December 21, 2010I will be in the following places at the following times:

- Paris up until evening of 12/22

- Berlin from 12/23 to 12/24

- Dresden on 12/24

- Munich from 12/25 to 12/26

- Zurich on 12/27

- Lucerne from 12/28 to 12/29

Plans over the New Year are still a little mushy, so I’ll post another update then. Let me know if you’d like to meet up!

Non sequitur. I went to the Mondrian exhibition at Centre Pompidou, and this particular gem, while not in the exhibition itself (it was in the female artists collection), I couldn’t resist snapping a photo of.

December 20, 2010What semantics has to say about specifications

Conventional wisdom is that premature generalization is bad (architecture astronauts) and vague specifications are appropriate for top-down engineering but not bottom-up. Can we say something a little more precise about this?

Semantics are formal specifications of programming languages. They are perhaps some of the most well-studied forms of specifications, because computer scientists love tinkering with the tools they use. They also love having lots of semantics to pick from: the more the merrier. We have small-step and big-step operational semantics; we have axiomatic semantics and denotational semantics; we have game semantics, algebraic semantics and concurrency semantics. Describing the programs we actually write is difficult business, and it helps to have as many different explanations as possible.

In my experience, it’s rather rare to see software have multiple specifications, each of them treated equally. Duplication makes it difficult to evolve the specification as more information becomes available and requirements change (as if it wasn’t hard enough already!) Two authoritative sources can conflict with each other. One version of the spec may dictate how precisely one part of the system is to be implemented, where the other leaves it open (up to some external behavior). What perhaps is more common is a single, authoritative specification, and then a constellation of informative references that you might actually refer to on a day-to-day basis.

Of course, this happens in the programming language semantics world all the time. On the subject of conflicts and differing specificity, here are two examples from denotational semantics (Scott semantics) and game semantics.

Too general? Here, the specification allows for some extra behavior (parallel or in PCF) that is impossible to implement in the obvious way (sequentially). This problem puzzled researchers for some time: if the specification is too relaxed, do you add the feature that the specification suggests (PCF+por), or do you attempt to modify the semantics so that this extra behavior is ruled out (logical relations)? Generality can be good, but it frequently comes at the cost of extra implementation complexity. In the case of parallel or, however, this implementation complexity is a threaded runtime system, which is useful for unrelated reasons.

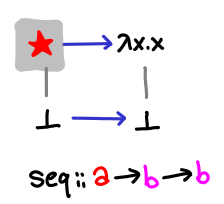

Too vague? Here, the specification fails to capture a difference in behavior (seq and pseq are (Scott) semantically equivalent) that happens to be important operationally speaking (control of evaluation order). Game semantics neatly resolves this issue: we can distinguish between x `pseq` y and y `pseq` x because in the corresponding conversation, the expression asks for the value of x first in the former example, and the value of y first in the latter. However, vague specifications give more latitude to the compiler for optimizations.

Much like the mantra “the right language for the job”, I suspect there is a similar truth in “the right style of specification for the job.” But even further than that, I claim that looking at the same domain from different perspectives deepens your understanding of the domain itself. When using semantics, one includes some details and excludes others: as programmers we do this all the time—it’s critical for working on a system of any sort of complexity. When building semantics, the differences between our semantics give vital hints about the abstraction boundaries and potential inconsistencies in our original goals.

There is one notable downside to a lot of different paradigms for thinking about computation: you have to learn all of them! Axiomatic semantics recall the symbolic manipulation you might remember from High School maths: mechanical and not very interesting. Denotational semantics requires a bit of explaining before you can get the right intuition for it. Game semantics as “conversations” seems rather intuitive (to me) but there are a number of important details that are best resolved with some formality. Of course, we can always fall back to speaking operationally, but it is an approach that doesn’t scale for large systems (“read the source”).

December 17, 2010In which Edward travels France

Many, many years ago, I decided that I would study French rather than Spanish in High School. I wasn’t a particularly driven foreign language learner: sure I studied enough to get As (well, except for one quarter when I got a B+), but I could never convince myself to put enough importance on absorbing as much vocabulary and grammar as possible. Well, now I’m in France and this dusty, two-year old knowledge is finally being put to good use. And boy, am I wishing that I’d paid more attention in class.

Perhaps the first example of my fleeting French knowledge was when we reached the Marseille airport and I went up to the ticket counter and said, “Excusez-moi, je voudrais un… uhh…” the word for map having escaped my mind. I tried “carte” but that wasn’t quite correct. The agent helpfully asked me in English if I was looking for a map, to which I gratefully answered yes. Turns out the word is “plan.” I thanked the agent and consequently utterly failed to understand the taxi driver who took us to our first night’s accommodation in Plan-de-Cuques.

Still, my broken, incomplete knowledge of French was still better than none at all, and I soon recall enough about the imperatif and est-ce que to book a taxi, complain about coffee and tea we were served at Le Moulin Bleu (Tea bags? Seriously? Unfortunately, I was not fluent enough to get us a refund), and figure out what to do when we accidentally missed our bus stop (this involved me remembering what an eglise was). Though, I didn’t remember until Monday that Mercredi was Wednesday, not Monday.

Our itinerary involved staying in a few small French villages for the first few days, and then moving into the bigger cities (Lyon and Paris). Exploring small villages is a bit challenging, since the percentage of English speakers is much smaller and it’s easy to accidentally bus out to a town and find out that all of the stores are closed because it’s Monday and of course everything is closed on Monday! But there are also chances to be lucky: wandering out without any particular destination in mind, we managed to stumble upon a charming Christmas market and spontaneously climbed up a hill to a fantastic view of Marseilles.

Walking around in cold, subzero (Celsius) weather with your travel mates who have varying degrees of tolerance for physical exertion and the cold makes you empathize a bit with what your parents might have felt trucking you around as a kid during a vacation. After visiting the Basilica of Notre Dame in Lyon, I was somewhat at a loss for what to do next: the trip for shopping was a flop (none of us were particularly big shoppers), it was cold outside and the group didn’t have a particularly high tolerance for aimlessly wandering around a city. Spontaneity is difficult in a group. But it can happen, as it did when we trekked up to Tête d’Or and then cycled around with the Velo bike rent service (it’s “free” if you bike a half hour or less, but you have to buy a subscription, which for 1-day is one euro. Still quite a bargain.)

Teaching my travel mates phrases in French lead to perhaps one of the most serendipitous discoveries we made while at Lyon. We were up at Croix-de-Rousse at the indoors market, and it was 6:00; a plausible time for us British and American tourists to be thinking about dinner. I had just taught one of my travel mates how to ask someone if they spoke English (Vous parlez Anglais?) and she decided to find someone around who spoke English to ask for restaurant recommendations. The first few tries were a flop, but then we encountered an extremely friendly German visitor who was accompanied by a French native, and with it we got some restaurant recommendations, one of which was Balthaz’art, a pun on Balthasaur. After embarassingly banging on the door and being told they didn’t open until 7:30pm (right, the French eat dinner late), we decided to stick it out.

And boy was it worth it.

As for the title, noting the length of my blog posts, one of my MIT friends remarked, “Do you, like, do anything other than write blog posts these days?” To which I replied, “Tourist by day, Blogger by night”—since unlike many bloggers, I have not had the foresight to write up all of the posts for the next month in advance. Indeed, I need to go to sleep soon, since as of the time of writing (late Wednesday night), we train out to France tomorrow. Bonsoir, or perhaps for my temporally displaced East Coast readers, bonjour!

Photo credits. I nicked the lovely photo of Plan-de-Cuques from Gloria’s album. I’m still in the habit of being very minimalist when it comes to taking photos. (Stereotype of an Asian tourist! Well, I don’t do much better with my incredibly unchic ski jacket and snow pants.)

December 15, 2010New to this series? Start at the beginning!.

Today we’re going to take a closer look at a somewhat unusual data type, Omega. In the process, we’ll discuss how the lub library works and how you might go about using it. This is of practical interest to lazy programmers, because lub is a great way to modularize laziness, in Conal’s words.

Omega is a lot like the natural numbers, but instead of an explicit Z (zero) constructor, we use bottom instead. Unsurprisingly, this makes the theory easier, but the practice harder (but not too much harder, thanks to Conal’s lub library). We’ll show how to implement addition, multiplication and factorial on this data type, and also show how to prove that subtraction and equality (even to vertical booleans) are uncomputable.

This is a literate Haskell post. Since not all methods of the type classes we want to implement are computable, we turn off missing method warnings:

> {-# OPTIONS -fno-warn-missing-methods #-}

Some preliminaries:

> module Omega where

>

> import Data.Lub (HasLub(lub), flatLub)

> import Data.Glb (HasGlb(glb), flatGlb)

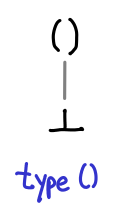

Here is, once again, the definition of Omega, as well as two distinguished elements of it, zero and omega (infinity.) Zero is bottom; we could have also written undefined or fix id. Omega is the least upper bound of Omega and is an infinite stack of Ws. :

> data Omega = W Omega deriving (Show)

>

> zero, w :: Omega

> zero = zero

> w = W w -- the first ordinal, aka Infinity

Here are two alternate definitions of w:

w = fix W

w = lubs (iterate W zero)

The first alternate definition writes the recursion with an explicit fixpoint, as we’ve seen in the diagram. The second alternate definition directly calculates ω as the least upper bound of the chain [⊥, W ⊥, W (W ⊥) ...] = iterate W ⊥.

What does the lub operator in Data.Lub do? Up until now, we’ve only seen the lub operator used in the context of defining the least upper bound of a chain: can we usefully talk about the lub of two values? Yes: the least upper bound is simply the value that is “on top” of both the values.

If there is no value on top, the lub is undefined, and the lub operator may give bogus results.

If one value is strictly more defined than another, it may simply be the result of the lub.

An intuitive way of thinking of the lub operator is that it combines the information content of two expressions. So (1, ⊥) knows about the first element of the pair, and (⊥, 2) knows about the second element, so the lub combines this info to give (1, 2).

How might we calculate the least upper bound? One thing to realize is that in the case of Omega, the least upper bound is in fact the max of the two numbers, since this domain totally ordered. :

> instance Ord Omega where

> max = lub

> min = glb

Correspondingly, the minimum of two numbers is the greatest lower bound: a value that has less information content than both values.

If we think of a conversation that implements case lub x y of W a -> case a of W _ -> True, it might go something like this:

Me

Lub, please give me your value.

Lub

Just a moment. X and Y, please give me your values.

X

My value is W and another value.

Lub

Ok Edward, my value is W and another value.

Me

Thanks! Lub, what’s your next value?

Lub

Just a moment. X, please give me your next value.

Y

(A little while later.) My value is W and another value.

Lub

Ok. Y, please give me your next value.

Y

My next value is W and another value.

Lub

Ok Edward, my value is W and another value.

Me

Thanks!

X

My value is W and another value.

Lub

Ok.

Here is a timeline of this conversation:

There are a few interesting features of this conversation. The first is that lub itself is lazy: it will start returning answers without knowing what the full answer is. The second is that X and Y “race” to return a particular W, and lub will not act on the result that comes second. However, the ordering doesn’t matter, because the result will always be the same in the end (this will not be the case when the least upper bound is not defined!)

