretation under that newtype: do your homework when you wrap something! Conversely, you should assume that an incoming newtype has the appropriate invariants (it’s a valid UTF-8 string, its least significant bit is zero, etc.) implied by that newtype: let the static type checker do that work for you! Newtypes have no runtime overhead: they are strictly checked at compile time.

Applicability. A newtype is no substitute for an appropriate data structure: don’t attempt to do DOM transformations over a bytestring of HTML. Newtypes can be useful even when there is only one interpretation of the underlying representation—however, the immediate benefit derives primarily from encapsulation. However, newtypes are essential when there are multiple interpretations of a representation: don’t leave home without them!

August 20, 2010It’s 9:00AM, and the cell phone next to my pillow is vibrating ominously. I rise and dismiss the alarm before it starts ringing in earnest and peek out the window of my room.

Portland summer is a fickle thing: the weather of the first month of my internship was marked by mist and rain (a phenomenon, Don tells me, which is highly unusual for Portland), while the weather of the second month was a sleepy gray in the mornings. “Is it summer yet?” was the topic of #galois for most of July. But in the heart of August, summer has finally arrived, and the sun greets my gaze. Shorts and a T-shirt, no sweater necessary! I silently go “Yes!”

I finish getting dressed, say goodbye to Pixie, the white cat who is curled up in my desk chair, skip breakfast, grab my bike, and head off in the direction of downtown Portland. (Warning: The rest of this post is similarly free of any sort of technical details (except at the very end)! Also, I’m a pretty terrible photographer with no idea how to post-process images.)

Commuting. I bike to work every day. The ride is about 30 minutes.

Along the way, I cross the Willamette:

This is a double-decker bridge, and the bottom platform lifts up when boats need to pass through. Which, unfortunately, is occasionally during my morning commute, in which case I have to bike further down the Riverside Esplanade.

At the end of my journey, I am greeted with the familiar face of the Commonwealth Building.

It’s a pretty famous building as far as buildings go: it was one of the first glass skyscrapers ever built. I hear architecture students from universities around the city come by to look at the building.

Galois is on the third floor.

I park my bike in one of the handy bikeracks in the office:

and head off to my desk. (Crazy deskmate included. :-)

Office. Now that we’re at Galois, perhaps it’s time for a quick tour of the office. The Galois office is a single floor, with various rooms of note. Of ever-present importance is the kitchen:

from which coffee can be acquired (Portlanders are very serious about their coffee! It makes me almost wish that I was a coffee-drinker):

The kitchen is where the all-hands meeting takes place (Galois is small enough that you can fit all of the company’s employees in a single room—only Ksplice, the startup I interned at, has also earned this distinction). One of the really good reflections on Galois’ culture is the practice of appreciations, during which Galwegians (our name for Galois employees) appreciate one another for things that happened during the week.

There is a small library (a nice quiet place to chill out if some particularly hard thinking is merited):

A conference room:

And even a little room where you can take a nap!

By twelve, we Galwegians are hungry, so we head out to get lunch.

There is one tremendous advantage to being in downtown Portland: the food carts. I’ve never seen anything quite like it: blocks literally have fleets of carts lined up to serve you, whatever style of food you like.

Portland is also famously vegan friendly. You can get Vegan Bacon Cheeseburgers! (They are quite delicious, speaking as a carnivore.)

Or a fruit smoothie.

After we get our food, it’s back to the office to chow down.

Our chief scientist and the engineer who sits across from me are having a post-lunch game of ping pong! (I’ve played a few rounds: they are quite good—back spin, top spin, it’s more than I can keep track of!)

Offer building. On Tuesdays, instead of converging on the kitchen, many of converge to the conference room: it’s the MOB lunch!

MOB stands for “Merged Offer Building”, though the name itself has a nice flavor: “The MOB makes you an offer you can’t refuse.” Unlike traditional product companies, in which you have an engineering department which makes a product and then a sales department who finds clients and convinces them they want to buy your product, at Galois, for many contracts the engineers are the salespeople: they are the ones responsible for writing the proposal we submit for funding. The MOB meeting coordinates all of the various offer building efforts—though it’s had no direct bearing to my internship, sitting in on MOB lunches has been a fascinating peek into the world of SBIRs, procurements, EC&A and many, many more acronyms.

tl;dr Interning at Galois this summer has been a blast, and I’m very sorry that there is only one week left. I’ll miss all of you! ♥

Postscript. After a summer of Tech Talk writeups, I’ll be giving a Galois Tech Talk myself, this coming Tuesday! It will get into the nitty gritty of abcBridge, the Haskell library I built over the summer. If you’re in the area, come check it out!

August 18, 2010The imperative. Mutable data structures with many children frequently force any given child to be associated with one given parent data structure:

class DOMNode {

private DOMDocument $ownerDocument;

// ...

public void appendNode(DOMNode n) {

if (n.ownerDocument != this.ownerDocument) {

throw DOMException("Cannot append node that "

"does not belong to this document");

}

// ...

}

}

Client code must be careful not to mix up children that belong to different owners. An object can be copied from one owner to another via a special function. :

class DOMDocument {

public DOMNode importNode(DOMNode node) {

// ...

}

}

Sometimes, a function of this style can only be called in special circumstances. If a mutable data structure is copied, and you would like to reference to a child in the new structure but you only have a reference to its original, an implementation may let you forward such a pointer, but only if the destination structure was the most recent copy. :

class DOMNode {

private DOMNode $copy;

}

The kata. Phantom types in the style of the ST monad permit statically enforced separation of children from different monadic owners. :

{-# LANGUAGE Rank2Types #-}

-- s is the phantom type

newtype DOM s a = ...

newtype Node s = ...

runDom :: (forall s. DOM s ()) -> Document

getNodeById :: Id -> DOM s (Node s)

deleteNode :: Node s -> DOM s ()

-- Does not typecheck, the second runDom uses a fresh

-- phantom variable which does not match node's

runDom $ do

node <- getNodeById "myNode"

let alternateDocument = runDom $ do

deleteNode node

To permit a value of any monad to be used in another monad, implement a function that is polymorphic in both phantom types:

importNode :: Node s -> DOM s2 (Node s2)

setRoot :: Node s -> DOM s ()

-- This now typechecks

runDom $ do

node <- getNodeById "myNode"

let alternateDocument = runDom $ do

node' <- importNode node

setRoot node'

The function will probably be monadic, because the implementation will need to know what owner the Node is being converted to.

