February 14, 2011Guys, I have a secret to admit: I’m terrified of binomials. When I was in high school, I had a traumatic experience with Donald Knuth’s The Art of Computer Programming: yeah, that book that everyone recommends but no one has actually read. (That’s not actually true, but that subject is the topic for another blog post.) I wasn’t able to solve any recommended exercises in the mathematical first chapter nor was I well versed enough in computers to figure out what assembly languages were about. But probably the most traumatizing bit was Knuth’s extremely compact treatment of the mathematical identities in the first chapter we were expected memorize. As I would find out later in my mathematical career, it pays to convince yourself that a given statement is true before diving into the mess of algebraic manipulation in order to actually prove it.

One of my favorite ways of convincing myself is visualization. Heck, it’s even a useful way of memorizing identities, especially when the involve multiple parameters as binomial coefficients do. If I ever needed to calculate a binomial coefficient, I’d be more likely to bust out Pascal’s triangle than use the original equation.

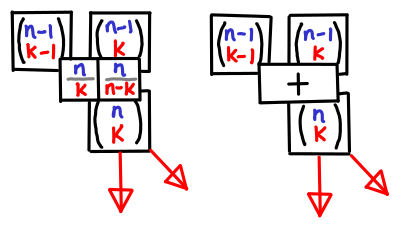

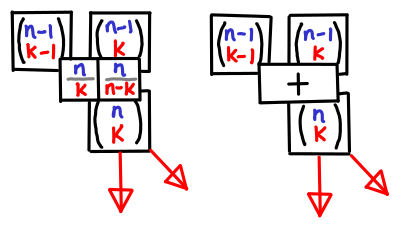

Of course, at some point you have to write mathematical notation, and when you need to do that, reliance on the symmetric rendition of Pascal’s triangle (pictured on the right) can be harmful. Without peeking, the addition rule is obvious in Pascal’s triangle, but what’s the correct mathematical formulation?

[latex size=2]{n \choose k} = {n-1 \choose k} + {n-1 \choose k+1}[/latex]

[latex size=2]{n \choose k} = {n-1 \choose k-1} + {n-1 \choose k}[/latex]

I hate memorizing details like this, because I know I’ll get it wrong sooner or later if I’m not using the fact regularly (and while binomials are indubitably useful to the computer scientist, I can’t say I use them frequently.)

Pictures, however. I can remember pictures.

And if you visualize Pascal’s triangle as an actual table wih n on the y-axis and k on the x-axis, knowing where the spatial relationship of the boxes means you also know what the indexes are. It is a bit like visualizing dynamic programming. You can also more easily see the symmetry between a pair of equations like:

[latex size=2]{n \choose k} = {n \over k}{n-1 \choose k-1}[/latex]

[latex size=2]{n \choose k} = {n \over n-k}{n-1 \choose k}[/latex]

which are presented by the boxes on the left.

Of course, I’m not the first one to think of these visual aids. The “hockey stick identities” for summation down the diagonals of the traditional Pascal’s triangle are quite well known. I don’t think I’ve seen them pictured in tabular form, however. (I’ve also added row sums for completeness.)

Symmetry is nice, but unfortunately our notation is not symmetric, and so for me, remembering the hockey stick identities this ways saves me the trouble from then having to figure out what the indexes are. Though I must admit, I’m curious if my readership feels the same way.

February 11, 2011OpenIntents has a nifty application called SensorSimulator which allows you feed an Android application accelerometer, orientation and temperature sensor data. Unfortunately, it doesn’t work well on the newer Android 2.x series of devices. In particular:

- The mocked API presented to the user is different from the true API. This is due in part to the copies of the Sensor, SensorEvent and SensorEventHandler that the original code had in order to work around the fact that Android doesn’t have public constructors for these classes,

- Though the documentation claims “Whenever you are not connected to the simulator, you will get real device sensor data”, this is not actually the case: all of the code that interfaces with the real sensor system is commented out. So not only is are the APIs incompatible, you have to edit your code from one way to another when you want to vary testing. (The code also does a terrible job of handling the edge condition where you are not actually testing the application.)

Being rather displeased with this state of affairs, I decided to fix things up. With the power of Java reflection (cough cough) I switched the representation over to the true Android objects (effectively eliminating all overhead when the simulator is not connected.) Fortunately, Sensor and SensorEvent are small, data-oriented classes, so I don’t think I stepped on the internal representation too much, though the code will probably break horribly with future versions of the Android SDK. Perhaps I should suggest to upstream that they should make their constructors public.

You can grab the code here: SensorSimulator on Github. Let me know if you find bugs; I’ve only tested on Froyo (Android 2.2).

February 9, 2011To: John Wellesz

First off, I’d like to thank you for authoring the php.vim indentation plugin. Recent experiences with some other indentation plugins made me realize how annoying editing can be without a good indentation plugin, and php.vim mostly has served me well over the years.

However, I do have a suggestion for the default behavior of PHP_autoformatcomment. When this option is enabled (as it is by default), it sets the ‘w’ format option, which performs paragraphing based off of trailing newlines. Unfortunately, this option has a number of adverse effects that may not be obvious unless you are paying attention to trailing newlines:

When you are typing a comment, and you get an automatic linewrap, Vim will leave behind a single trailing whitespace to indicate “this is not the end of the paragraph!”

If you select a few adjacent comments, like such:

// Do this, but if you do that then

// be sure to frob the wibble

and then type ‘gq’, expecting it to be rewrapped, nothing will happen. This is because these lines lack trailing whitespace, so Vim thinks they are each a seperate sentence.

I also believe that ‘comments’ option should be unconditionally set by the indent plugin, as you load the ‘html’ plugin which clobbers any pre-existing value (specified, for example, by a .vim/indent/php.vim file).