The unamb library that powers lub handles all of this messy, concurrency business for us, exposing it with the flatLub operator, which calculates the least upper bound for a flat data type. We need to give it a little help to calculate it for a non-flat data type (although one wonders if this could not be automatically derivable.) :

> instance Enum Omega where

> succ = W

> pred (W x) = x -- pred 0 = 0

> toEnum n = iterate W zero !! n

>

> instance HasLub Omega where

> lub x y = flatLub x y `seq` W (pred x `lub` pred y)

An equivalent, more verbose but more obviously correct definition is:

isZero (W _) = False -- returns ⊥ if zero (why can’t it return True?)

lub x y = (isZero x `lub` isZero y) `seq` W (pred x `lub` pred y)

It may also be useful to compare this definition to a normal max of natural numbers:

data Nat = Z | S Nat

predNat (S x) = x

predNat Z = Z

maxNat Z Z = Z

maxNat x y = S (maxNat (predNat x) (predNat y))

We can split the definition of lub into two sections: the zero-zero case, and the otherwise case. In maxNat, we pattern match against the two arguments and then return Z. We can’t directly pattern match against bottom, but if we promise to return bottom in the case that the pattern match succeeds (which is the case here), we can use seq to do the pattern match. We use flatLub and lub to do multiple pattern matches: if either value is not bottom, then the result of the lub is non-bottom, and we proceed to the right side of seq.

In the alternate definition, we flatten Omega into Bool, and then use a previously defined lub instance on it (we could have also used flatLub, since Bool is a flat domain.) Why are we allowed to use flatLub on Omega, which is not a flat domain? There are two reasons: the first is that seq only cares about whether or not the its first argument is bottom or not: it implicitly flattens all domains into “bottom or not bottom.” The second reason is that flatLub = unamb, and though unamb requires the values on both sides of it to be equal (so that it can make an unambiguous choice between either one), there is no way to witness the inequality of Omega: both equality and inequality are uncomputable for Omega. :

> instance Eq Omega where -- needed for Num

The glb instance rather easy, and we will not dwell on it further. The reader is encouraged to draw the conversation diagram for this instance. :

> instance HasGlb Omega where

> glb (W x') (W y') = W (x' `glb` y')

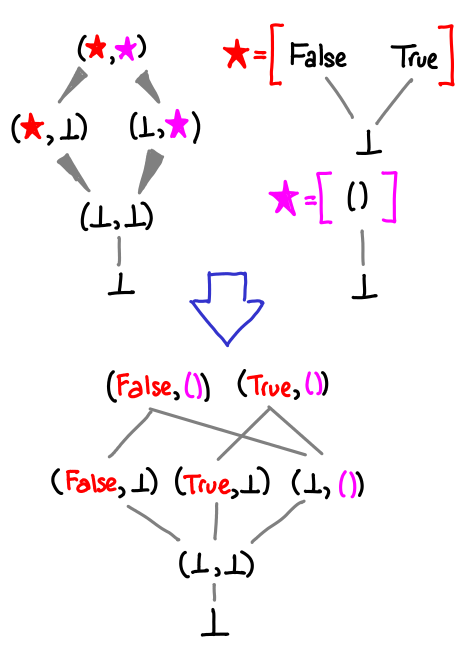

This is a good point to stop and think about why addition, multiplication and factorial are computable on Omega, but subtraction and equality are not. If you take the game semantics route, you could probably convince yourself pretty well that there’s no plausible conversation that would get the job done for any of the latter cases. Let’s do something a bit more convincing: draw some pictures. We’ll uncurry the binary operators to help the diagrams.

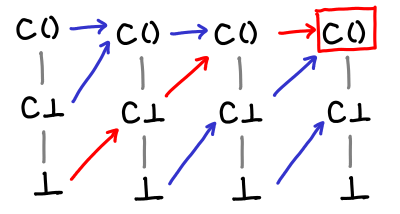

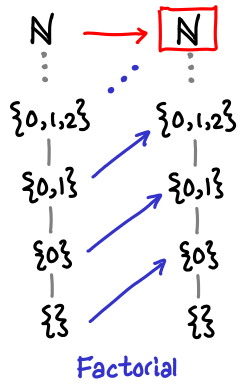

Here is a diagram for addition:

The pairs of Omega form a matrix (as usual, up and right are higher on the partial order), and the blue lines separate sets of inputs into their outputs. Multiplication is similar, albeit a little less pretty (there are a lot more slices).

We can see that this function is monotonic: once we follow the partial order into the next “step” across a blue line, we can never go back.

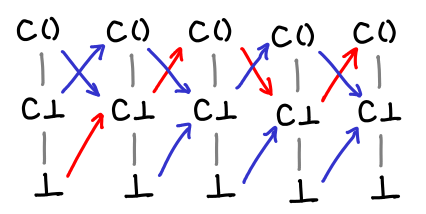

Consider subtraction now:

Here, the function is not monotonic: if I move right on the partial order and enter the next step, I can go “backwards” by moving up (the red lines.) Thus, it must not be computable.

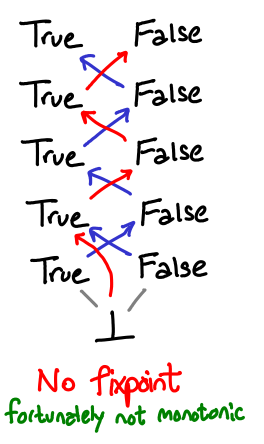

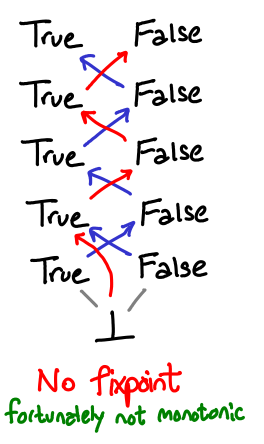

Here is the picture for equality. We immediately notice that mapping (⊥, ⊥) to True will mean that every value will have to map to True, so we can’t use normal booleans. However, we can’t use vertical booleans (with ⊥ for False and () for True) either:

Once again, you can clearly see that this function is not monotonic.

It is now time to actually implement addition and multiplication:

> instance Num Omega where

> x + y = y `lub` add x y

> where add (W x') y = succ (x' + y)

> (W x') * y = (x' * y) + y

> fromInteger n = toEnum (fromIntegral n)

These functions look remarkably similar to addition and multiplication defined on Peano natural numbers:

natPlus Z y = y

natPlus (S x') y = S (natPlus x' y)

natMul Z y = Z

natMul (S x') y = natPlus y (natMul x' y)

There is the pattern matching on the first zero as before. But natPlus is a bit vexing: we pattern match against zero, but return y: our seq trick won’t work here! However, we can use the observation that add will be bottom if its first argument is bottom to see that if x is zero, then the return value will be y. What if x is not zero? We know that add x y must be greater than or equal to y, so that works as expected as well.

We don’t need this technique for multiplication because zero times any number is zero, and a pattern match will do that automatically for us.

And finally, the tour de force, factorial:

factorial n = W zero `lub` (n * factorial (pred n))

We use the same trick that was used for addition, noting that 0! = 1. For factorial 1, both sides of the lub are in fact equal, and for anything bigger, the right side dominates.

To sum up the rules for converting pattern matches against zero into lubs (assuming that the function is computable):

f ⊥ = ⊥

f (C x') = ...

becomes:

f (C x') = ...

(As you may have noticed, this is just the usual strict computation). The more interesting case:

g ⊥ = c

g (C x') = ...

becomes:

g x = c `lub` g' x

where g' (C x') = ...

assuming that the original function g was computable (in particular, monotonic.) The case where x is ⊥ is trivial; and since ⊥ is at the bottom of the partial order, any possible value for g x where x is not bottom must be greater than or equal to bottom, fulfilling the second case.

A piece of frivolity. Quantum bogosort is a sorting algorithm that involves creating universes with all possible permutations of the list, and then destroying all universes for which the list is not sorted.

As it turns out, with lub it’s quite easy to accidentally implement the equivalent of quantum bogosort in your algorithm. I’ll use an early version of my addition algorithm to demonstrate:

x + y = add x y `lub` add y x

where add (W x') y = succ (x' + y)

Alternatively, (+) = parCommute add where:

parCommute f x y = f x y `lub` f y x

This definition gets the right answer, but needs exponentially many threads to figure it out. Here is a diagram of what is going on:

The trick is that we are repeatedly commuting the arguments to addition upon every recursion, and one of the nondeterministic paths leads to the result where both x and y are zero. Any other branch in the tree that terminates “early” will be less than the true result, and thus lub won’t pick it. Exploring all of these branches is, as you might guess, inefficient.

Next time, we will look at Scott induction as a method of reasoning about fixpoints like this one, relating it to induction on natural numbers and generalized induction. If I manage to understand coinduction by the next post, there might be a little on that too.

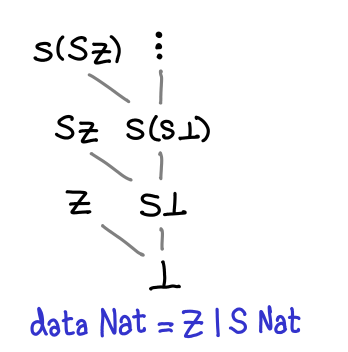

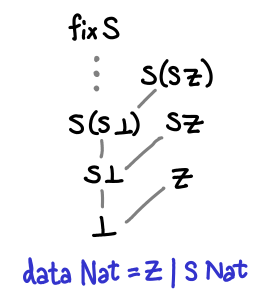

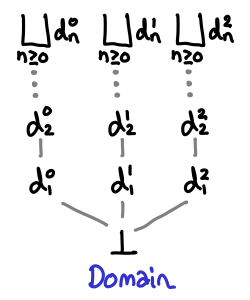

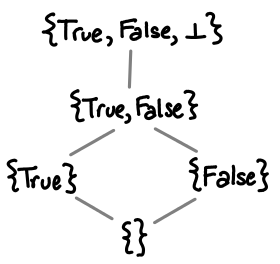

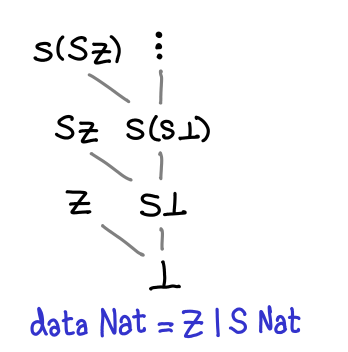

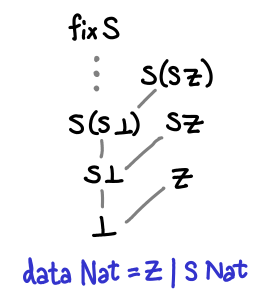

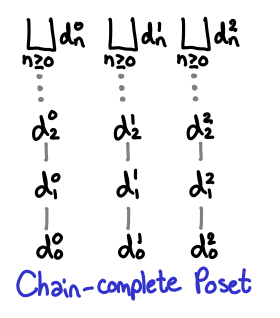

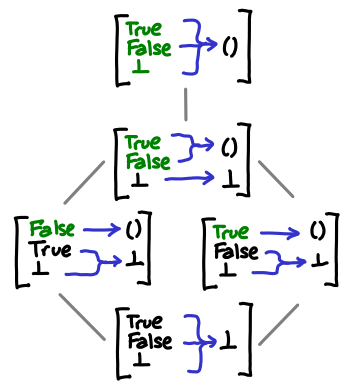

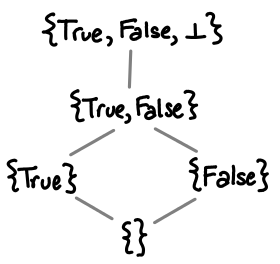

December 13, 2010Previously, we’ve drawn Hasse diagrams of all sorts of Haskell types, from data types to function types, and looked at the relationship between computability and monotonicity. In fact, all computable functions are monotonic, but not all monotonic functions are computable. Is there some description of functions that entails computability? Yes: Scott continuous functions. In this post, we look at the mathematical machinery necessary to define continuity. In particular, we will look at least upper bounds, chains, chain-complete partial orders (CPOs) and domains. We also look at fixpoints, which arise naturally from continuous functions.

