November 5, 2010Someone told me it’s all happening at the zoo…

I’ve always thought dynamic programming was a pretty crummy name for the practice of storing sub-calculations to be used later. Why not call it table-filling algorithms, because indeed, thinking of a dynamic programming algorithm as one that fills in a table is a quite good way of thinking about it.

In fact, you can almost completely characterize a dynamic programming algorithm by the shape of its table and how the data flows from one cell to another. And if you know what this looks like, you can often just read off the complexity without knowing anything about the problem.

So what I did was collected up a bunch of dynamic programming problems from Introduction to Algorithms and drew up the tables and data flows. Here’s an easy one to start off with, which solves the Assembly-Line problem:

The blue indicates the cells we can fill in ‘for free’, since they have no dependencies on other cells. The red indicates cells that we want to figure out, in order to pick the optimal solution from them. And the grey indicates a representative cell along the way, and its data dependency. In this case, the optimal path for a machine to a given cell only depends on the optimal paths to the two cells before it. (Because, if there was a more optimal route, than it would have shown in my previous two cells!) We also see there are a constant number of arrows out of any cell and O(n) cells in this table, so the algorithm clearly takes O(n) time total.

Here’s the next introduction example, optimal parenthesization of matrix multiplication.

Each cell contains the optimal parenthesization of the subset i to j of matrixes. To figure this out the value for a cell, we have to consider all of the possible combos of existing parentheticals that could have lead to this (thus the multiple arrows). There are O(n²) boxes, and O(n) arrows, for O(n³) overall.

Here’s a nice boxy one for finding the longest shared subsequence of two strings. Each cell represents the longest shared subsequence of the first string up to x and the second string up to y. I’ll let the reader count the cells and arrows and verify the complexity is correct.

There aren’t that many ways to setup dynamic programming tables! Constructing optimal binary search trees acts a lot like optimal matrix parenthesization. But the indexes are a bit fiddly. (Oh, by the way, Introduction to Algorithms is 1-indexed; I’ve switched to 0-indexing here for my examples.)

Here we get into exercise land! The bitonic Euclidean traveling salesman problem is pretty well-known on the web, and its tricky recurrence relation has to do with the bottom edge. Each cell represents the optimal open bitonic route between i and j.

The lovely word wrapping problem, a variant of which lies at the heart of the Knuth TeX word wrapping algorithm, takes advantage of some extra information to bound the number of cells one has to look back. (The TeX algorithm does a global optimization, so the complexity would be O(n²) instead.) Each cell represents the optimal word wrapping of all the words up to that point.

Finally, the edit problem, which seems like the authors decided to pile on as much complexity as they could muster, falls out nicely when you realize each string operation they order you to design corresponds to a single arrow to some earlier cell. Useful! Each cell is the optimal edit chain from that prefix of the source to that prefix of the destination.

And the zookeeper is very fond of rum.

Squares, triangles, rectangles, those were the tables I usually found. I’m curious to know if there are more exotic tables that DP algorithms have filled out. Send them in and I’ll draw them!

November 3, 2010Should software engineers be required to implement the abstractions use before using them? (Much like how before you’re allowed to use a theorem in a math textbook, you have to prove it first.) A bit like reinventing the wheel for pedagogical purposes.

(I’ve been sick since Saturday, so it’s a Dead Edward Day. Hopefully I’ll clean up the DP Zoo post and present it with more annotations for this Friday.)

November 1, 2010

October 29, 2010My parents like foisting various self-help books on me, and while I sometimes groan to myself about it, I do read (or at least skim) them and extract useful bits of information out of them. This particular title quote is from Robert Kiyosaki’s “rich dad” in Rich Dad, Poor Dad.

“Intelligence is the ability to make finer distinctions” really spoke to me. I’ve since found it to be an extremely effective litmus test to determine if I’ve really understood something. A recent example comes from my concurrent systems class, where there are many extremely similar methods of mutual exclusion: mutexes, semaphores, critical regions, monitors, synchronized region, active objects, etc. True knowledge entails an understanding of the conceptual details differentiating these gadgets. What are the semantics of a signal on a condition variable with no waiting threads? Monitors and synchronized regions will silently ignore the signal, thus requiring an atomic release-and-wait, whereas a semaphore will pass it on to the next wait. Subtle.

We can frequently get away with a little sloppiness of thinking, indeed, this is the mark of an expert: they know precisely how much sloppiness they can get away with. However, from a learning perspective, we’d like to be able to make as fine a distinction as possible, and hopefully derive some benefit (either in the form of deeper understanding or a new tool) from it.

Since this is, after all, an advocacy piece, how does learning Haskell help you make finer distinctions in software? You don’t have to look hard:

Haskell is a standardized, general-purpose purely functional programming language, with non-strict semantics and strong static typing.

These two bolded terms are concepts that Haskell asks you to make a finer distinction on.

Purity. Haskell requires you to make the distinction between pure code and input-output code. The very first time you get the error message “Couldn’t match expected type [a] against inferred type IO String” you are well on your way to learning this distinction. Fundamentally, it is the difference between computation and interaction with the outside world, and no matter how imperative your task is, both of these elements will be present in a program, frequently lumped together with no indication which is which.