To only permit translation under certain circumstances, use a type constructor (you can get these using empty data declarations) on the phantom type:

{-# LANGUAGE EmptyDataDecls #-}

data Dup n

getNewNode :: Node s -> DOM (Dup s) (Node (Dup s))

dupDom :: DOM s () -> DOM s (DOM (Dup s) ())

-- This typechecks, and does not recopy the original node

runDom $ do

node <- getNodeById "myNode"

dupDom $ do

node' <- getNewNode node

...

Applicability. Practitioners of Haskell are encouraged to implement and use pure data structures, where sharing renders this careful book-keeping of ownership unnecessary. Nevertheless, this technique can be useful when you are interfacing via the FFI with a library that requires these invariants.

August 16, 2010What I did for my summer internship at Galois

World of algebra quizzes. As a high schooler, I was using concepts from computer science long before I even knew what computer science was. I can recall taking a math quiz—calculators banned—facing a difficult task: the multiplication of large numbers. I was (and still am) very sloppy when it came to pencil-and-paper arithmetic—if I didn’t check my answers, I would invariably lose points because of “stupid mistakes.” Fortunately, I knew the following trick: if I summed together the digits of my factors (re-summing if the result was ten or more), the product of these two numbers should match the sum of the digits of the result. If not, I knew I had the wrong answer. It wasn’t until much later that I discovered that this was a very rudimentary form of the checksum.

In fact, most of the tricks I rediscovered were motivated by a simple academic need: Was my answer correct or not? Indeed, while I didn’t know it at the time, this question would become the fundamental basis for my internship at Galois this summer.

At about the time I started learning algebra, I began to notice that my tricks for checking arithmetic had become insufficient. If a teacher asked me to calculate the expanded form of the polynomial (x + 2)(x - 3)(x - 5), I had to carry out multiple arithmetic steps before I arrived at an answer. Checking each step was tedious and prone to error—I knew too well that I would probably be blind to errors in the work I had just written. I wanted a different way to check that my answer was correct.

Eventually, I realized that all I had to do was pick a value of x and substitute it into the original question and the answer x³ - 6x² - x + 30. If the values matched, I would be fairly confident in my answer. I also realized that if I picked a number like x = -2, I wouldn’t even have to calculate the value of the original problem: the answer was obviously zero! I had “invented” unit testing, and at the hand of this technique, many symbolic expressions bent to my pencil. (I independently learned about unit testing as a teething programmer, but since a PHP programmer never codes very much math, I never made the connection.)

World of practical software testing. Here, we pass from the world of algebra quizzes to the world of software testing. The expressions being tested are more complicated than x³ - 6x² - x + 30, but most people still adopt the strategy of the high school me: they hand pick a few inputs to test that will give them reasonable confidence that their new implementation is correct. How does one know that the output of the program is the correct one? For many simple programs, the functionality being tested is simple enough that the tester mentally “knows” what the correct result is, and write it down manually—akin to picking inputs like x = -2 that are particularly easy for a human to infer the answer to. For more complex programs, a tester may use a reference implementation to figure out what the expected behavior is supposed to be.

Testing like this can only show the presence of bugs, not the absence of them. But, as many software companies have discovered, this is good enough! If the programmer misses an important test case and a bug report comes in, he fixes the bug and adds a regression test to deal with that buggy input. So, as pragmatists, we have settled for this state of affairs: manual case-by-case testing (which hopefully is automated). The state of the art of conventional software testing is fundamentally the same as how a high-schooler checks his answers on an algebra quiz. Anything better lies beyond the dragons of theoretical computer science research.

Aside. As anyone who has written automated tests before can attest, automated tests are characterized by two primary chores: getting your code to be automatically testable in the first place (much easier if it’s arithmetic than if it’s a kernel driver) and coming up with interesting situations to test your code in. For the latter, it turns out that while humans can come up with decent edge-cases, they’re really bad at coming up with random test-cases. Thus, some extremely practical high-tech testing techniques involve having a computer generate random inputs. Fuzz testing and QuickCheck style testing are both characterized by this methodology, though fuzz testing prides itself in nonsensical inputs, while QuickCheck tries hard to generate sensible inputs.

World of theoretical computer science. The teacher grading your algebra quiz doesn’t do something so simple as pick a few random numbers, substitute them into your answer, and see if she gets the right answer. Instead, she compares your answer (the program itself) against the one she has in the answer key (a reference implementation), and marks you correct if she is able to judge that the answers are the same. If you phrase your answer in terms of Fermat’s last theorem, she’ll mark you off for being cheeky.

The reference implementation may be wrong (bug in the answer key), but in this case it’s our best metric for whether or not a program is “correct.” Since we’ve wandered into the land of theoretical computer science, we might ask this question to the Literal Genie: Is it possible, in general, to determine if two programs are equivalent? The Literal Genie responds, “No!” The question is undecidable: there is no algorithm that can answer this question for all inputs. If you could determine if two programs were equivalent, you could solve the halting problem (the canonical example of an unsolvable problem): just check if a program was equivalent to an infinitely looping one.

While the working theoretician may tame uncountably huge infinities on a regular basis, for a working programmer, the quantities handled on a regular basis are very much finite—the size of their machine integer, the amount of memory on their system, the amount of time a program is allowed to run. When you deal with infinity, all sorts of strange results appear. For example, Rice’s theorem states that figuring out whether or not a program has any non-trivial property (that is, there exists some program that has the property and some program that doesn’t) is undecidable! If we impose some reasonable constraints, such as “the program terminates in polynomial time for all inputs”, the answer to this question is yes! But can we do so in a way that is better than testing that the programs do the same thing on every input?

World of more practical computer science. We’ve relinquished enough theoretical purity to make our question interesting again for software engineers, but it is still very difficult for the programmer to prove to himself that the algorithm is equivalent to his reference implementation. In contrast, it’s easy for a user to show that the algorithm is wrong: all they have to do is give the programmer an input for which his implementation and the reference implementation disagree.

Computer scientists have a name for this situation: problems for which you can verify their solutions (in this case, more of an anti-solution: a counter-example) in polynomial time are NP. Even if both programs run in constant time, as a combinational logic circuit might (to simulate such a circuit, we only need to propagate the inputs through as many gates as they are in the circuit: there is no dependence on the input), it still takes exponential time to brute-force an equivalence check. Every time we add another bit to the input, we double the amount of possible inputs to check.

In fact, the question of circuit non-equivalence is NP-complete. We’ve been talking about program equivalence, but we can also talk about problem equivalence, for which you can translate one problem (graph coloring) into another one (traveling salesman). In the seventies, computer scientists spent a lot of time proving that a lot of problems that required “brute force” were actually all the same problem. Stephen Cook introduced the idea that there were problems that were NP-complete: problems in NP for which we could translate all other problems in NP into. The most famous example of an NP-complete problem is SAT, in which given a logical formula with boolean variables, you ask whether or not there is a satisfying assignment of variables, variables that will cause this formula to be true.