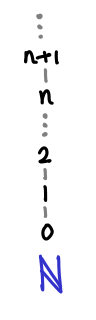

In our previous diagrams of types with infinitely many values, we let the values trail off into infinity with an ellipsis.

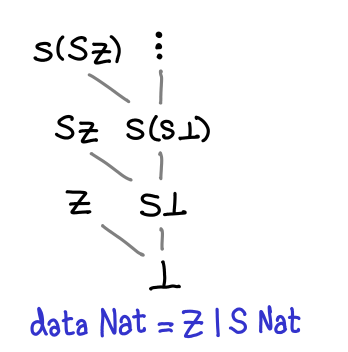

As several commentors have pointed out, this is not quite right: all Haskell data types also have a one or more top values, values that are not less than any other value. (Note that this is distinct from values that are greater than or equal to all other values: some values are incomparable, since these are partial orders we’re talking about.) In the case of Nat, there are a number of top values: Z, S Z, S (S Z), and so on are the most defined you can get. However, there is one more: fix S, aka infinity.

There are no bottoms lurking in this value, but it does seem a bit odd: if we peel off an S constructor (decrement the natural number), we get back fix S again: infinity minus one is apparently infinity.

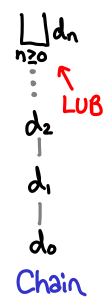

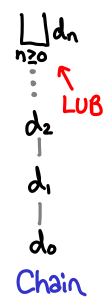

In fact, fix S is a least upper bound for the chain ⊥, S ⊥, S (S ⊥)… A chain is simply a sequence of values for which d_1 ≤ d_2 ≤ d_3 …; they are lines moving upwards on the diagrams we’ve drawn.

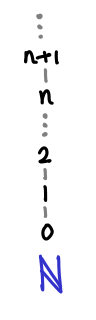

The least upper bound of a chain is just a value d which is bigger than all the members of the chain: it “sits at the top.” (For all n > 0, d_n ≤ d.) It is notated with a |_|, which is frequently called the “lub” operator. If the chain is strictly increasing, the least upper bound cannot be in the chain, because if it were, the next element in the chain would be greater than it.

A chain in a poset may not necessarily have a least upper bound. Consider the natural numbers with the usual partial ordering.

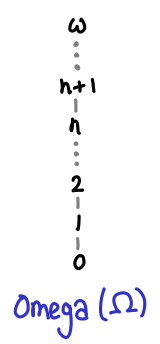

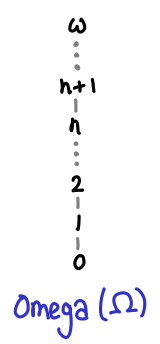

The chain 0 ≤ 1 ≤ 2 ≤ … does not have an upper bound, because the set of natural numbers doesn’t contain an infinity. We have to instead turn to Ω, which is the natural numbers and the smallest possible infinity, the ordinal ω.

Here the chain has a least upper bound.

Despite not having a lub for 0 ≤ 1 ≤ 2 ≤ …, the natural numbers have many least upper bounds, since every element n forms the trivial chain n ≤ n ≤ n…

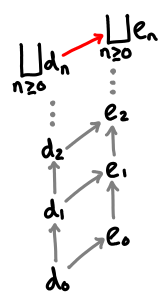

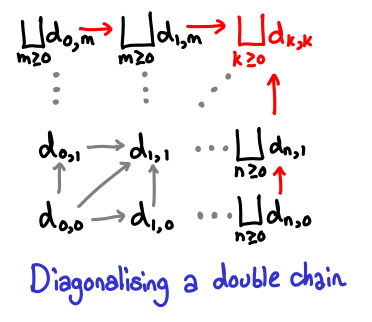

Here are pictorial representatios of some properties of lubs.

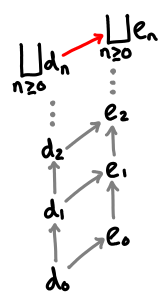

If one chain is always less than or equal to another chain, that chain’s lub is less than or equal to the other chain’s lub.

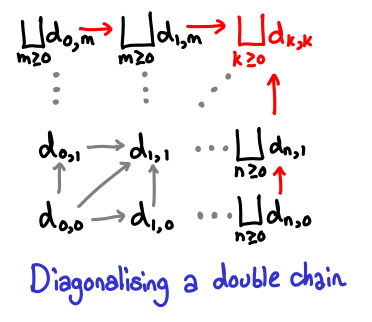

A double chain of lubs works the way you expect it to; furthermore, we can diagonalize this chain to get the upper bound in both directions.

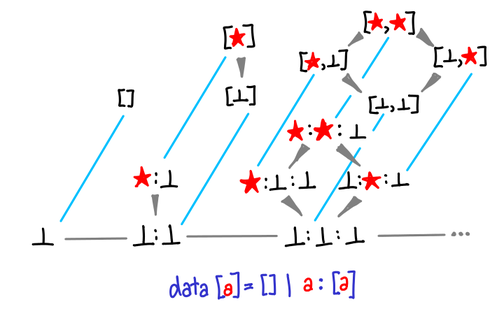

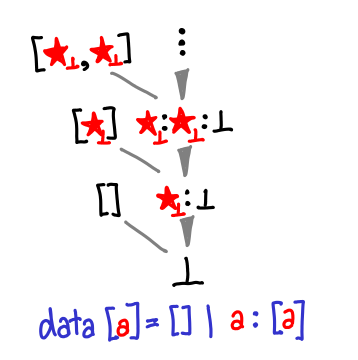

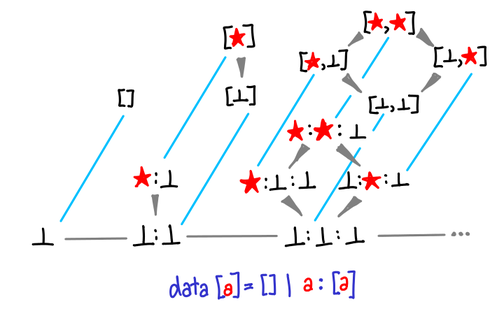

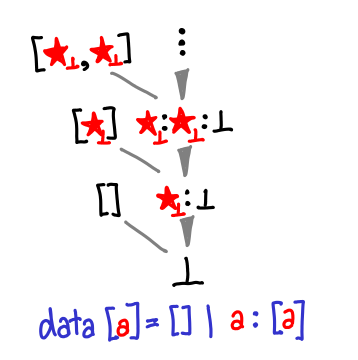

So, if we think back to any of the diagrams we drew previously, anywhere there was a “…’, in fact we could have placed an upper bound on the top of, courtesy of Haskell’s laziness. Here is one chain in the list type that has a least upper bound:

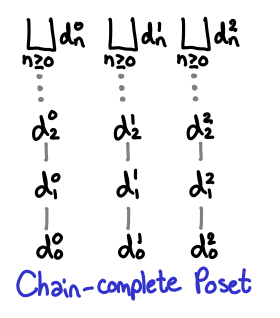

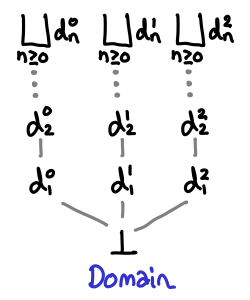

As we saw earlier, this is not always true for all partial orders, so we have a special name for posets that always have least upper bounds: chain-complete posets, or CPOs.

You may have also noticed that in every diagram, ⊥ was at the bottom. This too is not necessarily true of partial orders. We will call a CPO that has a bottom element a domain.

(The term domain is actually used quite loosely within the denotational semantics literature, many times having extra properties beyond the definition given here. I’m using this minimal definition from Marcelo Fiore’s denotational semantics lectures, and I believe that this is the Scott conception of a domain, although I haven’t verified this.)

So we’ve been in fact dealing with domains all this time, although we’ve been ignoring the least upper bounds. What we will find is that once we consider upper bounds we will find a stronger condition than monotonicity that entails computability.

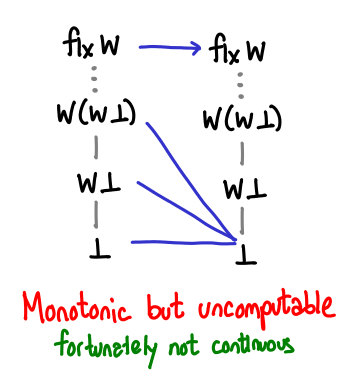

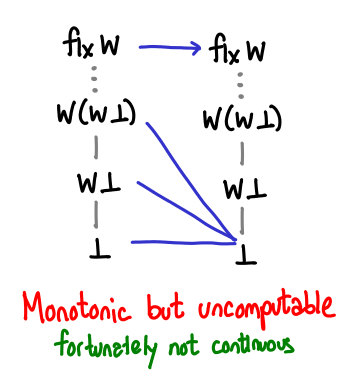

Consider the following Haskell data type, which represents the vertical natural numbers Omega.

Here is a monotonic function that is not computable.

Why is it not computable? It requires us to treat arbitrarily large numbers and infinity different: there is a discontinuity between what happens on finite natural numbers and what happens at infinity. Computationally, there is no way for us to check in finite time that any given value we have is actually infinity: we can only continually keep peeling off Ws and hope we don’t reach bottom.