Pure code confers tremendous benefits. It is automatically thread safe and asynchronous exception safe. It has no hidden dependencies with the outside world. It is testable and deterministic. The system can speculatively evaluate pure code with no commitment to the outside world, and can cache the results without fear. Haskellers have an obsession with getting as much code outside of IO as possible: you don’t have to go to such lengths, but even in small doses Haskell will make you appreciate how what is considered good engineering practice can be made rigorous.

Non-strict semantics. There are some things you take for granted, the little constants in life that you couldn’t possibly imagine be different. Perhaps if you stopped and thought about it, there was another way, but the possibility never occurred to you. Which side of the road you drive is one of these things; strict evaluation is another. Haskell asks you to distinguish between strict evaluation and lazy evaluation.

Haskell isn’t as in your face about this distinction as it is about purity and static typing, so it’s possible to happily hack along without understanding this distinction until you get your first stack overflow. At which point, if you don’t understand this distinction, the error will seem impenetrable (“but it worked in the other languages I know”), but if you are aware, a stack overflow is easily fixed—perhaps making the odd argument or data constructor explicitly strict.

Implicit laziness has a number of notable benefits. It permits user-level control structures. It encodes streams and other infinite data structures. It is more general* than strict evaluation. It is critical in the construction of amortized persistent data structures. (Okasaki) It also is not always appropriate to use: Haskell fosters an appreciation of the strengths and weaknesses of strictness and laziness.

* Well, almost. It only fully generalizes strict evaluation if you have infinite memory, in which case any expression that strictly evaluates also lazy evaluates, while the converse is not true. But in practice, we have such pesky things as finite stack size.

The downside. Your ability to make finer distinctions indicates your intelligence. But on the same token, if these distinctions don’t become second nature, they impose a cognitive overhead whenever you need invoke them. Furthermore, it makes it difficult for others who don’t understand the difference to effectively hack on your code. (Keep it simple!)

Managing purity is second-nature to experienced Haskellers: they’ve been drilled by the typechecker long enough to know what’s admissible and what’s not, and given the mystique of monads, it’s usually something people actively try to learn when starting off with Haskell. Managing strictness also comes easily to experienced Haskellers, but has what I perceive to be a higher learning curve: there is no strictness analyzer yelling at you when you make a suboptimal choice, and you can get away with not thinking about it most of the time. Some might say that lazy-by-default is not the right way to go, and are exploring the strict design space. I remain optimistic that we Haskellers can build up a body of knowledge and teaching techniques to induct novices into the mysteries and wonders of non-strict evaluation.

So there they are: purity and non-strictness, two distinctions that Haskell expects you to make. Even if you never plan on using Haskell for a serious project, getting a visceral feel for these two concepts will tremendously inform your other programming practice. Purity will inform you when you write thread-safe code, manage side-effects, handle interrupts, etc. Laziness will inform you when use generators, process streams, control structures, memoization, fancy tricks with function pointers, etc. These are seriously powerful engineering tools, and you owe it to yourself to check them out.

October 27, 2010…because I don’t live in a room numbered 245s anymore. Yep. :-)

This is a cow. They munch grass next to the River Cam.

Pop quiz. What do matrix-chain multiplication, longest common subsequence, construction of optimal binary search trees, bitonic euclidean traveling-salesman, edit distance and the Viterbi algorithm have in common?

October 25, 2010I’ve started formally learning OCaml (I’ve been reading ML since Okasaki, but I’ve never written any of it), and here are some notes about differences from Haskell from Jason Hickey’s Introduction to Objective Caml. The two most notable differences are that OCaml is impure and strict.

Features. Here are some features OCaml has that Haskell does not:

- OCaml has named parameters (

~x:i binds to i the value of named parameter x, ~x is a shorthand for ~x:x). - OCaml has optional parameters (

?(x:i = default) binds i to an optional named parameter x with default default). - OCaml has open union types (

[> 'Integer of int | 'Real of float] where the type holds the implementation; you can assign it to a type with type 'a number = [> 'Integer of int | 'Real of float] as a). Anonymous closed unions are also allowed ([< 'Integer of int | 'Real of float]). - OCaml has mutable records (preface record field in definition with

mutable, and then use the <- operator to assign values). - OCaml has a module system (only briefly mentioned today).

- OCaml has native objects (not covered in this post).

Syntax. Omission means the relevant language feature works the same way (for example, let f x y = x + y is the same)

Organization:

{- Haskell -}

(* OCaml *)

Types:

() Int Float Char String Bool (capitalized)

unit int float char string bool (lower case)

Operators:

== /= .&. .|. xor shiftL shiftR complement

= == != land lor lxor [la]sl [la]sr lnot

(arithmetic versus logical shift in Haskell depends on the type of the Bits.)

Float operators in OCaml: affix period (i.e. +.)

Float casting:

floor fromIntegral

int_of_float float_of_int

String operators:

++ !!i

^ .[i] (note, string != char list)

Composite types:

(Int, Int) [Bool]

int * int bool list

Lists:

x : [1, 2, 3]

x :: [1; 2; 3]

Data types:

data Tree a = Node a (Tree a) (Tree a) | Leaf

type 'a tree = Node of 'a * 'a tree * 'a tree | Leaf;;

(note that in OCaml you’d need Node (v,l,r) to match, despite there not actually being a tuple)

Records:

data MyRecord = MyRecord { x :: Int, y :: Int }

type myrecord = { x : int; y : int };;

Field access:

x r

r.x

Functional update:

r { x = 2 }

{ r with x = 2 }

(OCaml records also have destructive update.)