To show that circuit non-equivalence is NP-complete, we need to show that it is in NP (which we’ve done already) and show that we can translate some other NP-complete problem into this problem. This is quite easy to do with SAT: write a program that takes the boolean variables of SAT as inputs and outputs the result of the logical formula and then see if it’s equivalent to a program that always returns false.

The other direction is only slightly less trivial, but important practically speaking: if we can reduce our problem into an instance of SAT, I can chuck it a highly optimized SAT solver. A satisfiability problem is isomorphic to a logic circuit that outputs a single bit. We can translate a circuit equivalence problem into SAT by combining the circuits into what is called a “miter”: we combine the inputs of the two original logic circuits into a single set that feeds into both circuits, and then test the corresponding output bits between the two circuits for equality (XOR), ORing the entire result together. The resulting circuit outputs 0 if the outputs were the same between the two circuits (all of the XORs returned 0), and outputs 1 if there is a mismatch.

“Great,” you may be thinking, “but I’m a programmer, not a hardware designer. Most of my programs can’t be expressed just in terms of logic gates!” That is true: to encode state, you also need latches, and input/output needs to be simulated with special input and output “ports”. However, there are many important problems that are purely combinational: the shining example of which is cryptography, which protects your money, employs a lot of complicated math and is ruthlessly optimized.

But there still is one standing complaint: even if my programs are just logic circuits, I wouldn’t want to write them in terms of ANDs, ORs and NOTs. That just seems painful!

Enter Cryptol, the project that I am working on at Galois. Cryptol bills itself as follows:

Cryptol is a language for writing specifications for cryptographic algorithms. It is also a tool set for producing high-assurance, efficient implementations in VHDL, C, and Haskell. The Cryptol tools include the ability to equivalence check the reference specification against an implementation, whether or not it was compiled from the specifications.

But what really makes it notable, in my humble intern opinion, is the fact that it can take programs written in programming languages like C, VHDL or Cryptol and convert them into logic circuits, or, as we call them, “formal models”, which you can chuck at a SAT solver which will do something more sensible than brute-force all possible inputs. At one point, I thought to myself, “It’s a wonder that Cryptol even works at all!” But it does, and remarkably well for its problem domain of cryptographic algorithms. The state of the art in conventional software testing is manually written tests that can only show the presence of bugs in an implementation; the state of the art in Cryptol is a fully automatic test that gives assurance that an implementation has no bugs. (Of course, Cryptol could be buggy, but such is the life of high assurance.)

SAT solvers are perhaps one of the most under-utilized high-tech tools that a programmer has at their fingertips. An industrial strength SAT solver can solve most NP-complete problems in time for lunch, and there are many, many problems in NP with wide-ranging practical applications. However, the usual roadblocks to using a SAT solver include:

- No easy way to translate your problem into SAT and then run it on one of the highly optimized solvers, which are frequently poorly documented, library-unfriendly projects in academia,

- Generating friendly error messages when your SAT solver passes or fails (depending on what is an “error”), and

- Convincing your team that, no really, you want a SAT solver (instead of building your own, probably not-as-efficient implementation.)

My primary project was addressing issue one, in Haskell, by building a set of bindings for ABC, a System for Sequential Synthesis and Verification called abcBridge. One might observe that Haskell already has a number of SAT solving libraries: ABC is notable because it employs an alternative formulation of SAT in the form of And-Inverter Graphs (NAND gates are capable of simulating all boolean logic) as well as some novel technology for handling AIGs such as fraiging, which is a high-level strategy that looks for functionally equivalent subsets of your circuits.

The project itself has been a lot of fun: since I was building this library from scratch, I had a lot of flexibility with API decisions, but at the same time got my hands into the Cryptol codebase, which I needed to integrate my bindings with. With any luck, we’ll be releasing the code as open source at the end of my internship. But I’m going to miss a lot more than my project when my internship ends in two weeks. I hope to follow up with a non-technical post about my internship. Stay tuned!

Post factum. Hey, this is my hundredth post. Sweet!

August 13, 2010Edit. ddarius pointed out to me that the type families examples were backwards, so I’ve flipped them to be the same as the functional dependencies.

Type functions can be used to do all sorts of neat type-level computation, but perhaps the most basic use is to allow the construction of generic APIs, instead of just relying on the fact that a module exports “mostly the same functions”. How much type trickery you need depends on properties of your API—perhaps most importantly, on the properties of your data types.

Suppose I have a single function on a single data type:

defaultInt :: Int

and I would like to generalize it. I can do so easily by creating a type class:

class Default a where

def :: a

Abstraction on a single type usually requires nothing more than vanilla type classes.

Suppose I have a function on several data types:

data IntSet

insert :: IntSet -> Int -> IntSet

lookup :: IntSet -> Int -> Bool

We’d like to abstract over IntSet and Int. Since all of our functions mention both types, all we need to do is write a multiparameter type class:

class Set c e where

insert :: c -> e -> c

lookup :: c -> e -> Bool

instance Set IntSet Int where ...

If we’re unlucky, some of the functions will not use all of the data types:

empty :: IntSet

In which case, when we attempt to use the function, GHC will tell us it can’t figure out what instance to use:

No instance for (Set IntMap e)

arising from a use of `empty'

One thing to do is to introduce a functional dependency between IntSet and Int. A dependency means something is depending on something else, so which type depends on what? We don’t have much choice here: since we’d like to support the function empty, which doesn’t mention Int anywhere in its signature, the dependency will have to go from IntSet to Int, that is, given a set (IntSet), I can tell you what it contains (an Int).:

class Set c e | c -> e where

empty :: c

insert :: c -> e -> c

lookup :: c -> e -> Bool

Notice that this is still fundamentally a multiparameter type class, we’ve just given GHC a little hint on how to pick the right instance. We can also introduce a fundep in the other direction, if we need to allow a plain e. For pedagogical purposes, let’s assume that our boss really wants a “null” element, which is always a member of a Set and when inserted doesn’t do anything:

class Set c e | c -> e, e -> c where

empty :: c

null :: e

insert :: c -> e -> c

lookup :: c -> e -> Bool

Also notice that whenever we add a functional dependency, we preclude ourselves from offering an alternative instance. The following is illegal with the last typeclass for Set:

instance Set IntSet Int where ...

instance Set IntSet Int32 where ...

instance Set BetterIntSet Int where ...

This will report a “Functional dependencies conflict.”

Functional dependencies are somewhat maligned because they interact poorly with some other type features. An equivalent feature that was recently added to GHC is associated types (also known as type families or data families.)