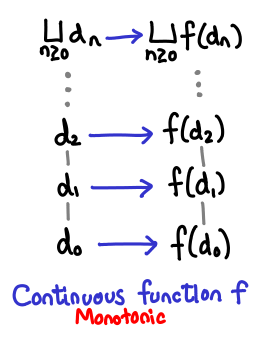

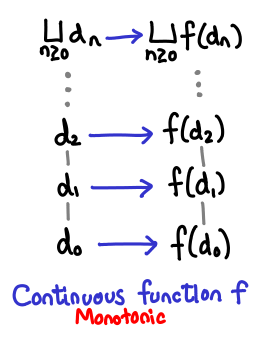

We can formalize this as follows: a function D -> D, where D is a domain, is continuous if it is monotonic and it preserves least upper bounds. This is not to say that the upper bounds all stay the same, but rather that if the upper bound of e_1 ≤ e_2 ≤ e_3 … is lub(e), then the upper bound of f(e_1) ≤ f(e_2) ≤ f(e_3) … is f(lub(e)). Symbolically:

$f(\bigsqcup_{n \ge 0} d_n) = \bigsqcup_{n \ge 0} f(d_n)$

Pictorially:

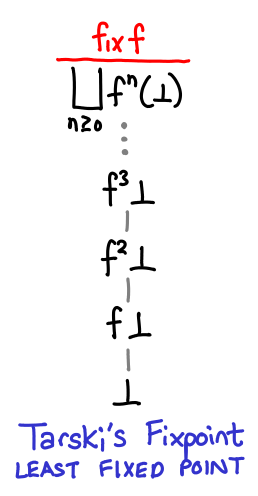

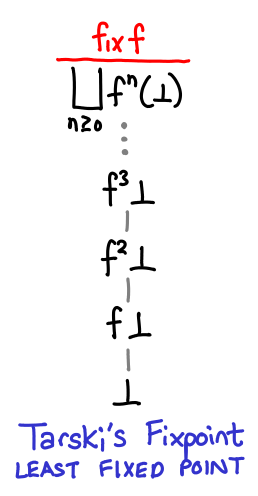

Now it’s time to look at fixpoints! We’ll jump straight to the punchline: Tarski’s fixpoint theorem states that the least fixed point of a continuous function is the least upper bound of the sequence ⊥ ≤ f(⊥) ≤ f(f(⊥)) …

Because the function is continuous, it is compelled to preserve this least upper bound, automatically making it a fixed point. We can think of the sequence as giving us better and better approximations of the fixpoint. In fact, for finite domains, we can use this fact to mechanically calculate the precise fixpoint of a function.

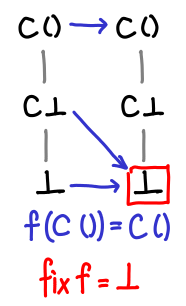

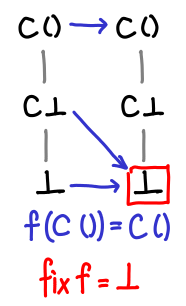

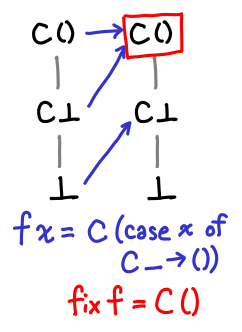

The first function we’ll look at doesn’t have a very interesting fixpoint.

If we pass bottom to it, we get bottom.

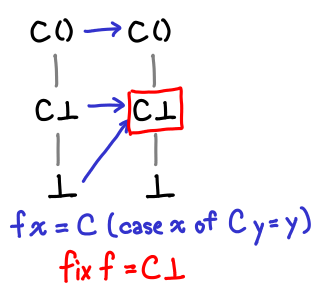

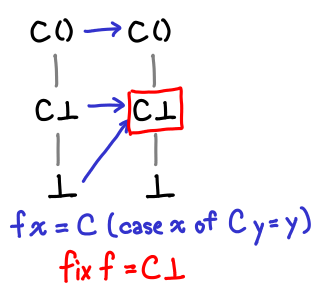

Here’s a slightly more interesting function.

It’s not obvious from the definition (although it’s more obvious looking at the Hasse diagrams) what the fixpoint of this function is. However, by repeatedly iterating f on ⊥, we can see what happens to our values:

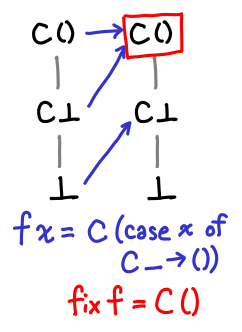

Eventually we hit the fixpoint! And even more importantly, we’ve hit the least fixpoint: this particular function has another fixpoint, since f (C ()) = C ().

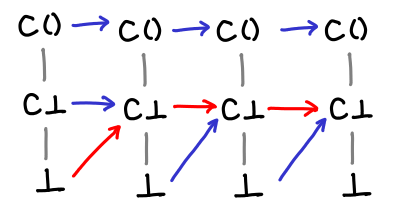

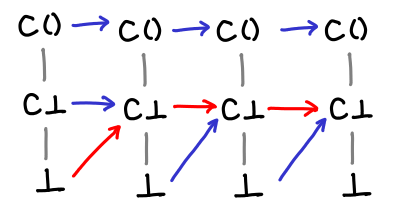

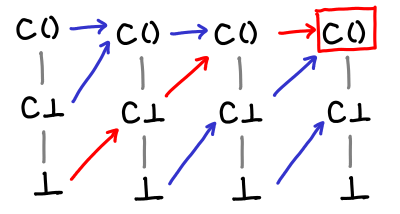

Here’s one more set for completeness.

We can see from this diagrams a sort of vague sense why Tarski’s fixpoint theorem might work: we gradually move up and up the domain until we stop moving up, which is by definition the fixpoint, and since we start from the bottom, we end up with the least fixed point.

There are a few questions to answer. What if the function moved the value down? Then we might get stuck in an infinite loop.

We’re safe, however, because any such function would violate monotonicity: a loop on e₁ ≤ e₂ would result in f(e₁) ≥ f(e₂).

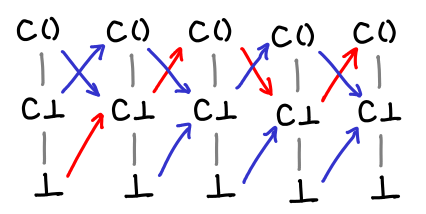

Our finite examples were also total orders: there was no branching of our diagrams. What if our function mapped a from one branch to another (a perfectly legal operation: think not)?

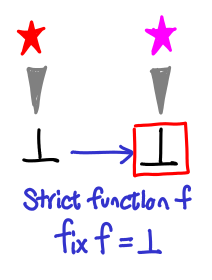

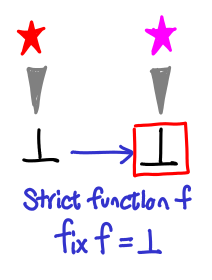

Fortunately, in order to get to such a cycle, we’d have to break monotonicity: a jump from one branch to another implies some degree of strictness. A special case of this is that the fixpoints of strict functions are bottom.

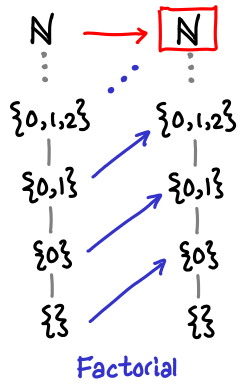

The tour de force example of fixpoints is the “Hello world” of recursive functions: factorial. Unlike our previous examples, the domain here is infinite, so fix needs to apply f “infinitely” many times to get the true factorial. Fortunately, any given call to calculuate the factorial n! will only need n applications. Recall that the fixpoint style definition of factorial is as follows:

factorial = fix (\f n -> if n == 0 then 1 else n * f (n - 1))

Here is how the domain of the factorial function grows with successive applications:

The reader is encouraged to verify this is the case. Next time, we’ll look at this example not on the flat domain of natural numbers, but the vertical domain of natural numbers, which will nicely tie to together a lot of the material we’ve covered so far.

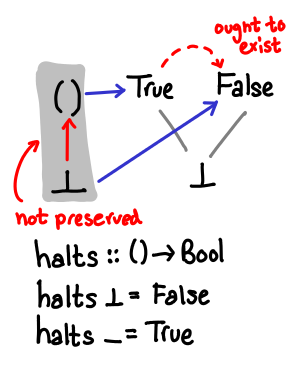

December 10, 2010Between packing and hacking on GHC, I didn’t have enough time to cough up the next post of the series or edit the pictures for the previous post, so all you get today is a small errata post.

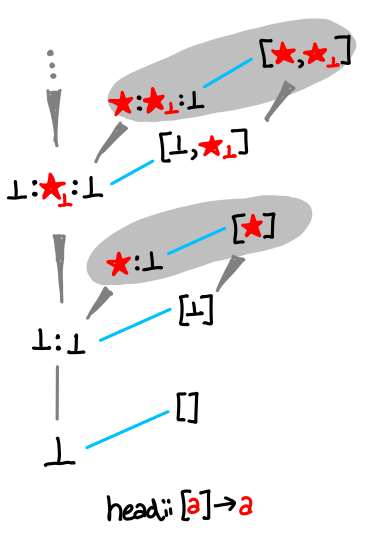

- The full list diagram is missing some orderings: ★:⊥ ≤ ★:⊥:⊥ and so on.

- In usual denotational semantics, you can’t distinguish between ⊥ and

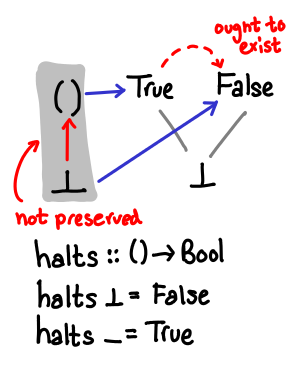

λ_.⊥. However, as Anders Kaseorg and the Haskell Report point out, with seq you can distinguish them. This is perhaps the true reason why seq is a kind of nasty function. I’ve been assuming the stronger guarantee (which is what zygoloid pointed out) when it’s not actually true for Haskell. - The “ought to exist” arrow in the halts diagram goes the wrong direction.

- In the same fashion of the full list diagram,

head is missing some orderings, so in fact they gray blob is entirely connected. There are situations when we can have disconnected blobs, but not for a domain with only one maximum. - Obvious typo for fst.

- The formal partial order on functions was not defined correctly: it originally stated that for f ≤ g, f(x) = g(x); actually, it’s weaker than that: f(x) ≤ g(x).

- A non-erratum: the right-side of the head diagram is omitted because… adding all the arrows makes it look pretty ugly. Here is the sketch I did before I decided it wasn’t a good picture.

Thanks Anders Kaseorg, zygoloid, polux, and whoever pointed out the mistake in the partial order on functions (can’t find that correspondence now) for corrections.

Non sequitur. Here is a really simple polyvariadic function. The same basic idea is how Text.Printf works. May it help you in your multivariadic travels. :

{-# LANGUAGE FlexibleInstances #-}

class PolyDisj t where

disj :: Bool -> t

instance PolyDisj Bool where

disj x = x

instance PolyDisj t => PolyDisj (Bool -> t) where

disj x y = disj (x || y)

December 8, 2010Gin, because you’ll need it by the time you’re done reading this.

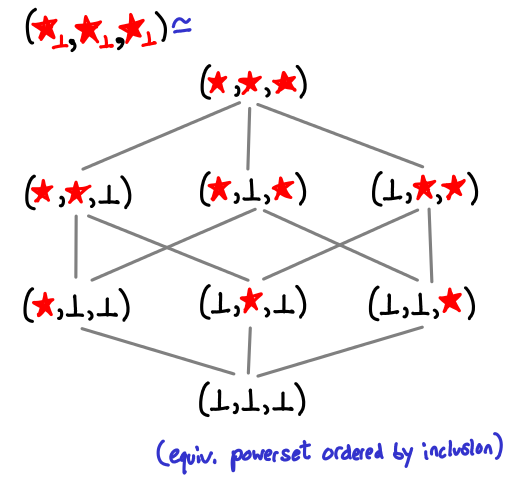

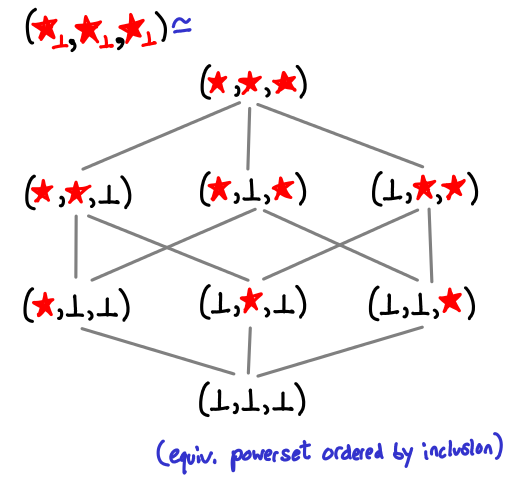

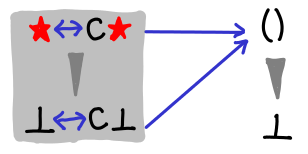

Last time we looked the partial orders of values for data types. There are two extra things I would like to add: an illustration of how star-subscript-bottom expands and an illustration of list without using the star-subscript-bottom notation.