Maybe:

data Maybe a = Just a | Nothing

type 'a option = None | Some of 'a;;

Array:

readArray a i writeArray a i v

[|1; 3|] a.(i) a.(i) <- v

References:

newIORef writeIORef readIORef

ref := !

Top level definition:

x = 1

let x = 1;;

Lambda:

\x y -> f y x

fun x y -> f y x

Recursion:

let f x = if x == 0 then 1 else x * f (x-1)

let rec f x = if x == 0 then 1 else x * f (x-1)

Mutual recursion (note that Haskell let is always recursive):

let f x = g x

g x = f x

let rec f x = g x

and g x = f x

Function pattern matching:

let f 0 = 1

f 1 = 2

let f = function

| 0 -> 1

| 1 -> 2

(note: you can put pattern matches in the arguments for OCaml, but lack of an equational function definition style makes this not useful)

Case:

case f x of

0 -> 1

y | y > 5 -> 2

y | y == 1 || y == 2 -> y

_ -> -1

match f x with

| 0 -> 1

| y when y > 5 -> 2

| (1 | 2) as y -> y

| _ -> -1

Exceptions:

Definition

data MyException = MyException String

exception MyException of string;;

Throw exception

throw (MyException "error")

raise (MyException "error")

Catch exception

catch expr $ \e -> case e of

x -> result

try expr with

| x -> result

Assertion

assert (f == 1) expr

assert (f == 1); expr

Undefined/Error:

error "NYI"

failwith "NYI"

Build:

ghc --make file.hs

ocamlopt -o file file.ml

Run:

runghc file.hs

ocaml file.ml

Type signatures. Haskell supports specifying a type signature for an expression using the double colon. OCaml has two ways of specifying types, they can be done inline:

let intEq (x : int) (y : int) : bool = ...

or they can be placed in an interface file (extension mli):

val intEq : int -> int -> bool

The latter method is preferred, and is analogous to an hs-boot file as supported by GHC.

Eta expansion. Polymorphic types in the form of '_a can be thought to behave like Haskell’s monomorphism restriction: they can only be instantiated to one concrete type. However, in Haskell the monomorphism restriction was intended to avoid extra recomputation for values that a user didn’t expect; in OCaml the value restriction is required to preserve the soundness of the type system in the face of side effects, and applies to functions too (just look for the tell-tale '_a in a signature). More fundamentally, 'a indicates a generalized type, while '_a indicates a concrete type which, at this point, is unknown—in Haskell, all type variables are implicitly universally quantified, so the former is always the case (except when the monomorphism restriction kicks in, and even then no type variables are ever shown to you. But OCaml requires monomorphic type variables to not escape from compilation units, so there is a bit of similarity. Did this make no sense? Don’t panic.)

In Haskell, we’d make our monomorphic value polymorphic again by specifying an explicit type signature. In OCaml, we generalize the type by eta expanding. The canonical example is the id function, which when applied to itself (id id) results in a function of type '_a -> '_a (that is, restricted.) We can recover 'a -> 'a by writing fun x -> id id x.

There is one more subtlety to deal with OCaml’s impurity and strictness: eta expansion acts like a thunk, so if the expression you eta expand has side effects, they will be delayed. You can of course write fun () -> expr to simulate a classic thunk.

Tail recursion. In Haskell, you do not have to worry about tail recursion when the computation is lazy; instead you work on putting the computation in a data structure so that the user doesn’t force more of it than they need (guarded recursion), and “stack frames” are happily discarded as you pattern match deeper into the structure. However, if you are implementing something like foldl', which is strict, you’d want to pay attention to this (and not build up a really big thunk.)

Well, OCaml is strict by default, so you always should pay attention to making sure you have tail calls. One interesting place this comes up is in the implementation of map, the naive version of which cannot be tail-call optimized. In Haskell, this is not a problem because our map is lazy and the recursion is hidden away in our cons constructor; in OCaml, there is a trade off between copying the entire list to get TCO, or not copying and potentially exhausting stack space when you get big lists. (Note that a strict map function in Haskell would have the same problem; this is a difference between laziness and strictness, and not Haskell and OCaml.)

File organization. A single file OCaml script contains a list of statements which are executed in order. (There is no main function).

The moral equivalent of Haskell modules are called compilation units in OCaml, with the naming convention of foo.ml (lower case!) corresponding to the Foo module, or Foo.foo referring to the foo function in Foo.

It is considered good practice to write interface files, mli, as described above; these are like export lists. The interface file will also contain data definitions (with the constructors omitted to implement hiding).

By default all modules are automatically “imported” like import qualified Foo (no import list necessary). Traditional import Foo style imports (so that you can use names unqualified) can be done with open Foo in OCaml.

Module system. OCaml does not have type classes but it does have modules and you can achieve fairly similar effects with them. (Another classic way of getting type class style effects is to use objects, but I’m not covering them today.) I was going to talk about this today but this post is getting long so maybe I’ll save it for another day.

Open question. I’m not sure how much of this is OCaml specific, and how much generalizes to all ML languages.

Update. ocamlrun is not the same as runghc; I’ve updated the article accordingly.