Instead of telling GHC how automatically infer one type from the other (via the dependency), we create an explicit type family (also known as a type function) which provides the mapping:

class Set c where

data Elem c :: *

empty :: c

null :: Elem c

insert :: c -> Elem c -> c

lookup :: c -> Elem c -> Bool

Notice that our typeclass is no longer multiparameter: it’s a little like as if we introduced a functional dependency from c -> e. But then, how does it know what the type of null should be? Easy: it makes you tell it:

instance Set IntSet where

data Elem IntSet = IntContainer Int

empty = emptyIntSet

null = IntContainer 0

Notice on the right hand side of data is not a type: it’s a data constructor and then a type. The data constructor will let GHC know what instance of Elem to use.

In the original version of this article, I had defined the type class in the opposite direction:

class Key e where

data Set e :: *

empty :: Set e

null :: e

insert :: Set e -> e -> Set e

lookup :: Set e -> e -> Bool

Our type function goes the other direction, and we can vary the implementation of the container based on what type is being used, which may not be one that we own. This is one primary use case of data families, but it’s not directly related to the question of generalizing APIs, so we leave it for now.

IntContainer looks a lot like a newtype, and in fact can be made one:

instance Set IntSet where

newtype Elem IntSet = IntContainer Int

If you find wrapping and unwrapping newtypes annoying, in some circumstances you can just use a type synonym:

class Set c where

type Elem c :: *

instance Set IntSet where

type Elem IntSet = Int

However, this rules out some functions you might like to write, for example, automatically specializing your generic functions:

x :: Int

x = null

GHC will error:

Couldn't match expected type `Elem e'

against inferred type `[Int]'

NB: `Container' is a type function, and may not be injective

Since I could have also written:

instance Set BetterIntSet where

type Elem BetterIntSet = Int

GHC doesn’t know which instance of Set to use for null: IntSet or BetterIntSet? You will need for this information to be transmitted to the compiler in another way, and if this happens completely under the hood, you’re a bit out of luck. This is a distinct difference from functional dependencies, which conflict if you have a non-injective relation.

Another method, if you have the luxury of defining your data type, is to define the data type inside the instance:

instance Set RecordMap where

data Elem RecordMap = Record { field1 :: Int, field2 :: Bool }

However, notice that the type of the new Record is not Record; it’s Elem RecordMap. You might find a type synonym useful:

type Record = Elem RecordMap

There is not too much difference from the newtype method, except that we avoided adding an extra layer of wrapping and unwrapping.

In many cases, we would like to stipulate that a data type in our API has some type class:

instance Ord Int where ...

One low tech way to enforce this is add it to all of our function’s type signatures:

class Set c where

data Elem c :: *

empty :: c

null :: Ord (Elem c) => Elem c

insert :: Ord (Elem c) => c -> Elem c -> c

lookup :: Ord (Elem c) => c -> Elem c -> Bool

But an even better way is to just add a class constraint on Set with flexible contexts:

class Ord (Elem c) => Set c where

data Elem c :: *

empty :: c

null :: Elem c

insert :: c -> Elem c -> c

lookup :: c -> Elem c -> Bool

We can make functions and data types generic. Can we also make type classes generic? :

class ToBloomFilter a where

toBloomFilter :: a -> BloomFilter

Suppose that we decided that we want to allow multiple implementations of BloomFilter, but we would still like to give a unified API for converting things into whatever bloom filter you want.

Not directly, but we can fake it: just make a catch all generic type class and parametrize it on the parameters of the real type class:

class BloomFilter c where

data Elem c :: *

class BloomFilter c => ToBloomFilter c a where

toBloomFilter :: a -> c

Step back for a moment and compare the type signatures that functional dependencies and type families produce:

insertFunDeps :: Set c e => c -> e -> c

insertTypeFamilies :: Set c => c -> Elem c -> c

emptyFunDeps :: Set c e => c

emptyTypeFamilies :: Set c => c

So type families hide implementation details from the type signatures (you only use the associated types you need, as opposed to Set c e => c where the e is required but not used for anything—this is more obvious if you have twenty associated data types). However, they can be a bit more wordy when you need to introduce newtype wrappers for your associated data (Elem). Functional dependencies are great for automatically inferring other types without having to repeat yourself.

(Thanks Edward Kmett for pointing this out.)

What to do from here? We’ve only scratched the surface of type level programming, but for the purpose of generalizing APIs, this is essentially all you need to know! Find an API you’ve written that is duplicated across several modules, each of which provide different implementations. Figure out what functions and data types are the primitives. If you have many data types, apply the tricks described here to figure out how much type machinery you need. The go forth, and make thy API generic!

August 11, 2010Prologue. This post is an attempt to solidify some of the thoughts about the upcoming Hackage 2.0 that have been discussed around the Galois lunch table. Note that I have never overseen the emergence of a language into mainstream, so take what I say with a grain of salt. The thesis is that Hackage can revolutionize what it means to program in Haskell if it combines the cathedral (Python), the bazaar (Perl/CPAN), and the wheels of social collaboration (Wikipedia, StackOverflow, Github).

New programming languages are a dime a dozen: one only needs to stroll down the OSCON Emerging Languages track to see why. As programmers, our natural curiosity is directed towards the language itself: “What problems does it solve? What does it look like?” As engineers, we might ask “What is its runtime system?” As computer scientists, we might ask: “What novel research has been incorporated into this language?” When a language solves a problem we can relate to or shows off fancy new technology, our interest is whetted, and we look more closely.

But as the language grows and gains mindshare, as it moves beyond the “emerging” phase and into “emergent”, at some point, the language stops being important. Instead, it is the community around the language that takes over: both socially and technically. A community of people and a community of code—the libraries, frameworks, platforms. An engineer asks: “Ok. I need to do X. Is there a library that fills this need?”

The successful languages are the ones that can unambiguously answer, “Yes.” It’s a bit of an obvious statement, really, since the popular languages attract developers who write more libraries which attracts more developers: a positive feedback loop. It’s also not helpful for languages seeking to break into the mainstream.

Tune down the popularity level a little, and then you can see languages defined by the mechanism by which developers can get the functionality they need. Two immediate examples are Python and Perl.

Python has the mantra: “batteries included,” comparing a language without libraries to a fancy piece of technology that doesn’t have batteries: pretty but—at the moment—pretty useless. The Python documentation boasts about the fact that any piece of basic functionality is only an import away on a vanilla Python install. The Python standard library itself follows a cathedral model: commits are restricted to members of python-dev, a list of about 120 trusted people. Major additions to the standard library, including the addition of new modules most go through a rigorous proposal process in which they demonstrate that your module is accepted, widely used and will be actively maintained. If a maintainer disappears, python-dev takes stewardship of the module while a new maintainer is found, or deprecates the module if no one is willing to step up to maintain it. This model has lead to over three hundred relatively high-quality modules in the standard library.