Here is a triple of star-subscript-bottoms expanded, resulting in the familiar Hasse diagram of the powerset of a set of three elements ordered by inclusion:

And here is the partial order of lists in its full exponential glory (to fit it all, the partial order of the grey spine increases as it goes to the right.)

Now, to today’s subject, functions! We’ve only discussed data types up until now. In this post we look a little more closely at the partial order that functions have. We’ll introduce the notion of monotonicity. And there will be lots of pictures.

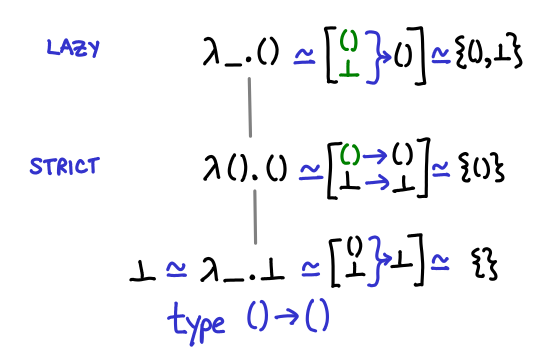

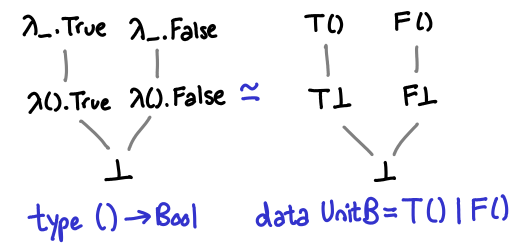

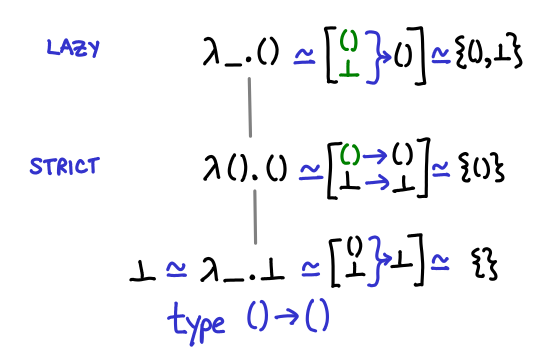

Let’s start with a trivial example: the function of unit to unit, () -> (). Before you look at the diagram, how many different implementations of this function do you think we can write?

Three, as it turns out. One which returns bottom no matter what we pass it, one which is the identity function (returns unit if it is passed unit, and bottom if it is passed bottom), and one which is const (), that is, returns unit no matter what it is passed. Notice the direct correspondence between these different functions and strict and lazy evaluation of their argument. (You could call the bottom function partial, because it’s not defined for any arguments, although there’s no way to directly write this and if you just use undefined GHC won’t emit a partial function warning.)

In the diagram I’ve presented three equivalent ways of thinking about the partial order. The first is just terms in the lambda calculus: if you prefer Haskell’s notation you can translate λx.x into \x -> x. The second is a mapping of input values to output values, with bottom explicitly treated (this notation is good for seeing bottom explicitly, but not so good for figuring out what values are legal—that is, computable). The third is merely the domains of the functions: you can see that the domains are steadily getting larger and larger, from nothing to the entire input type.

At this point, a little formality is useful. We can define a partial order on a function as follows: f ≤ g if and only if dom(f) (the domain of f, e.g. all values that don’t result in f returning bottom) ⊆ dom(g) and for all x ∈ dom(f), f(x) ≤ g(x). You should verify that the diagram above agrees (the second condition is pretty easy because the only possible value of the function is ()).

A keen reader may have noticed that I’ve omitted some possible functions. In particular, the third diagram doesn’t contain all possible permutations of the domain: what about the set containing just bottom? As it turns out, such a function is uncomputable (how might we solve the halting problem if we had a function () -> () that returned () if its first argument was bottom and returned bottom if its first argument was ()). We will return to this later.

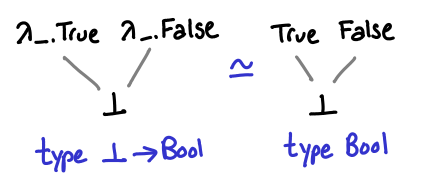

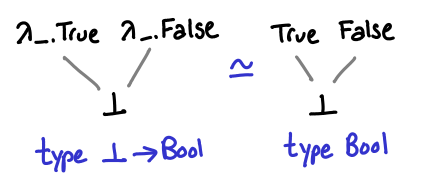

Since () -> () has three possible values, one question to ask is whether or not there is a simpler function type that has fewer values? If we admit the empty type, also written as ⊥, we can see that a -> ⊥ has only one possible value: ⊥.

Functions of type ⊥ -> a also have some interesting properties: they are isomorphic to plain values of type a.

In the absence of common subexpression elimination, this can be a useful way to prevent sharing of the results of lazy computation. However, writing f undefined is annoying, so one might see a () -> a instead, which has not quite the same but similar semantics.

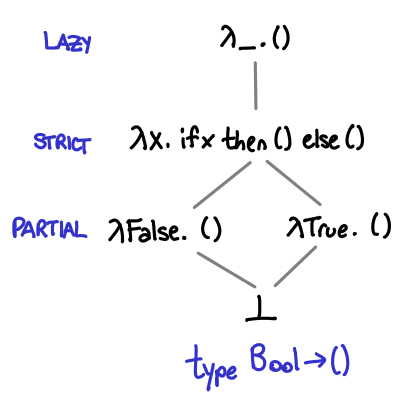

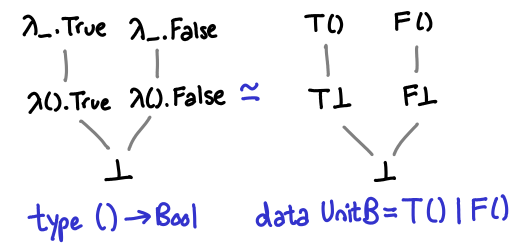

Up until this point, we’ve considered only functions that take ⊥ or () as an argument, which are not very interesting. So we can consider the next possible simplest function: Bool -> (). Despite the seeming simplicity of this type, there are actually five different possible functions that have this type.

To see why this might be the case, we might look at how the function behaves for each of its three possible arguments:

or what the domain of each function is:

These partial orders are complete, despite the fact there seem to be other possible permutations of elements in the domain. Once again, this is because we’ve excluded noncomputable functions. We will look at this next.

Consider the following function, halts. It returns True if the computation passed to it eventually terminates, and False if it doesn’t. As we’ve seen by fix id, we can think of bottom as a nonterminating computation. We can diagram this by drawing the Hasse diagrams of the input and output types, and then drawing arrows mapping values from one diagram to the other. I’ve also shaded with a grey background values that don’t map to bottom.

It is widely known that the halting problem is uncomputable. So what is off with this perfectly plausible looking diagram?

The answer is that our ordering has not been preserved by the function. In the first domain, ⊥ ≤ (). However, the resulting values do not have this inequality: False ≰ True. We can sum this condition as monotonicity, that is, f is monotonic when if x ≤ y then f(x) ≤ f(y).

Two degenerate cases are worth noting here:

- In the case where f(⊥) = ⊥, i.e. the function is strict, you never have to worry about ⊥ not being less than any other value, as by definition ⊥ is less than all values. In this sense making a function strict is the “safe thing to do.”

- In the case where f(x) = c (i.e. a constant function) for all x, you are similarly safe, since any ordering that was in the original domain is in the new domain, as c ≤ c. Thus, constant functions are an easy way of assigning a non-bottom value to f(⊥). This also makes clear that the monotonicity implication is only one direction.

What is even more interesting (and somewhat un-obvious) is that we can write functions that are computable, are not constant, and yet give a non-⊥ value when passed ⊥! But before we get to this fun, let’s first consider some computable functions, and verify monotonicity holds.

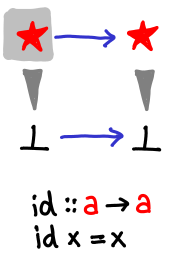

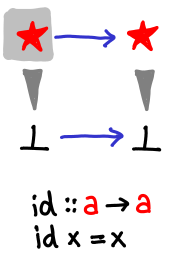

Simplest of all functions is the identity function:

It does so little that it is hardly worth a mention, but you should verify that you’re following along with the notation.

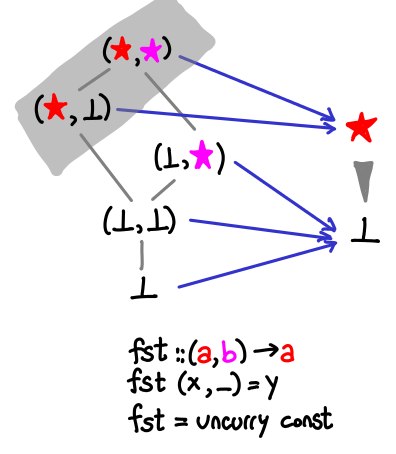

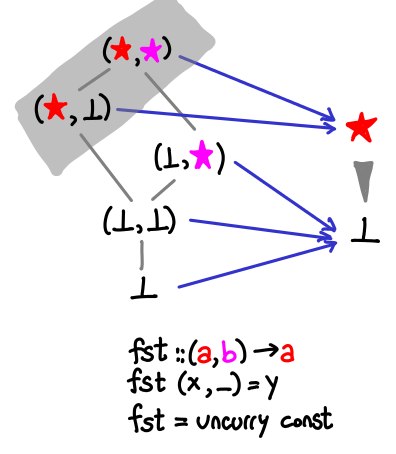

A little less trivial is the fst function, which returns the first element of a pair.

Look and verify that all of the partial ordering is preserved by the function: since there is only one non-bottom output value, all we need to do is verify the grey is “on top of” everything else. Note also that our function doesn’t care if the snd value of the pair is bottom.

The diagram notes that fst is merely an uncurried const, so let’s look at that next.

We would like to consider the sense of const as a -> (b -> a), a function that takes a value and returns a function. For the reader’s benefit we’ve also drawn the Hasse diagrams of the resulting functions. If we had fixed the type of a or b, there would be more functions in our partial order, but without this, by parametricity there is very little our functions can do.