Update 2. Raphael Poss has written a nice article in reverse: Haskell for OCaml programmers

October 22, 2010I am a member of a group called the Assassins’ Guild. No, we don’t kill people, and no, we don’t play the game Assassin. Instead, we write and run competitive live action role-playing games: you get some game rules describing the universe, a character sheet with goals, abilities and limitations, and we set you loose for anywhere from four hours to ten days. In this context, I’d like to describe a situation where applying the rule Don’t Repeat Yourself can be harmful.

The principle of Don’t Repeat Yourself comes up in a very interesting way when game writers construct game rules. The game rules are rather complex: we’d like players to be able to do things like perform melee attacks, stab each other in the back, conjure magic, break down doors, and we have to do this all without actually injuring anyone or harming any property, so, in a fashion typical of MIT students, we have “mechanics” for performing these in-game actions (for example, in one set of rules, a melee attack can be declared with “Wound 5”, where 5 is your combat rating, and if another individual has a CR of 5 or greater, they can declare “Resist”; otherwise, they have to role-play falling down unconscious and bleeding. It’s great fun.) Because there are so many rules necessary to construct a reasonable base universe, there is a vanilla, nine-page rules sheet that most gamewriters adapt for their games.

Of course, the rules aren’t always the same. One set of GMs (the people who write and run the game) may decide that a single CR rating is not enough, and that people should have separate attack and defense ratings. Another set of GMs might introduce robotic characters, who cannot die from bleeding out. And so forth.

So when we give rules out to players, we have two possibilities: we can repeat ourselves, and simply give them the full, amended set of rules. Or we can avoid repeating ourselves, and give out the standard rules and a list of errata—the specific changes made in our universe. We tend to repeat ourselves, since it’s easier to do with our game production tools. But an obvious question to ask is, which approach is better?

The answer is, of course, it depends.

- Veteran players who are well acquainted with the standard set of rules don’t need the entire set of rules given to them every time they play a game; instead, it would be much easier and more efficient for them if they were just given the errata sheet, so they can go, “Oh, hm, that’s different, ok” and go and concoct strategies for this altered game universe. This is particularly important for ten-days, where altered universe rules can greatly influence plotting and strategy.

- For new players who have never played a game before, being given a set of rules and then being told, “Oh, but disregard that and that and here is an extra condition for that case” would be very confusing! The full rules, repeated for the first few times they play a game, is helpful.

I think this same principle applies to Don’t Repeat Yourself as applied in software development. It’s good and useful to adopt a compact, unique representation for any particular piece of code or data, but don’t forget that a little bit of redundancy will greatly help out people learning your system for the first time! And to get the best of both worlds, you shouldn’t even have to repeat yourself: you should make the computer do it for you.

Postscript. For the curious, here is a PDF of the game rules we used for a game I wrote in conjunction with Alex Gurany and Jonathan Chapman, The Murder of Jefferson Douglass (working name A Dangerous Game).

Postscript II. When has repeating yourself been considered good design?

- Perl wants programmers to have to say as little as possible to get the job done, and this has given it a reputation as a “write only language.”

- Not all code that looks the same should be refactored into a function; there should be some logical unity to what is factored out.

- Java involves writing copious amounts of code: IDEs generate code for

hashCode and equals, and you possibly tweak it after the fact. Those who like Java controversially claim that this prevents Java programmers from doing too much damage (though some might disagree.) - When you write essays, even if you’ve already defined a term fifty pages ago, it’s good to refresh a reader’s memory. This is especially true for math textbooks.

- Haskell challenges you to abstract as much mathematically sound structure as possible. As a result, it makes people’s heads hurt, leads to combinator zoos up to the wazoo. But it’s also quite beneficial for even moderately advanced users.

Readers are encouraged to come up with more examples.

October 20, 2010In which the author muses that “semi-formal methods” (that is, non computer-assisted proof writing) should take a more active role in allowing software engineers to communicate with one another.

C++0x has a lot of new, whiz-bang features in it, one of which is the atomic operations library. This library has advanced features that enable compiler writers and concurrency library authors to take advantage of a relaxed memory model, resulting in blazingly fast concurrent code.

It’s also ridiculously bitchy to get right.

The Mathematizing C++ Concurrency project at Cambridge is an example of what happens when you throw formal methods at an exceedingly tricky specification: you find bugs. Lots of them, ranging from slight clarifications to substantive changes. As of a talk Mark Batty gave on Monday there are still open problems: for example, the sequential memory model isn’t actually sequential in all cases. You can consult the Pre-Rapperswil paper §4 for more details.

Which brings me to a piercing question:

When software engineers want to convince one another that their software is correct, what do they do?

This particular question is not about proving software “correct”—skeptics rightly point out that in many cases the concept of “correctness” is ill-defined. Instead, I am asking about communication, along the lines of “I have just written an exceptionally tricky piece of code, and I would now like to convince my coworker that I did it properly.” How do we do this?

We don’t.

Certainly there are times when the expense of explaining some particular piece of code is not useful. Maybe the vast majority of code we write is like this. And certainly we have mechanisms for “code review.” But the mostly widely practiced form of code review revolves around the patch and frequently is only productive when the original programmer is still around and still remembers how the code works. Having a reviewer read an entire program has been determined to be a frustrating and inordinately difficult thing to do—so instead, we focus on style and local structure and hope no one writes immaculate evil code. Security researchers may review code and look for patterns of use that developers tend to “get wrong” and zero in on them. We do have holistic standards, but they tend towards “it seems to work,” or, if we’re lucky, “it doesn’t break any automated regression tests.”