On the other hand, Perl has adopted the bazaar model with CPAN, to the point where the slow release cycle of core Perl has meant that some core modules have been dual-lifed: that is, they exist in both the core and CPAN. Absolutely anyone can upload to CPAN: the result is over 20,000 modules and a resource many Perl developers consider indispensable. Beyond its spartan home interface, there is also massive testing infrastructure for all of CPAN and a ratings system (perhaps of dubious utility). CPAN has inspired similar bazaar style repositories across many programming languages (curiously enough, some of the most popular langauges—C and Java—have largely resisted this trend).

It’s a tall order for any language to build up over a hundred trusted committers or a thriving community on the scale of CPAN. But without this very mechanism, the language is dead out of the water. The average engineer would have to rewrite too much functionality for it to be useful as a general purpose language.

Which brings us back to the original point: where does Hackage stand?

The recent results from the State of the Haskell 2010 survey gives voice to the feeling that any Haskell programmer who has attempted to use Hackage has gotten. There are too many libraries without enough quality.

How do we fix this? After all, it is all open source made by volunteers: you can’t go around telling people to make their libraries better. Does one increase the set of core modules—that is, the Haskell platform—and the number of core contributors, requiring a rigorous quality review (the Python model)? Or do you let natural evolution take place and add mechanisms for measuring popularity (the Perl model)?

To succeed, I believe Hackage needs to do both. And if it succeeds, I believe that it may become the model for growing your standard library.

The cathedral model is the obvious solution to rapidly increase the quality of a small number of packages. Don Stewart has employed this to good effect before: bytestring started off as a hobby project, before the Haskell community realized how important efficiently packed strings were. A “strike team” of experienced Haskellers was assembled and the code was heavily improved, fleshed out and documented, generating several papers in the process. Now bytestring is an extremely well tuned library that is the basis for efficient input and output in Haskell. Don has suggested that we should adopt similar strike teams for the really important pieces of functionality. We can encourage this process by taking libraries that are deemed important into a shared repository that people not the primary maintainer can still help do basic maintenance and bugfixes.

But this process is not scalable. For one, growing a set of trusted maintainers is difficult. The current base libraries are maintained by a very small number of people: one has to wonder how much time the Simons spend maintaining base when they could be doing work on GHC. And you can only convince most people to take maintainership of X packages before they wise up. (Active maintainership of even a single package can be extremely time consuming.)

Hackage 2.0 is directed at facilitating the Bazaar model. Package popularity and reverse dependencies can help a developer figure out whether or not it is something worth using.

But if we consider both developers and package maintainers, we are tackling a complex socio-technical problem, for which we don’t have a good idea what will revolutionize the bazaar. Would a StackOverflow style reputation system encourage maintainers to polish their documentation? Would a Wikipedian culture of rewarding contributors with increased privileges help select the group of trusted stewards? Would the ability to fork any package instantly ala GitHub help us get over our obsession with official packages? Most of these ideas have not been attempted with a system so integral to the fabric of a programming language, and we have no way of telling if they will work or not without implementing them!

I am cautiously optimistic that we are at the cusp of a major transformation of what Hackage represents to the Haskell community. But to make this happen, we need your help. Vive la révolution!

Credit. Most of these ideas are not mine. I just wrote them down. Don Stewart, in particular, has been thinking a lot about this problem.

August 9, 2010Over the weekend, I took the Greyhound up to Seattle to meet up with some friends. The Greyhound buses was very late: forty-five minutes in the case of the trip up, which meant that I had some time to myself in the Internet-less bus station. I formulated the only obvious course of action: start working on the backlog of papers in my queue. In the process, I found out that a paper that had been languishing in my queue since December 2009 actually deals directly with a major problem I spent last Thursday debugging (unsuccessfully) at Galois.

Here are the papers and slide-decks I read—some old, some new—and why you might care enough to read them too. (Gosh, and they’re not all Haskell either!)

Popularity is Everything (2010) by Schechter, Herley and Mitzenmacher. Tagline: When false positives are a good thing!

We propose to strengthen user-selected passwords against statistical-guessing attacks by allowing users of Internet-scale systems to choose any password they want-so long as it’s not already too popular with other users. We create an oracle to identify undesirably popular passwords using an existing data structure known as a count-min sketch, which we populate with existing users’ passwords and update with each new user password. Unlike most applications of probabilistic data structures, which seek to achieve only a maximum acceptable rate false-positives, we set a minimum acceptable false-positive rate to confound attackers who might query the oracle or even obtain a copy of it.

Nelson informed me of this paper; it is a practical application of probabilistic data structures like Bloom filters that takes advantage of their false positive rate: attackers who try to use your password popularity database to figure out what passwords are popular will get a large number of passwords which are claimed to be popular but are not. The data structure is pretty easy too: someone should go integrate this with the authentication mechanism of a popular web framework as weekend project!

Ropes: an Alternative to Strings (1995) by Boehm, Atkinson and Plass. Tagline: All you need is concatenation.

Programming languages generally provide a ‘string’ or ‘text’ type to allow manipulation of sequences of characters. This type is usually of crucial importance, since it is normally mentioned in most interfaces between system components. We claim that the traditional implementations of strings, and often the supported functionality, are not well suited to such general-purpose use. They should be confined to applications with specific, and unusual, performance requirements. We present ‘ropes’ or ‘heavyweight’ strings as an alternative that, in our experience leads to systems that are more robust, both in functionality and in performance.

When is the last time you indexed into a string to get a single character? If you are dealing with a multibyte encoding, chances are this operation doesn’t even mean anything! Rather, you are more likely to care about searching or slicing or concatenating strings. Practitioners may dismiss this as a preoccupation with asymptotic and not real world performance, but the paper makes a very good point that text editors are a very practical illustration of traditional C strings being woefully inefficient. Ropes seem like a good match for web developers, who spend most of their time concatenating strings together.

Autotools tutorial (last updated 2010) by Duret-Lutz. (Rehosted since the canonical site seems down at time of writing.) Tagline: Hello World: Autotools edition.

This presentation targets developers familiar with Unix development tools (shell, make, compiler) that want to learn Autotools

Despite its unassuming title, this slide deck has become the default recommendation by most of my friends if you want to figure out what this “autogoo” thing is about. In my case, it was portably compiling shared libraries. Perhaps what makes this presentation so fantastic is that it assumes the correct background (that is, the background that most people interested but new to autotools would have) and clearly explains away the black magic with many animated diagrams of what programs generate what files.