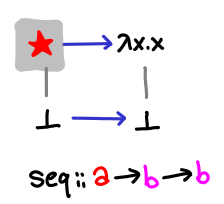

It’s useful to consider const in contrast to seq, which is something of a little nasty function, though it can be drawn nicely with our notation.

The reason why the function is so nasty is because it works for any type (it would be a perfectly permissible and automatically derivable typeclass): it’s able to see into any type a and see that it is either bottom or one of its constructors.

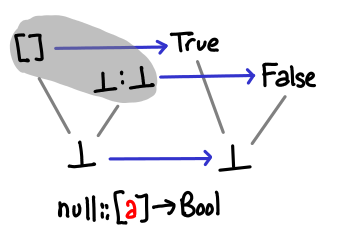

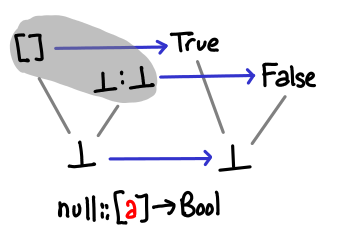

Let’s look at some functions on lists, which can interact in nontrivial ways with bottom. null has a very simple correspondence, since what it is really asking is “is this the cons constructor or the null constructor?”

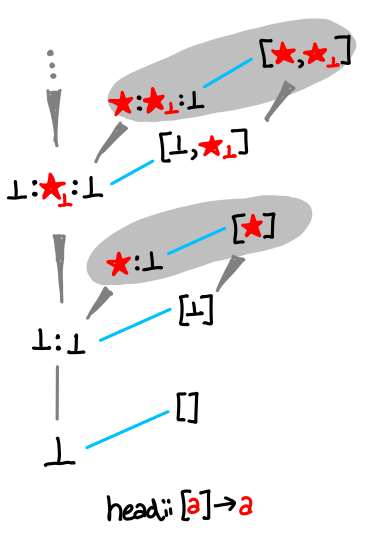

head looks a little more interesting.

There are multiple regions of gray, but monotonicity is never violated: despite the spine which expands infinitely upwards, each leaf contains a maximum of the partial order.

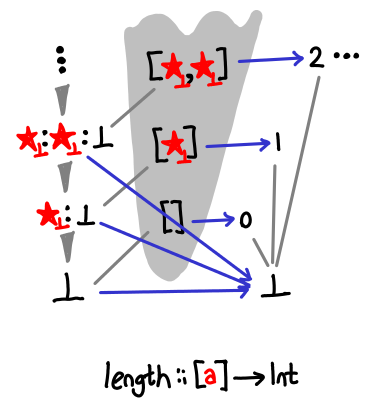

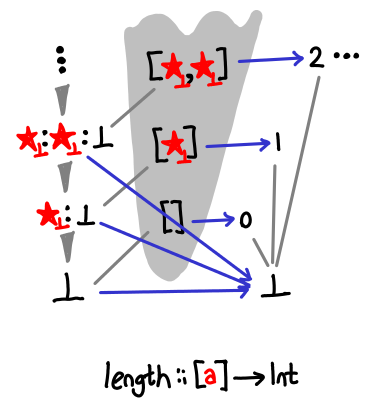

There is a similar pattern about length, but the leaves are arranged a little differently:

Whereas head only cares about the first value of the list not being bottom, length cares about the cdr of the cons cell being null.

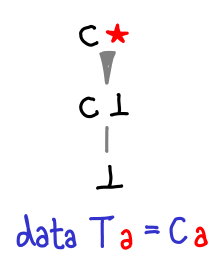

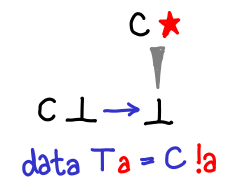

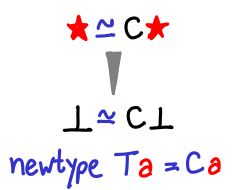

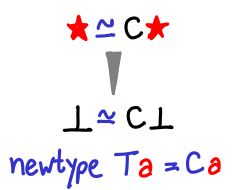

We can also use this notation to look at data constructors and newtypes.

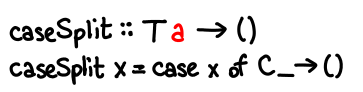

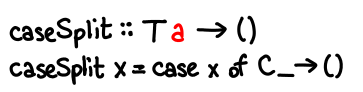

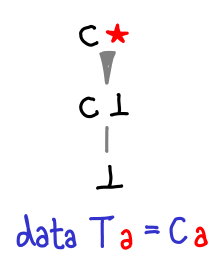

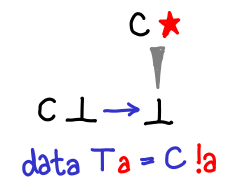

Consider the following function, caseSplit, on an unknown data type with only one field.

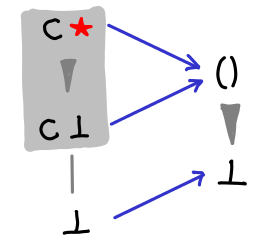

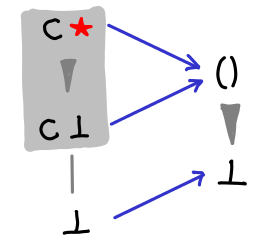

We have the non-strict constructor:

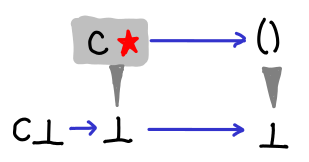

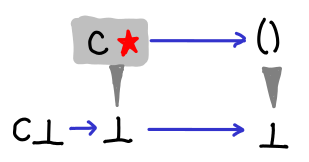

The strict constructor:

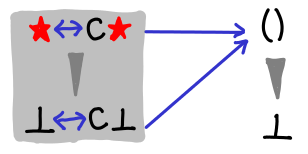

And finally the newtype:

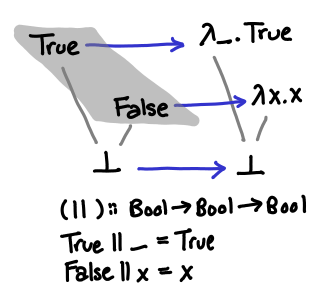

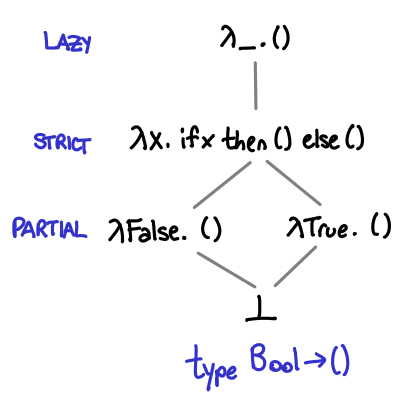

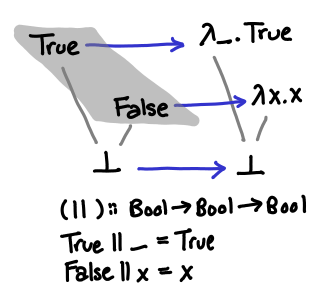

We are now ready for the tour de force example, a study of the partial order of functions from Bool -> Bool, and a consideration of the boolean function ||. To refresh your memory, || is usually implemented in this manner:

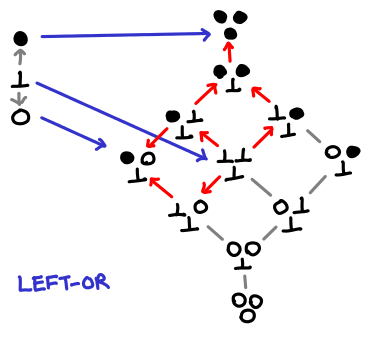

Something that’s not too obvious from this diagram (and which we would like to make obvious soon) is the fact that this operator is left-to-right: True || ⊥ = True, but ⊥ || True = ⊥ (in imperative parlance, it short-circuits). We’ll develop a partial order that will let us explain the difference between this left-or, as well as its cousin right-or and the more exotic parallel-or.

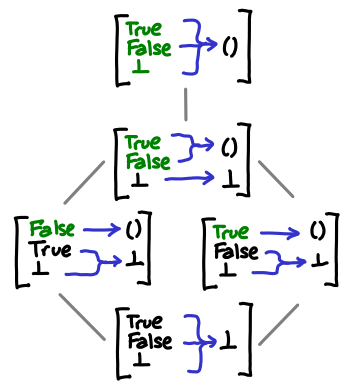

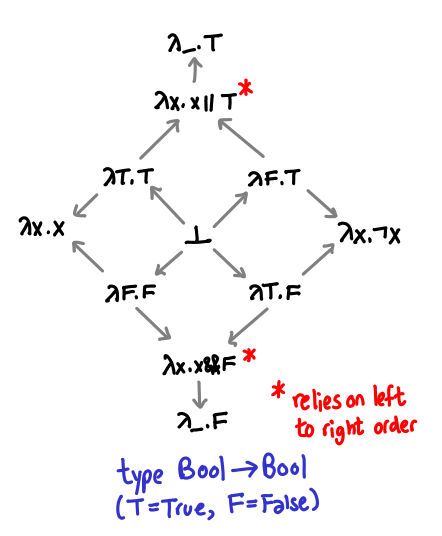

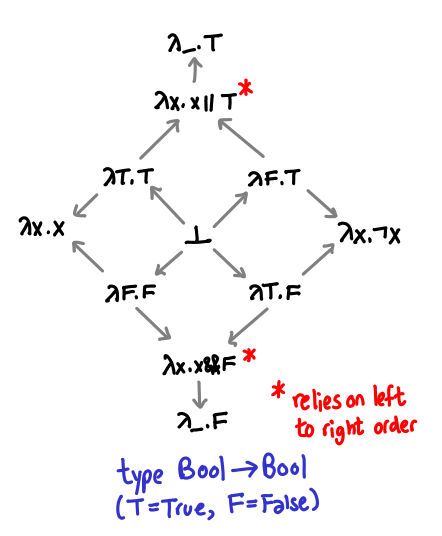

Recall that || is curried: its type is Bool -> (Bool -> Bool). We’ve drawn the partial order of Bool previously, so what is the complete partial order of Bool -> Bool? A quite interesting structure!

I’ve violated my previously stated convention that more defined types are above other types, in order to demonstrate the symmetry of this partial order. I’ve also abbreviated True as T and False as F. (As penance, I’ve explicitly drawn in all the arrows. I will elide them in future diagrams when they’re not interesting.)

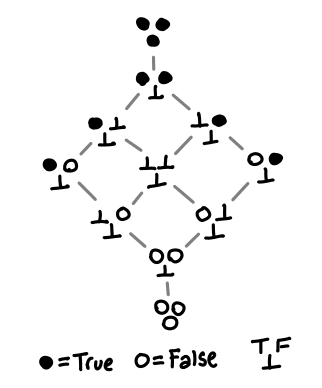

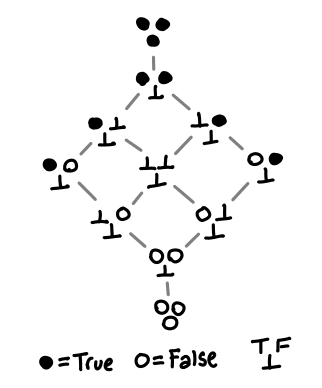

These explicit lambda terms somewhat obscure what each function actually does, so here is a shorthand representation:

Each triple of balls or bottom indicates how the function reacts to True, False and bottom.