What we have is a critical communication failure.

One place to draw inspiration from is that of proof in mathematics. The proof has proven to be an useful tool at communicating mathematical ideas from one person to another, with a certain of rigor to avoid ambiguity and confusion, but not computer-level formality: unlike computer science, mathematicians have only recently begun to formalize proofs for computer consumption. Writing and reading proofs is tough business, but it is the key tool by which knowledge is passed down.

Is a program a proof? In short, yes. But it is a proof of the wrong thing: that is, it precisely specifies what the program will do, but subsequently fails to say anything beyond that (like correctness or performance or any number of other intangible qualities.) And furthermore, it is targeted at the computer, not another person. It is one of the reasons why “the specification of the language is the compiler itself” is such a highly unsatisfying answer.

Even worse, at some point in time you may have had in your head a mental model of how some dark magic worked, having meticulously worked it out and convinced yourself that it worked. And then you wrote // Black magic: don't touch unless you understand all of this! And then you moved on and the knowledge was lost forever, to be rediscovered by some intrepid soul who arduously reread your code and reconstructed your proof. Give them a bone! And if you haven’t even convinced yourself that the code for your critical section will do the right thing, shame on you! (If your code is simple, it should have been a simple proof. If your code is complicated, you probably got it wrong.)

You might argue that this is just the age-old adage “we need more documentation!” But there is a difference: proofs play a fundamentally different role than just documentation. Like programs, they must also be maintained, but their maintenance is not another chore to be done, inessential to the working of your program—rather, it should be considered a critical design exercise for assuring you and your colleagues of that your new feature is theoretically sound. It is stated that good comments say “Why” not “What.” I want to demand rigor now.

Rigor does not mean that a proof needs to be in “Greek letters” (that is, written in formal notation)—after all, such language is frequently off putting to those who have not seen it before. But it’s often a good idea, because formal language can capture ideas much more precisely and succinctly than English can.

Because programs frequently evolve in their scope and requirements (unlike mathematical proofs), we need unusually good abstractions to make sure we can adjust our proofs. Our proofs about higher level protocols should be able to ignore the low level details of any operation. Instead, they should rely on whatever higher level representation each operation has (whether its pre and post-conditions, denotational semantics, predicative semantics, etc). We shouldn’t assume our abstractions work either (nor should we throw up our hands and say “all abstractions are leaky”): we should prove that they have the properties we think they should have (and also say what properties they don’t have too). Of course, they might end up being the wrong properties, as is often the case in evolutionary software, but often, proof can smoke these misconceptions out.

October 18, 2010I’ve been having some vicious fun over the weekend hacking up a little tool called MMR Hammer in Haskell. I won’t bore you with the vagaries of multimaster replication with Fedora Directory Server; instead, I want to talk about rapidly prototyping scripts in Haskell—programs that are characterized by a low amount of computation and a high amount of IO. Using this script as a case study, I’ll describe how I approached the problem, what was easy to do and what took a little more coaxing. In particular, my main arguments are:

- In highly specialized scripts, you can get away with not specifying top-level type signatures,

- The IO monad is the only monad you need, and finally

- You can and should write hackish code in Haskell, and the language will impose just the right amount of rigor to ensure you can clean it up later.

I hope to convince you that Haskell can be a great language for prototyping scripts.

What are the characteristics of rapidly prototyping scripts? There are two primary goals of rapid prototyping: to get it working, and to get it working quickly. There are a confluence of factors that feed into these two basic goals:

- Your requirements are immediately obvious—the problem is an exercise of getting your thoughts into working code. (You might decide later that your requirements are wrong.)

- You have an existing API that you want to use, which let’s you say “I want to set the X property to Y” instead of saying “I will transmit a binary message of this particular format with this data over TCP.” This should map onto your conception of what you want to do.

- You are going to manually test by repeatedly executing the code path you care about. Code that you aren’t developing actively will in general not get run (and may fail to compile, if you have lots of helper functions). Furthermore, running your code should be fast and not involve a long compilation process.

- You want to avoid shaving yaks: solving unrelated problems eats up time and prevents your software from working; better to hack around a problem now.

- Specialization of your code for your specific use-case is good: it makes it easier to use, and gives a specific example of what a future generalization needs to support, if you decide to make your code more widely applicable in the future (which seems to happen to a lot of prototypes.)

- You’re not doing very much computationally expensive work, but your logic is more complicated than is maintainable in a shell script.

What does a language that enables rapid prototyping look like?

- It should be concise, and at the very least, not make you repeat yourself.

- It should “come with batteries,” and at least have the important API you want to use.

- It should be interpreted.

- It should be well used; that is, what you are trying to do should exist somewhere in the union of what other people have already done with the language. This means you are less likely to run into bizarre error conditions in code that no one else runs.

- It should have a fast write-test-debug cycle, at least for small programs.

- The compiler should not get in your way.