Fun with Type Functions (2009) by Oleg Kiselyov, Simon Peyton Jones and Chung-chieh Shan. See also Haskellwiki. Tagline: Put down those GHC docs and come read this.

Haskell’s type system extends Hindley-Milner with two distinctive features: polymorphism over type constructors and overloading using type classes. These features have been integral to Haskell since its beginning, and they are widely used and appreciated. More recently, Haskell has been enriched with type families, or associated types, which allows functions on types to be expressed as straightforwardly as functions on values. This facility makes it easier for programmers to effectively extend the compiler by writing functional programs that execute during type-checking.

Many programmers I know have an aversion to papers and PDFs: one I know has stated that if he could, he’d pay people to make blog posts instead of write papers. Such an attitude would probably make them skip over a paper like this, which truly is the tutorial for type families that you’ve been looking for. There is no discussion of the underlying implementation: just thirty-five pages of examples of type level programming. Along the way they cover interfaces for mutable references (think STRef and IORef), arithmetic, graphs, memoization, session types, sprintf/scanf, pointer alignment and locks! In many ways, it’s the cookbook I mentioned I was looking for in my post Friday.

Purely Functional Lazy Non-deterministic Programming (2009) by Sebastian Fischer, Oleg Kiselyov and Chung-chieh Shan. Tagline: Sharing and caring can be fun!

Functional logic programming and probabilistic programming have demonstrated the broad benefits of combining laziness (non-strict evaluation with sharing of the results) with non-determinism. Yet these benefits are seldom enjoyed in functional programming, because the existing features for non-strictness, sharing, and non-determinism in functional languages are tricky to combine.

We present a practical way to write purely functional lazy non-deterministic programs that are efficient and perspicuous. We achieve this goal by embedding the programs into existing languages (such as Haskell, SML, and OCaml) with high-quality implementations, by making choices lazily and representing data with non-deterministic components, by working with custom monadic data types and search strategies, and by providing equational laws for the programmer to reason about their code.

This is the paper that hit right at home with of some code I’ve been wrangling with at work: I’ve essentially been converting a pure representation of a directed acyclic graph into a monadic one, and along the way I managed to break sharing of common nodes so that the resulting tree is exponential. The explicit treatment of sharing in the context of nondeterminism in order to get some desirable properties helped me clarify my thinking about how I broke sharing (I now fully agree with John Matthews in that I need an explicit memoization mechanism), so I’m looking forward to apply some of these techniques at work tomorrow.

That’s it for now, or at least, until the next Paper Monday! (If my readers don’t kill me for it first, that is. For the curious, the current backlog is sixty-six papers long, most of them skimmed and not fully understood.)

August 6, 2010David Powell asks,

There seems to be decent detailed information about each of these [type extensions], which can be overwhelming when you’re not sure where to start. I’d like to know how these extensions relate to each other; do they solve the same problems, or are they mutually exclusive?

Having only used a subset of GHC’s type extensions (many of them added only because the compiler told me to), I’m unfortunately terribly unqualified to answer this question. In the cases where I’ve gone out of my way to add a language extension, most of the time it’s been because I was following some specific recipe that called for that type. (Examples of the former include FlexibleInstances, MultiParamTypeClasses, and FlexibleContexts; examples of the latter include GADTs and EmptyDataDecl).

There is, however, one language extension that I have found myself increasingly relying on and experimenting with—you could call it my gateway drug to type level programming. This extension is Rank2Types. (Tim Carstens appears to be equally gaga at this feature.)

The reason why this feature speaks so powerfully to me is that it lets me encode an invariant that I see all the time in imperative code: when a resource is released, you should not use it anymore. Whether for memory, files or network connections, the resource handle is ubiquitous. But normally, you can only write:

FILE *fh = fopen("foobar.txt", "r");

fread(buf, sizeof(char), 100, fh);

fclose(fh);

// ...

fread(buf, sizeof(char), 2, fh); // oops

so you rely on the file handle being available in a small enough scope so that it’s obvious if you’re using it incorrectly, or if the handle is to be available in a global context, you add runtime checks that it’s hasn’t been closed already and hope that no one’s messed it up a thousand lines of code away.

So the moment I realized that I could actually enforce this statically, I was thrilled. What other invariants can I move from runtime to compile time? Luckily, the system I was working on offered more opportunities for type-level invariant enforcement, stepping from “released resources cannot be reused” to “components bound to one resource should not be mixed with another resource” and “exception to previous rule: components can be used for another resource, but only if the target resource came from the source resource, and you need to call a translation function.” These are fairly complicated invariants, and I was quite pleased when I found that I was able to encode these in the type system. In fact, this was a turning point: I’d moved beyond cookbook types to type programming.

So, how do you discover your gateway drug to type programming? I feel that right now, there are two ways:

- Consider all type system features and extensions to be intrinsically useful, study each of them to learn their capabilities and obvious use-cases, and hope that at some point you know the primitives well enough to start fitting them together. (As for many other things, I feel that knowing the fundamentals is the only way to get to truly understand a system, but I personally find this approach very daunting.)

- Get acquainted with the canonical use-cases for any given type system feature and extension, accumulating a cookbook-like repository of type system possibilities. Stumble upon a real problem that is precisely the use-case, implement it, and then start tinkering at the edges to extend what you can do. (This is how I got hooked, but it has also left me at a loss as to a methodology—a common framework of thought as opposed to isolated instances of cleverness.)

In fact, this seems quite similar to the learning process for any programming language. There are several types of learning materials that I would love to know about:

- A comprehensive cookbook of type level encodings of invariants that are normally checked at runtime. It would show the low-tech, runtime-verified program, and then show the abstractions and transformations necessary to move the invariant to types. It would collect all of the proposed use-cases that all of the various literature has explored for various type extensions under a uniform skin, a kind of Patterns book. A catalog of Oleg’s work would be a good place to start.

- When I reuse a type variable in an expression such as

Foo a -> Foo a, I’ve state that whatever type the left side is, the right side must be the same too. You might usually associate a with a usual type like Int or Char, and Foo as some sort of container. But we can put stranger types in this slot. If Foo uses a as a phantom type, I can use empty types to distinguish among a fixed set of types without any obligation to supply a corresponding value to Foo. If I use Rank2Types to make a bound to another universally quantified type forall b. b, I’ve a unique label which can be passed along but can’t be forged. What is actually going on here? What does the “types as propositions” (Curry-Howard) viewpoint say about this? - What kinds of type programming result in manageable error messages, and what types of type programming result in infamous error messages? When I first embarked on my API design advantage, a fellow engineer at Galois warned me, “If you have to sacrifice some static analysis for a simpler type system, do it. Things like type level numbers are not worth it.” I may have wandered too far off into the bushes already!