Notice the slight asymmetry between the top/bottom and the left/right: if our function is able to distinguish between True and False, there is no non-strict computable function. Exercise: draw the Hasse diagrams and convince yourself of this fact.

We will use this shorthand notation from now on; refer back to the original diagram if you find yourself confused.

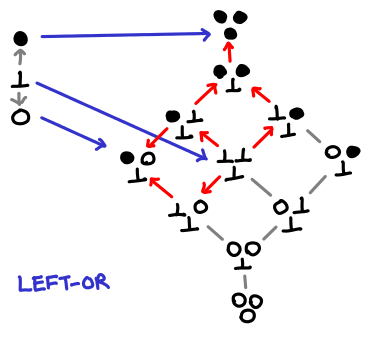

The first order (cough) of business is to redraw the Hasse-to-Hasse diagram of left-or with the full partial order.

Verify that using transitivity we can recover the simplified, partial picture of the partial order. The red arrows indicate the preserved ordering from the original boolean ordering.

The million dollar question is this: can we write a different mapping that preserves the ordering (i.e. is monotonic). As you might have guessed, the answer is yes! As an exercise, draw the diagram for strict-or, which is strict in both its arguments.

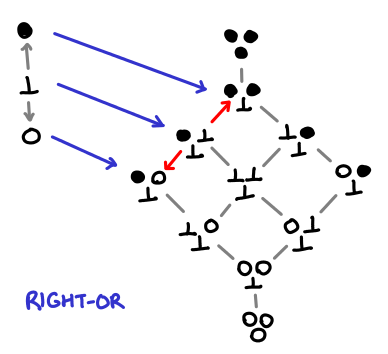

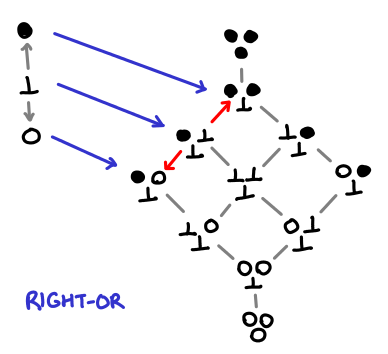

Here is the diagram of right-or:

Notice something really interesting has happened: bottom no longer maps to bottom, but we’ve still managed to preserve the ordering. This is because the target domain has a rich enough structure to allow us to do this! If this seems a little magical to you, consider how we might write a right-or in Haskell:

rightOr x = \y -> if y then True else x

We just don’t look at x until we’ve looked at y; in our diagram, it looks as if x has been slotted into the result if y is False.

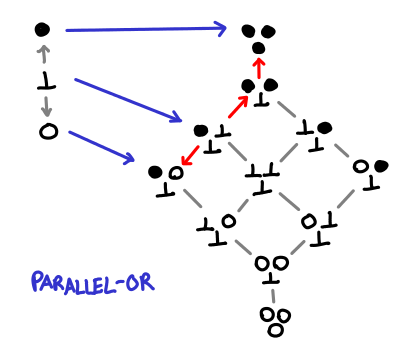

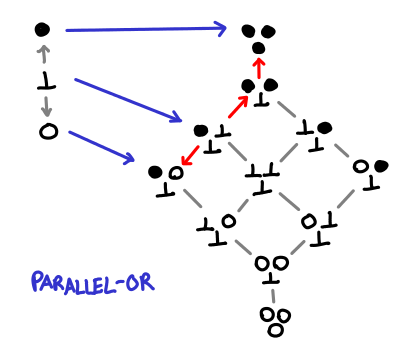

There is one more thing we can do (that has probably occurred to you by now), giving us maximum ability to give good answers in the face of bottom, parallel-or:

Truly this is the farthest we can go: we can’t push our functions any further down the definedness chain and we can’t move our bottom without changing the strict semantics of our function. It’s also not obvious how one would implement this in Haskell: it seems we really need to be able to pattern match against the first argument in order to decide whether or not to return const True. But the function definitely is computable, since monotonicity has not been violated.

The name is terribly suggestive of the correct strategy: evaluate both arguments in parallel, and return True if any one of them returns True. In this way, the Hasse diagram is quite misleading: we never actually return three distinct functions. However, I’m not really sure how to illustrate this parallel approach properly.

This entire exercise has a nice parallel to Karnaugh maps and metastability in circuits. In electrical engineering, you not only have to worry about whether or not a line is 1 or 0, but also whether or not it is transitioning from one to the other. Depending on how you construct a circuit, this transition may result in a hazard even if the begin and end states are the same (strict function), or it may stay stable no matter what the second line dones (lazy function). I encourage an electrical engineer to comment on what strict-or, left-or, right-or and parallel-or (which is what I presume is usually implemented) look like at the transistor level. Parallels like these make me feel that my time spent learning electrical engineering was not wasted. :-)

That’s it for today. Next time, we’ll extend our understanding of functions and look at continuity and fixpoints.

Postscript. There is some errata for this post.

December 6, 2010Values of Haskell types form a partial order. We can illustrate this partial order using what is called a Hasse diagram. These diagrams are quite good for forcing yourself to explicitly see the bottoms lurking in every type. Since my last post about denotational semantics failed to elicit much of a response at all, I decided that I would have better luck with some more pictures. After all, everyone loves pictures!

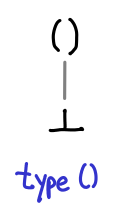

We’ll start off with something simple: () or unit.

Immediately there are a few interesting things to notice. While we normally think of unit as only having one possible value, (), but in fact they have two: () and bottom (frequently written as undefined in Haskell, but fix id will do just as well.) We’ve omitted the arrows from the lines connecting our partial order, so take as a convention that higher up values are “greater than” their lower counterparts.

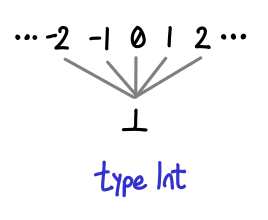

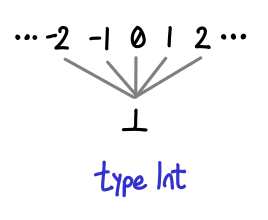

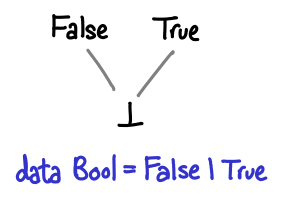

A few more of our types work similarly, for example, Int and Bool look quite similar:

Note that Int without bottom has a total ordering independent of our formulation (the usual -3 is less than 5 affair, alluded to by the Ord instance for Int). However, this is not the ordering you’re looking for! In particular, it doesn’t work if bottom is the game: is two less than or greater than bottom? In this partial ordering, it is “greater”.

It is no coincidence that these diagrams look similar: their unlifted sets (that is, the types with bottom excluded) are discrete partial orders: no element is less than or greater than another.

What happens if we introduce data types that include other data types? Here is one for the natural numbers, Peano style (a natural number is either zero or the successor of a natural number.)

We no longer have a flat diagram! If we were in a strict language, this would have collapsed back into the boring partial orders we had before, but because Haskell is lazy, inside every successor constructor is a thunk for a natural number, which could be any number of exciting things (bottom, zero, or another successor constructor.)

We’ll see a structure that looks like this again when we look at lists.

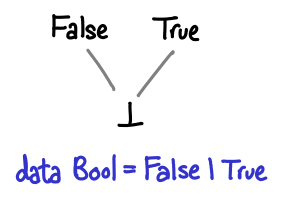

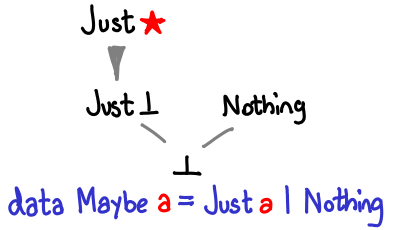

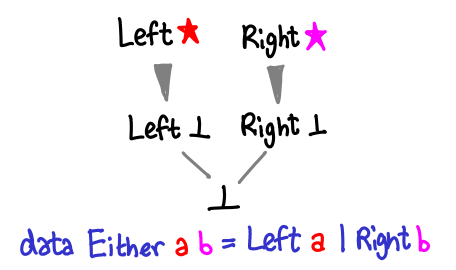

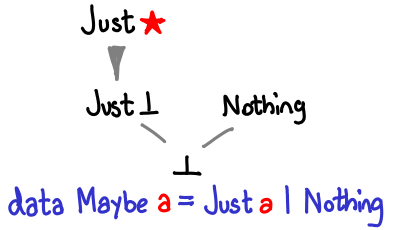

I’d like to discuss polymorphic data types now. In Haskell Denotational semantics wikibook, in order to illustrate these data types, they have to explicitly instantiate all of the types. We’ll adopt the following shorthand: where I need to show a value of some polymorphic type, I’ll draw a star instead. Furthermore, I’ll draw wedges to these values, suggestive of the fact that there may be more than one constructor for that type (as was the case for Int, Bool and Nat). At the end of this section I’ll show you how to fill in the type variables.

Here is Maybe:

If Haskell allowed us to construct infinite types, we could recover Nat by defining Maybe (Maybe (Maybe …)).

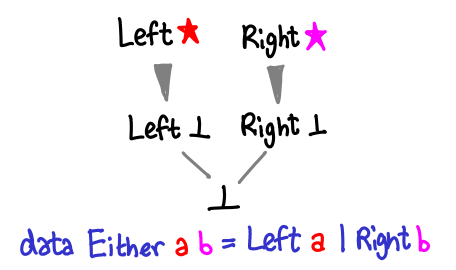

Either looks quite similar, but instead of Nothing we have Right:

Is Left ⊥ greater than or less than Right () in this partial order? It’s a trick question: since they are different constructors they’re not comparable anymore.

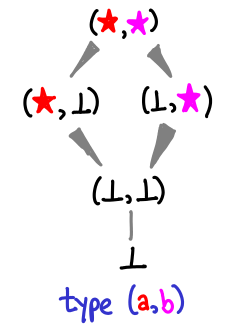

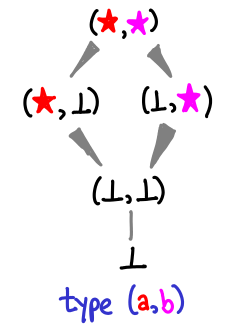

Here’s a more interesting diagram for a 2-tuple:

The values merge back at the very top! This is because while ((), ⊥) is incomparable to (⊥, ()), both of them are less than ((), ()) (just imagine filling in () where the ⊥ is in both cases.)

If we admit lazy data structures, we get a lot richer space of possible values than if we’re forced to use strict data structures. If these constructors were strict, our Hasse diagrams would still be looking like the first few. In fact, we can see this explicitly in the difference between a lazy constructor and a strict constructor:

The strict constructor squashes ⊥ and C ⊥ to be the same thing.

It may also be useful to look at newtype, which merely constructs an isomorphism between two types:

It looks a bit like the strict constructor, but it’s actually not at all the same. More on this in the next blog post.