General prototyping in Haskell. If we look at our list above, Haskell has several aspects that recommend it. GHC has a runghc command which allows you to interpret your script, which means for quick prototyping. Functional programming encourages high amounts of code reuse, and can be extremely concise when your comfortable with using higher-order functions. And, increasingly, it’s growing a rather large set of batteries. In the case of LDAP MMR, I needed a bindings for the OpenLDAP library, which John Goerzen had already written. A great start.

The compiler should not get in your way. This is perhaps the most obvious problem for any newcomer to Haskell: they try to some pedestrian program and the compiler starts bleating at them with a complex type error, rather than the usual syntax error or runtime error. As they get more acquainted with Haskell, their mental model of Haskell’s type system improves and their ability to fix type errors improves.

The million dollar question, then, is how well do you have to know Haskell to be able to quickly resolve type errors? I argue, in the case of rapid prototyping in Haskell, not much at all!

One simplifying factor is the fact that the functions you write will usually not be polymorphic. Out of the 73 fully implemented functions in MMR Hammer, only six have inferred nontrivial polymorphic type signatures, all but one of these is only used single type context.

For these signatures, a is always String:

Inferred type: lookupKey :: forall a.

[Char] -> [([Char], [a])] -> [a]

Inferred type: lookupKey1 :: forall a.

[Char] -> [([Char], [a])] -> Maybe a

m is always IO, t is always [String] but is polymorphic because it’s not used in the function body:

Inferred type: mungeAgreement :: forall (m :: * -> *).

(Monad m) =>

LDAPEntry -> m LDAPEntry

Inferred type: replicaConfigPredicate :: forall t (m :: * -> *).

(Monad m) =>

([Char], t) -> m Bool

a here is always (String, String, String); however, this function is one of the few truly generic ones (it’s intended to be an implementation of msum for IO):

Inferred type: tryAll :: forall a. [IO a] -> IO a

And finally, our other truly generic function, a convenience debugging function:

Inferred type: debugIOVal :: forall b. [Char] -> IO b -> IO b

I claim that for highly specific, prototype code, GHC will usually infer fairly monomorphic types, and thus you don’t need to add very many explicit type signatures to get good errors. You may notice that MMR Hammer has almost no explicit type signatures—I argue that for monomorphic code, this is OK! Furthermore, this means that you only need to know how to use polymorphic functions, and not how to write them. (To say nothing of more advanced type trickery!)

Monads, monads, monads. I suspect a highly simplifying assumption for scripts is to avoid using any monad besides IO. For example, the following code could have been implemented using the Reader transformer on top of IO:

ldapAddEntry ldap (LDAPEntry dn attrs) = ...

ldapDeleteEntry ldap (LDAPEntry dn _ ) = ...

printAgreements ldap = ...

suspendAgreements ldap statefile = ...

restoreAgreements ldap statefile = ...

reinitAgreements ldap statefile = ...

But with only one argument being passed around, which was essentially required for any call to the API (so I would have done a bit of ask calling anyway), so using the reader transformer would have probably increased code size, as all of my LDAP code would have then needed to be lifted with liftIO.

Less monads also means less things to worry about: you don’t have to worry about mixing up monads and you can freely use error as a shorthand for bailing out on a critical error. In IO these get converted into exceptions which are propagated the usual way—because they are strings, you can’t write very robust error handling code, but hey, prototypes usually don’t have error handling. In particular, it’s good for a prototype to be brittle: to prefer to error out rather than to do some operation that may be correct but could also result in total nonsense.

Hanging lambda style also makes writing out code that uses bracketing functions very pleasant. Here are some example:

withFile statefile WriteMode $ \h ->

hPutStr h (serializeEntries replicas)

forM_ conflicts $ \(LDAPEntry dn attrs) ->

putStrLn dn

Look, no parentheses!

Reaping the benefits. Sometimes, you might try writing a program in another language for purely pedagogical purposes. But otherwise, if you know a language, and it works well for you, you won’t really want to change unless there are compelling benefits. Here are the compelling benefits of writing your code in Haskell:

When you’re interacting with the outside world, you will fairly quickly find yourself wanting some sort of concurrent execution: maybe you want to submit a query but timeout if it doesn’t come back in ten seconds, or you’d like to do several HTTP requests in parallel, or you’d like to monitor a condition until it is fulfilled and then do something else. Haskell makes doing this sort of thing ridiculously easy, and this is a rarity among languages that can also be interpreted.

Because you don’t have automatic tests, once you’ve written some code and manually verified that it works, you want it to stay working even when you’re working on some other part of the program. This is hard to guarantee if you’ve built helper functions that need to evolve: if you change a helper function API and forget to update all of its call sites, your code will compile but when you go back and try running an older codepath you’ll find you’ll have a bunch of trivial errors to fix. Static types make this go away. Seriously.

Haskell gives you really, really cheap abstraction. Things you might have written out in full back in Python because the more general version would have required higher order functions and looked ugly are extremely natural and easy in Haskell, and you truly don’t have to say very much to get a lot done. A friend of mine once complained that Haskell encouraged you to spend to much time working on abstractions; this is true, but I also believe once you’ve waded into the fields of Oleg once, you’ll have a better feel in the future for when it is and isn’t appropriate.