I’m sure that some of this literature exists already, and would love to see it. Bring on the types!

August 5, 2010Bonus post today! Last Tuesday, John Erickson gave a Galois tech talk entitled “Industrial Strength Distributed Explicit Model Checking” (video), in which he describe PReach, an open-source model checker based on Murphi that Intel uses to look for bugs in its models. It is intended as a simpler alternative to Murphi’s built-in distributed capabilities, leveraging Erlang to achieve much simpler network communication code.

First question. Why do you care?

- Model checking is cool. Imagine you have a complicated set of interacting parallel processes that evolve nondeterministically over time, using some protocol to communicate with each other. You think the code is correct, but just to be sure, you add some assertions that check for invariants: perhaps some configurations of states should never be seen, perhaps you want to ensure that your protocol never deadlocks. One way to test this is to run it in the field for a while and report when the invariants fail. Model checking lets you comprehensively test all of the possible state evolutions of the system for deadlocks or violated invariants. With this, you can find subtle bugs and you can find out precisely the inputs that lead to that event.

- Distributed applications are cool. As you might imagine, the number of states that need to be checked explodes exponentially. Model checkers apply algorithms to coalesce common states and reduce the state space, but at some point, if you want to test larger models you will need more machines. PReach has allowed Intel to run the underlying model checker Murphi fifty times faster (with a hundred machines).

This talk was oriented more towards to the challenges that the PReach team encountered when making the core Murphi algorithm distributed than how to model check your application (although I’m sure some Galwegians would have been interested in that aspect too.) I think it gave an excellent high level overview of how you might design a distributed system in Erlang. Since the software is open source, I’ll link to relevant source code lines as we step through the high level implementation of this system.

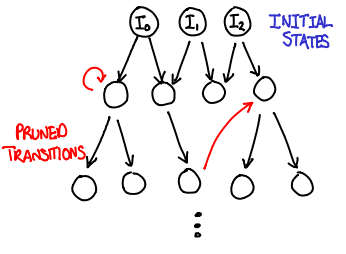

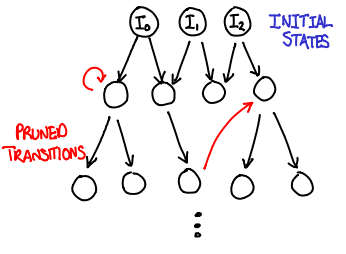

The algorithm. At its heart, model checking is simply a breadth-first search. You take the initial states, compute their successor states, and add those states to the queue of states to be processed. :

WQ : list of state // work queue

V : set of state // visited states

WQ := initial_states()

while !empty(WQ) {

s = dequeue(WQ)

foreach s' in successors(s) {

if !member(s', V) {

check_invariants(s')

enqueue(s', WQ)

add_element(s', V)

}

}

}

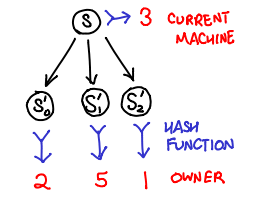

The parallel algorithm. We now need to make this search algorithm parallel. We can duplicate the work queues across computers, making the parallelization a matter of distributing the work load across a number of computers. However, the set of visited states is trickier: if we don’t have a way of partitioning it across machines, it becomes shared state and a bottleneck for the entire process.

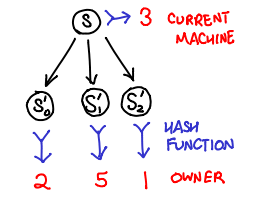

Stern and Dill (PS) came up with a clever workaround: use a hash function to distribute states to processors. This has several important implications:

- If the hash function is uniform, we now can distribute work evenly across the machines by splitting up the output space of the function.

- Because the hash function is deterministic, any state will always be sent to the same machine.

- Because states are sticky to machines, each machine can maintain an independent visited states and trust that if a state shows up twice, it will get sent to the same machine and thus show up in the visited states of that machine.

One downside is that a machine cannot save network latency by deciding to process it’s own successor states locally, but this is a fair tradeoff for not having to worry about sharing the visited states, which is considered a hard problem to do efficiently.

The relevant source functions that implement the bulk of this logic are recvStates and reach.

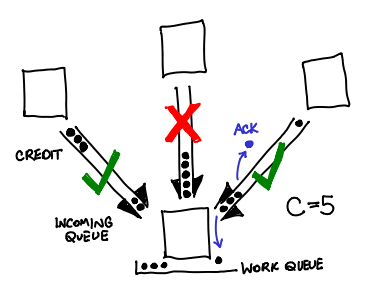

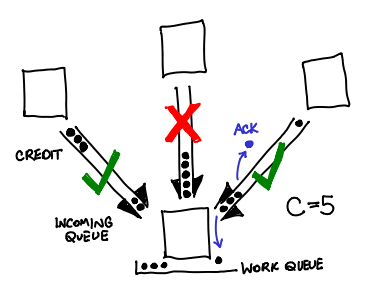

Crediting. When running early versions of PReach, the PReach developers would notice that occasionally a machine in the cluster would massively slow down or crash nondeterministically.

It was discovered that this machine was getting swamped by incoming states languishing in the in-memory Erlang request queue: even though the hash function was distributing the messages fairly evenly, if a machine was slightly slower than its friends, it would receive states faster than it could clear out.

To fix this, PReach first implemented a back-off protocol, and then implemented a crediting protocol. The intuition? Don’t send messages to a machine if it hasn’t acknowledged your previous C messages. Every time a message is sent to another machine, a credit is sent along with it; when the machine replies back that it has processed the state, the credit is sent back. If there are no credits, you don’t send any messages. This bounds the number of messages in the queue to be N * C, where N is the number of nodes (usually about a 100 when Intel runs this). To prevent a build-up of pending states in memory when we have no more credits, we save them to disk.

Erickson was uncertain if Erlang had a built-in that performed this functionality; to him it seemed like a fairly fundamental extension for network protocols.

Load balancing. While the distribution of states is uniform, once again, due to a heterogeneous environment, some machines may be able to process states faster than other. If those machines finish all of their states, they may sit idly by, twiddling their thumbs, while the slower machines still work on their queue.

One thing to do when this happens is for the busy nodes to notice that a machine is idling, and send them their states. Erickson referenced some work by Kumar and Mercer (PDF) on the subject. The insight was that overzealous load balancing was just as bad as no load balancing at all: if the balancer attempts to keep all queues exactly the same, it will waste a lot of network time pushing states across the network as the speeds of the machines fluctuate. Instead, only send states when you notice someone with X times less states than you (where X is around 5.)