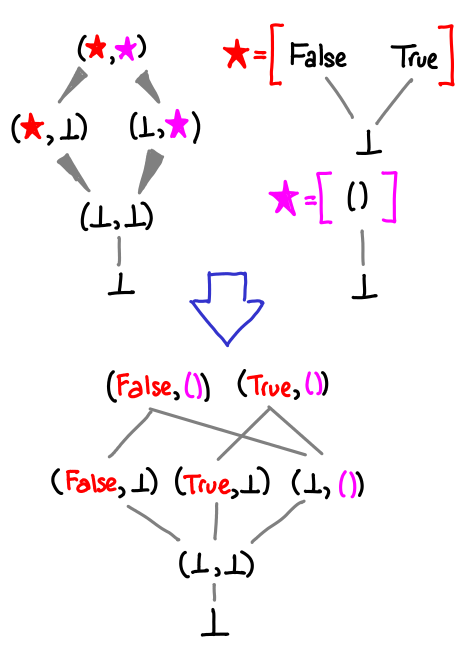

How do we expand stars? Here’s a diagram showing how:

Graft in the diagram for the star type (excluding bottom, since we’ve already drawn that into the diagram), and duplicate any of the incoming and outgoing arrows as necessary (thus the wedge.) This can result in an exponential explosion in the number of possible values, which is why I’ll prefer the star notation.

And now, the tour de force, lazy lists:

Update. There’s one bit of extra notation: the stars with subscript ⊥ mean that you’ll need to graft in bottom as well (thanks Anonymous for pointing this out.) Tomorrow we’ll see list expanded in its full, exponential glory.

We almost recover Nat if we set a to be (), but they’re not quite isomorphic: every () might actually be a bottom, so while [()] and [⊥] are equivalent to one, they are different. In fact, we actually want to set a to the empty type. Then we would write 5 as [⊥, ⊥, ⊥, ⊥, ⊥].

Next time, we’ll draw pictures of the partial ordering of functions and illustrate monotonicity.

December 3, 2010I’ve had the pleasure of attending a number of really interesting talks over the past few months, so many that I couldn’t find time to write thorough articles for each of them as I did over the summer. So you’ll have to forgive me for putting two of them in compressed form here. There is something of a common theme of recasting a problem on a different input domain in order to achieve results, as I hope will become evident by these summaries.

A Language for Mathematics by Mohan Ganesalingam. Big idea: Apply linguistics and natural language processing techniques to mathematical language—the type found in textbooks and proofs.

Ganesalingam has big goals: his long term project is to “enable computers to do mathematics in the same way that humans do.” “But wait,” you may say, “aren’t we already approaching this with proof assistants?” Unfortunately, the answer to this is no: proof assistants are quite good at capturing rigorous formal reasoning, but are terrible at actually capturing the soft ideas that mathematicians gesture at when writing proofs and textbooks. The first step in this program is understanding this mathematical language—thus, the title of his talk.

Why do we have any reason to believe that this program will be any more successful than current research in linguistics and NLP? After all, most papers and textbooks use English interspersed with mathematical notation, and grand ideas about semantic analysis have given way to more effective but theoretically less appealing statistical methods. Ganesalingam makes some key observations here: in essence, mathematical language has the right dose of formality to make traditionally hard problems tractable. Only a small lexicon is necessary, and then mathematical terms can be defined in terms of other mathematical terms, and in many cases, there is a clear semantics for a mathematical statement: we can in principle translate it into a statement in higher order logic.

Further reading: Slides for a similar presentation that was given at Stanford, an informal non-technical introduction, author’s homepage.

Evaluating Formulas on Graphs by Anuj Dawar. There are really two big ideas here. Big idea 1. Generalize graph problems into the question “does this first-order logical formula hold on this graph?”, treating your algorithm as a function on two inputs: the graph and the logical formula. Big idea 2. Use graph structure theory to characterize what input spaces of graphs we can efficiently solve these FO formulas for.

First big idea: the study of graph problems is frequently focused on an individual graph problem at a time: after all, being able to assume a concrete problem instance makes it easier to reason about things. What Dawar’s talk introduces is a way to talk about large classes of graph problems by bundling them up into logics (of various shapes and sizes.) Existential second-order logic gives you all NP problems (Fagin); first-order logic is more restrictive but admits better analysis. Separating out the formula from your problem also lets you apply parametrized complexity theory: the formula is an input to your algorithm, and you set it constant or vary it. Unfortunately, the problem (even for fixed graphs) is still PSPACE-complete, so we need another way to get a grip on the problem.

Second big idea: restrict the input graphs in order to make the algorithms tractable. This involves a bit of graph theory knowledge which I’m not going to attempt to summarize, but there are some really nice results in this area:

- Seese (1996): For the class of graphs with degree bounded by k, every FO definable property is decidable in linear time.

- Frick and Grohe (2001): For the class of graphs of local tree-width bounded by a function f, every FO definable property is decidable in quadratic time.

- Flum and Grohe (2001): For the class of graphs excluding K_k as a minor, every FO definable property is decidable in O(n^5).

One oddball fact is that Flum and Grohe’s O(n^5) bound on complexity has a constant factor which may not be computable.

By the end, we get to the edge of research: he introduces a new class of graphs, nowhere dense graphs, motivates why we have good reason to think this characterizes tractability, and says that they hope to establish FO is fixed parameter tractable.

A quick aside: one of the things I really enjoy about well-written theoretical research talks is that they often introduce me to subfields of computer science that I would not have otherwise encountered. This presentation was a whirlwind introduction to graph theory and parametrized complexity theory, both topics I probably would not have otherwise considered interesting, but afterwards I had tasted enough of to want to investigate further. I think it is quite commendable for a researcher doing highly abstract work to also be giving seminars working up the background knowledge necessary to understand their results.

Further reading: Full course on these topics

December 1, 2010An extended analogy on the denotational and game semantics of ⊥

This is an attempt at improving on the Haskell Wikibooks article on Denotational Semantics by means of a Dr. Strangelove inspired analogy.

The analogy. In order to prevent Brigadier General Jack D. Ripper from initiating a nuclear attack on Russia, the Pentagon decides that it will be best if every nuclear weapon requires two separate keys in order to be activated, both of which should not be known by the same person at the same time under normal circumstances. Alice is given one half of the key, Bob the other half. If Ripper asks Alice for her half of the key, she can tell him her key, A. However, asking Alice for Bob’s key won’t work, since she doesn’t know what Bob’s key is.

Suppose Ripper asked Alice anyway, and she told him “I don’t know Bob’s key.” In this case, Ripper now have a concrete piece of information: Alice does not have Bob’s key. He can now act accordingly and ask Bob for the second key. But suppose that, instead of telling him outright that she didn’t know the key, she told him, “I can tell you, but can you wait a little bit?” Ripper decides to wait—he’d probably have a time convincing Bob to hand over the key. But Alice never tells Ripper the key, and he keeps waiting. Even if Ripper decides to eventually give up waiting for Alice, it’s a lot harder for him to strategize when Alice claims she has the key but never coughs it up.

Alice, curious what would happen if she tried to detonate the nuclear bomb, sets off to talk to Larry who is responsible for keying in the codes. She tells the technician, “I have Alice’s key and I have Bob’s key.” (We, of course, know that she doesn’t actually have Bob’s key.) Larry is feeling lazy, and so before asking Alice for the keys, he phones up the Pentagon and asks if nuclear detonation is permitted. It is not, and he politely tells Alice so. Unruffled, Alice goes off and finds Steve, who can also key in the codes. She tells Steve that she has Alice’s key and Bob’s key. Steve, eager to please, asks Alice, “Cool, please tell me your key and Bob’s key.” Alice hands over her key, but stops on Bob’s key, and the conversation never finishes.

Nevertheless, despite our best efforts, Ripper manages to get both keys anyway and the world is destroyed in nuclear Armageddon anyway. ☢

Notation. Because this key is in two parts, it can be represented as a tuple. The full key that Ripper knows is (A, B), what Alice knows about the full key is (A, ⊥), and what Bob knows is (⊥, B). If I am (clueless) civilian Charlie, my knowledge might be (⊥, ⊥). We can intuitively view ⊥ as a placeholder for whenever something is not known. (For simplicity, the types of A and B are just unit.)

I know more than you. We can form a partial ordering of who knows more than who. Ripper, with the full key, knows more than Alice, Bob or Charlie. Alice knows more than Charlie, and Bob knows more than Charlie. We can’t really say that Alice knows more than Bob, or vice versa, since they know different pieces of data. ⊥ is at the bottom of this ordering because, well, it represents the least possible information you could have.

The difference between nothing and bottom. Things play out a bit differently when Alice says “I don’t know” versus when Alice endlessly delays providing an answer. This is because the former case is not bottom at all! We can see this because Alice actually says something in the first case. This something, though it is not the key, is information, specifically the Nothing constructor from Maybe. It would be much more truthful to represent Alice’s knowledge as (Just A, Nothing) in this case. In the second case, at any point Alice could give a real answer, but she doesn’t.

A strange game. The only winning move is not to play. There is a lot of emphasis on people asking other people for pieces of information, and those people either responding or endlessly delaying. In fact, this corresponds directly to the notion of bottom from game semantics. When Ripper asks Alice for information about her key, we can write out the conversation as the sequence: “tell me the first value of the tuple”, “the value is A”, “tell me the second value of the tuple”, “…” Alice is speechless at the last question, because in game semantics parlance, she doesn’t have a strategy (the knowledge) for answering the question “tell me the second value of the tuple.” Clueless Charlie is even worse off, having no strategy for either question: the only time he is happy is if no one asks him any questions at all. He has the empty strategy.

Don’t ask, don’t tell. Consider function application. We might conceptualize this as “Here is the value A, here is the value B, please tell me if I can detonate the nuclear device.” This is equivalent to Steve’s strict evaluation. But we don’t have to setup the conversation this way: the conversation with Larry started off with, “I have the first key and I have the second key. Please tell me if I can detonate the nuclear device.” Larry might then ask Alice, “Ok, what is the first key?”—in particular, this will occur if Larry decides to do a case statement on the first key—but if Larry decides he doesn’t need to ask Alice for any more information, he won’t. This will make Charlie very happy, since he is only happy if he is not asked any questions at all.

Ask several people at the same time. In real life, if someone doesn’t give us an answer after some period of time, we can decide to stop listening and go do something else. Can programs do this too? It depends on what language you’re in. In Haskell, we can do this with nondeterminism in the IO monad (or push it into pure code with some caveats, as unamb does.)

What’s not in the analogy. Functions are data too: and they can be partially defined, e.g. partial functions. The fixpoint operator can be thought to use less defined versions of a function to make more defined versions. This is very cool, but I couldn’t think of an oblique way of presenting it. Omitted are the formal definitions from denotational semantics and game semantics; in particular, domains and continuous functions are not explained (probably the most important pieces to know, which can be obscured by the mathematical machinery that usually needs to get set up before defining them).

Further reading. If you think I’ve helped you’ve understand bottom, go double check your understanding of the examples for newtype, perhaps one of the subtlest cases where thinking explicitly about bottom and about the conversations the functions, data constructors and undefineds (bottoms) are having. The strictness annotation means that the conversation with the data constructor goes something like “I have the first argument, tell me what the value is.” “Ok, what is the first argument?” These notes on game semantics (PDF) are quite good although they do assume familiarity with denotational semantics. Finding the formal definitions for these terms and seeing if they fit your intuition is a good exercise.