Rigorous NULL handling with Maybe gets you thinking about error conditions earlier. Many times, you will want to abort because you don’t want to bother dealing with that error condition, but other times you’ll want to handle things a little more gracefully, and the explicit types will always remind you when that is possible:

case mhost of

(Just host) -> do

let status = maybe "no status found" id mstatus

printf ("%-" ++ show width ++ "s : %s\n") host status

_ -> warnIO ("Malformed replication agreement at " ++ dn)

Slicing and dicing input in a completely ad hoc way is doable and concise:

let section = takeWhile (not . isPrefixOf "profile") . tail

. dropWhile (/= "profile default") $ contents

getField name = let prefix = name ++ " "

in evaluate . fromJust . stripPrefix prefix

. fromJust . find (isPrefixOf prefix)

$ section

But at the same time, it’s not too difficult to rip out this code for a real parsing library for not too many more lines of code. This an instance of a more general pattern in Haskell, which is that moving from brittle hacks to robust code is quite easy to do (see also, static type system.)

Some downsides. Adding option parsing to my script was unreasonably annoying, and after staring at cmdargs and cmdlib for a little bit, I decided to roll my own with getopt, which ended up being a nontrivial chunk of code in my script anyway. I’m not quite sure what went wrong here, but part of the issue was my really specialized taste in command line APIs (based off of Git, no less), and it wasn’t obvious how to use the higher level libraries to the effect I wanted. This is perhaps witnessed by the fact that most of the major Haskell command line applications also roll their own command parser. More on this on another post.

Using LDAP was also an interesting exercise: it was a fairly high quality library that worked, but it wasn’t comprehensive (I ended up submitting a patch to support ldap_initialize) and it wasn’t battle tested (it had no workaround for a longstanding bug between OpenLDAP and Fedora DS—more on that in another post too.) This is something that gets better with time, but until then expect to work closely with upstream for specialized libraries.

October 15, 2010This post is for those of you have always wondered why we have a forall keyword in Haskell but no exists keyword. Most of the existing tutorials on the web take a very operational viewpoint to what an existential type is, and show that placing the forall in the “right place” results in the correct behavior. I’m going to take a different approach and use the Curry-Howard isomorphism to explain the translation. Some of the logic examples are shamelessly stolen from Aaron Coble’s Logic and Proof lecture notes.

First, a little logic brush up. (Feel free to skip.)

At the very bottom of the hierarchy of logic systems lies propositional logic. Whenever you write a non-polymorphic function in Haskell, your function definition corresponds to a statement in propositional logic—this is the simply typed lambda calculus. You get some propositional symbols P, Q and R (corresponding to types) and some logical connectives $\lnot \land \lor \to \iff$. In particular, $\to$ corresponds to the function arrow ->, so you can read $P \to Q$ as the type P -> Q.

$\forall xy.\ P(x) = P(y)$

The next step up is first-order predicate logic, which allows you to use the quantifiers ∀ and ∃ on variables ranging over individuals x, y and z (the predicates take individuals and return propositions). Logical formulas in this system start to look a lot like Haskell polymorphism, but it actually corresponds to dependent types: individuals are terms, not types.

For the purpose of this post, we’ll instead have x, y and z to range over propositions (types), except for two examples of first order logic to get some intuition for quantifiers. Then polymorphic function definitions are statements in what is called propositional second order logic.

Propositional second order logic gives us a bit of rope, and we can do some fairly unintuitive things with it. Existential types are one such application. However, most Haskellers have a pretty good intuition for polymorphic functions like id :: a -> a, which actually have an ∀ quantifier at the very beginning, like id :: forall a. a -> a or $\forall x. x \to x$. What I’d like to do next is make the connection between our intuitive sense of polymorphic functions and our intuitive sense of a universal quantifier.

Consider the following English sentence: All professors can teach and do research. We can translate this into a statement in first-order logic (x ranging over individuals):

$\forall x.\ \mathrm{professor}(x) \to \mathrm{teaches}(x) \land \mathrm{researches}(x)$

The intuition for the trick of “narrowing” a universally quantified variable by placing it in an implication corresponds directly to the implicit dictionary passing that occurs when you use a type class (which also narrows a universally quantified variable).

We can do similar translations for the existential quantifier. Everybody loves somebody and there is somebody that everybody loves correspond to, respectively:

$\forall x\ \exists y\ \mathrm{loves}(x, y)$

$\exists y\ \forall x\ \mathrm{loves}(x, y)$

Take a moment to convince yourself that these are not the same statements, and figure out which direction implication goes.

We’ll now jump straight to the implication equivalences, which are the punchline, so to speak. Here, x ranges over propositions (i.e. types).

$(\exists x\ A[x]) \to B \equiv \forall x\ (A[x] \to B)$

$(\forall x\ A[x]) \to B \equiv \exists x\ (A[x] \to B)$

Consider the first equivalence: intuitively, it states that we can simulate a function that takes an existential type by using forall x. (A x -> B). This is precisely the existential data constructor:

data OpaqueBox = forall a. OpaqueBox a

which has the type forall a. (a -> OpaqueBox).

The second proposition is a little trickier to grasp: in the right to left direction, it seems clear that if there exists an inference A(x) to B for some x, if I provide all x I will get B. However, from left to right, if I provide all A(x) to get B, one of those A(x) will have to have been used but I have no good way of figuring out which one.