One question that might come up is this: does moving the states around in this fashion cause our earlier cleverness with visited state checking to stop working? The answer is fortunately no! States on a machine can be in one of two places: the in-memory Erlang receive queue, or the on-disk work queue. When transferring a message from the receive to the work queue, the visited test is performed. When we push states to a slacker, those states are taken from our work queue: the idler just does the invariant checking and state expansion (and also harmlessly happens to add that state to their visited states list).

Recovering shared states. When an invariant fails, how do you create a backtrace that demonstrates the sequence of events that lead to this state? The processing of any given state is scattered across many machines, which need to get stitched together again. The trick is to transfer not only the current state when passing off successors, but also the previous state. The recipient then logs both states to disk. When you want to trace back, you can always look at the previous state and hash it to determine which machine that state came from.

In the field. Intel has used PReach on clusters of up to 256 nodes to test real models of microarchitecture protocols of up to thirty billion states (to Erickson’s knowledge, this is the largest amount of states that any model checker has done on real models.)

Erlang pain. Erickson’s primary complaint with Erlang was that it did not have good profiling facilities for code that interfaced heavily with C++; they would have liked to have performance optimized their code more but found it difficult to pin down where the slowest portions were. Perhaps some Erlang enthusiasts have some comments here?

August 4, 2010While attempting to figure out how I might explain lazy versus strict bytestrings in more depth without boring half of my readership to death, I stumbled upon a nice parallel between a standard implementation of buffered streams in imperative languages and iteratees in functional languages.

No self-respecting input/output mechanism would find itself without buffering. Buffering improves efficiency by grouping reads or writes together so that they can be performed as a single unit. A simple read buffer might be implemented like this in C (though, of course, with the static variables wrapped up into a data structure… and proper handling for error conditions in read…):

static char buffer[512];

static int pos = 0;

static int end = 0;

static int fd = 0;

int readChar() {

if (pos >= end && feedBuf() == 0) {

return EOF;

}

return (int) buffer[pos++];

}

int feedBuf() {

pos = 0;

end = read(fd, buffer, sizeof(buffer));

assert(end != -1);

return end;

}

The exported interface is readChar, which doles out a single char cast to an int every time a user calls it, but behind the scenes only actually reads from the input if it has run out of buffer to supply (pos >= end).

For most applications, this is good enough: the chunky underlying behavior is hidden away by a nice and simple function. Furthermore, our function is not too simple: if we were to read all of standard input into one giant buffer, we wouldn’t be able to do anything else until the EOF comes along. Here, we can react as the input comes in.

What would such a set of functions look like in a purely functional setting? One obvious difficulty is the fact that buffer is repeatedly mutated as we perform reads. In the spirit of persistence, we should very much prefer that our buffer not be mutated beyond when we initially fill it up. Making the buffer persistent means we also save ourselves from having to copy the data out if we want to hold onto it while reading in more data (you could call this zero copy). We can link buffers together using something simple: say, a linked list.

Linked lists eh? Let’s pull up the definition for lazy and strict ByteStrings (slightly edited for you, the reader):

data Strict.ByteString = PS !(ForeignPtr Word8) !Int !Int

data Lazy.ByteString = Empty | Chunk !Strict.ByteString Lazy.ByteString

In C, these would be:

struct strict_bytestring {

char *pChar;

int offset;

int length;

}

struct lazy_bytestring {

struct strict_bytestring *cur;

int forced;

union {

struct lazy_bytestring *next;

void (*thunk)(struct lazy_bytestring*);

}

}

The Strict.ByteString is little more than a glorified, memory-managed buffer: the two integers track offset and length. Offset is an especially good choice in the presence of persistence: taking a substring of a string no longer requires a copy: just create a new strict ByteString with the offset and length set appropriately, and use the same base pointer.

So what is Lazy.ByteString? Well, it’s a glorified lazy linked list of strict ByteStrings—just read Chunk as Cons, and Empty as Null: the laziness derives from the lack of strictness on the second argument of Chunk (notice the lack of an exclamation mark, which is a strictness annotation). The laziness is why we have the thunk union and forced boolean in our lazy_bytestring struct: this API scribbles over the function pointer with the new lazy_bytestring when it is invoked. (This is not too different from how GHC does it; minus a layer of indirection or so.) If we ignore the laziness, this sounds a bit like the linked list of buffers we described earlier.

There is an important difference, however. A Lazy.ByteString is pure: we can’t call the original read function (a syscall, which makes it about as IO as you can get). So lazy ByteStrings are appropriate for when we have some pure computation (say, a Markov process) which can generate infinite amounts of text, but are lacking when it comes to buffering input.

“No problem!” you might say, “Just change the datatype to hold an IO Lazy.ByteString instead of a Lazy.ByteString:

data IO.ByteString = Empty | Chunk !Strict.ByteString (IO IO.ByteString)

But there’s something wrong about this datatype: nothing is stopping someone from invoking IO IO.ByteString multiple times. In fact, there’s no point in placing the IO operation in the Chunk value: due to the statefulness of file descriptors, the IO operation is the same code every time: hReadByteString handle. We’re back to handle-based IO.

The idea of IO.ByteString as a list is an important intuition, however. The key insight is this: who said that we have to give the list of IO actions to the user? Instead, invert the control so that the user doesn’t call the iteratee: the iteratee calls the user with the result of the IO. The user, in turn, can initiate other IO, or compose iteratees together (something we have not discussed) to stream from one iteratee to another.

At this point, I defer to Oleg’s excellent annotated slides (PDF) for further explanation of iteratees (no really, the slides are extremely well written), as well as the multitude of iteratee tutorials. My hope is that the emphasis on the “linked list of buffers” generated by IO operations directs some attention towards the fundamental nature of an iteratee: an abstraction on top of a list of IO actions.

To summarize:

- Use strict bytestrings as a primitive for building more interesting structures that have buffers (though avoid reimplementing lazy bytestrings or iteratees). Use them when the amount of data is small, when all of it can be initialized at once, or when random access, slicing and other non-linear access patterns are important.

- Use lazy bytestrings as a mechanism for representing infinite streams of data generated by pure computation. Consider using them when performing primarily operations well suited for lazy lists (

concat, append, reverse etc). Avoid using them for lazy IO (despite what the module says on the tin). - Use iteratees for representing data from an IO source that can be incrementally processed: this usually means large datasets. Iteratees are especially well suited for multiple layers of incremental processing: they “fuse” automatically and safely.