We can rigorously prove this equivalence with sequent calculus. We can think of these as “deduction rules” much like modus ponens (if A then B, A; therefore, B). However, statements in the sequent calculus take the form $\Gamma \vdash \Delta$, where Γ is the set of propositions which conjunctively form the assumption, and Δ is the set of propositions which disjunctively form the result. (The $\vdash$ is called a “turnstile” and indicates implication.)

$\cfrac{\Gamma \vdash A, \Delta \qquad \Sigma, B \vdash \Pi}{\Gamma, \Sigma, A\rightarrow B \vdash \Delta, \Pi} \quad ({\rightarrow }L)$ $\cfrac{\Gamma, A \vdash B, \Delta}{\Gamma \vdash A \rightarrow B, \Delta} \quad ({\rightarrow}R)$

$\cfrac{\Gamma, A[t/x] \vdash \Delta}{\Gamma, \forall x A \vdash \Delta} \quad ({\forall}L)$ $\cfrac{\Gamma \vdash A[y/x], \Delta}{\Gamma \vdash \forall x A, \Delta} \quad ({\forall}R)$

$\cfrac{\Gamma, A[y/x] \vdash \Delta}{\Gamma, \exists x A \vdash \Delta} \quad ({\exists}L)$ $\cfrac{\Gamma \vdash A[t/x], \Delta}{\Gamma \vdash \exists x A, \Delta} \quad ({\exists}R)$

$\forall L$ and $\exists R$, in particular, are quite interesting: $\forall L$ says I can make any assumed proposition “polymorphic” by picking some subterm and replacing all instances of it with a newly universally quantified variable (it’s a stronger assumption, so we’re weakening our entailment). We can indeed do this in Haskell (as one might transform (Int -> Bool) -> Int -> Bool into (a -> b) -> a -> b), so long as our proof doesn’t peek at the actual type to perform its computation. $\exists R$, on the other hand, says that I can take any resulting proposition and “hide” my work by saying something weaker: instead of A[t], I merely say there exists some x for which A[x] is true. This corresponds nicely to the intuition of an existential type hiding representation. Another nice duality is that universal quantification hides information inside the proof, while existential quantification hides information outside of the proof.

$\forall R$ and $\exists L$ don’t do as much work, but they are a little tricky to use: any universal quantification on the right side of the turnstile can create/destroy a free variable, and any existential quantification on the left side can create/destroy a free variable. Note that $\forall L$ and $\exists R$ cannot be used this way; while they can use existing free variables, they can’t create or destroy them.

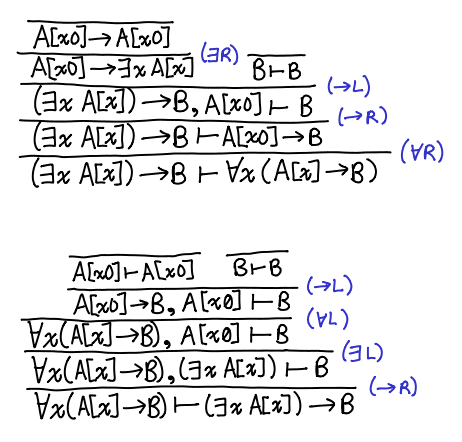

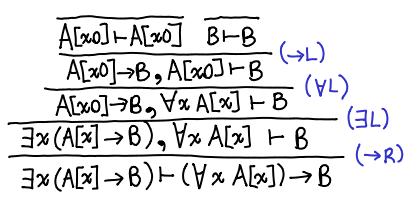

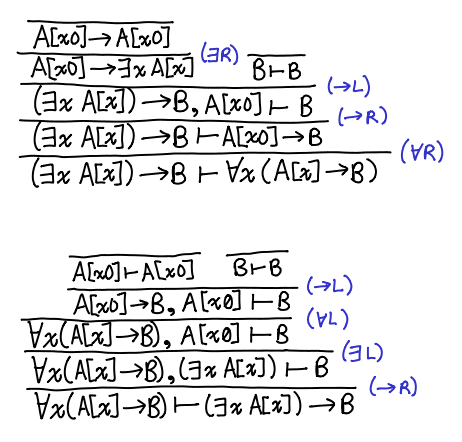

Here is the proof in both directions of the equivalence. What we’re trying to prove lives on the bottom; tautologies are at the top.

The proofs are nicely symmetrical: one uses ∀L and ∃L, and the other ∀R and ∃R. The application of the →R “uncurries” each entailment. Furthermore, the fact that both proofs are constructive indicates that there is this equivalence is one that can be witnessed by a Haskell program! You can check out a Coq version of the proof from kmc.

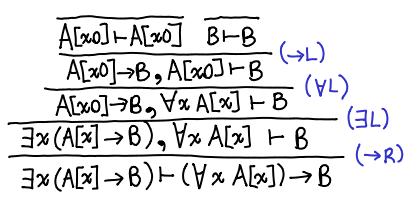

Postscript. I picked the wrong equivalence initially, but I felt it would be a shame not to share it. Here is the proof for: $\exists x\ (A[x] \to B) \vdash (\forall x\ A[x]) \to B$.

This is done entirely with intuitionistic logic: the other direction requires classical logic. This is left as an exercise for the reader, the solution is here by monochrom. There is also a version from kmc in Coq in both directions. This result has an interesting implication for existentials over functions: we can translate from an existential to a universal, but not back!