Please let me know what you think of these changes. I also took a look at all the other indent scripts shipped with Vim by default and noted that none of them edit formatoptions.

February 7, 2011This picture snapped in Paris, two blocks from the apartment I holed up in. Some background.

February 4, 2011I spent some time fleshing out my count min sketch implementation for OCaml (to be the subject of another blog post), and along the way, I noticed a few more quirks about the OCaml language (from a Haskell viewpoint).

Unlike Haskell’s Int, which is 32-bit/64-bit, the built-in OCaml int type is only 31-bit/63-bit. Bit twiddlers beware! (There is a nativeint type which gives full machine precision, but it less efficient than the int type).

Semicolons have quite different precedence from the “programmable semicolon” of a Haskell do-block. In particular:

let rec repeat n thunk =

if n == 0 then ()

else thunk (); repeat (n-1) thunk

doesn’t do what you’d expect similarly phrased Haskell. (I hear I’m supposed to use begin and end.)

You can only get 30-bits of randomness from the Random module (an positive integer using Random.bits), even when you’re on a 64-bit platform, so you have to manually stitch multiple invocations to the generator together.

I don’t like a marching staircase of indentation, so I hang my “in”s after their statements—however, when they’re placed there, they’re easy to forget (since a let in a do-block does not require an in in Haskell).

Keyword arguments are quite useful, but they gunk up the type system a little and make it a little more difficult to interop keyword functions and non-keyword functions in a higher-order context. (This is especially evident when you’re using keyword arguments for documentation purposes, not because your function takes two ints and you really do need to disambiguate them.)

One observation about purity and randomness: I think one of the things people frequently find annoying in Haskell is the fact that randomness involves mutation of state, and thus be wrapped in a monad. This makes building probabilistic data structures a little clunkier, since you can no longer expose pure interfaces. OCaml is not pure, and as such you can query the random number generator whenever you want.

However, I think Haskell may get the last laugh in certain circumstances. In particular, if you are using a random number generator in order to generate random test cases for your code, you need to be able to reproduce a particular set of random tests. Usually, this is done by providing a seed which you can then feed back to the testing script, for deterministic behavior. But because OCaml’s random number generator manipulates global state, it’s very easy to accidentally break determinism by asking for a random number for something unrelated. You can work around it by manually bracketing the global state, but explicitly handling the randomness state means providing determinism is much more natural.

February 2, 2011I recently took the time out to rewrite the MVar documentation, which as it stands is fairly sparse (the introduction section rather tersely states “synchronising variables”; though to the credit of the original writers the inline documentation for the data type and its fundamental operations is fairly fleshed out.) I’ve reproduced my new introduction here.

While researching this documentation, I discovered something new about how MVars worked, which is encapsulated in this program. What does it do? :

import Control.Concurrent.MVar

import Control.Concurrent

main = do

x <- newMVar 0

forkIO $ do

putMVar x 1

putStrLn "child done"

threadDelay 100

readMVar x

putStrLn "parent done"

An MVar t is mutable location that is either empty or contains a value of type t. It has two fundamental operations: putMVar which fills an MVar if it is empty and blocks otherwise, and takeMVar which empties an MVar if it is full and blocks otherwise. They can be used in multiple different ways:

- As synchronized mutable variables,

- As channels, with

takeMVar and putMVar as receive and send, and - As a binary semaphore

MVar (), with takeMVar and putMVar as wait and signal.

They were introduced in the paper “Concurrent Haskell” by Simon Peyton Jones, Andrew Gordon and Sigbjorn Finne, though some details of their implementation have since then changed (in particular, a put on a full MVar used to error, but now merely blocks.)

MVars offer more flexibility than IORefs, but less flexibility than STM. They are appropriate for building synchronization primitives and performing simple interthread communication; however they are very simple and susceptible to race conditions, deadlocks or uncaught exceptions. Do not use them if you need perform larger atomic operations such as reading from multiple variables: use ‘STM’ instead.

In particular, the “bigger” functions in this module (readMVar, swapMVar, withMVar, modifyMVar_ and modifyMVar) are simply compositions a takeMVar followed by a putMVar with exception safety. These only have atomicity guarantees if all other threads perform a takeMVar before a putMVar as well; otherwise, they may block.

The original paper specified that no thread can be blocked indefinitely on an MVar unless another thread holds that MVar indefinitely. This implementation upholds this fairness property by serving threads blocked on an MVar in a first-in-first-out fashion.

Like many other Haskell data structures, MVars are lazy. This means that if you place an expensive unevaluated thunk inside an MVar, it will be evaluated by the thread that consumes it, not the thread that produced it. Be sure to evaluate values to be placed in an MVar to the appropriate normal form, or utilize a strict MVar provided by the strict-concurrency package.

Consider the following concurrent data structure, a skip channel. This is a channel for an intermittent source of high bandwidth information (for example, mouse movement events.) Writing to the channel never blocks, and reading from the channel only returns the most recent value, or blocks if there are no new values. Multiple readers are supported with a dupSkipChan operation.

A skip channel is a pair of MVars: the second MVar is a semaphore for this particular reader: it is full if there is a value in the channel that this reader has not read yet, and empty otherwise.

import Control.Concurrent.MVar

import Control.Concurrent

data SkipChan a = SkipChan (MVar (a, [MVar ()])) (MVar ())

newSkipChan :: IO (SkipChan a)

newSkipChan = do

sem <- newEmptyMVar

main <- newMVar (undefined, [sem])

return (SkipChan main sem)

putSkipChan :: SkipChan a -> a -> IO ()

putSkipChan (SkipChan main _) v = do

(_, sems) <- takeMVar main

putMVar main (v, [])

mapM_ (\sem -> putMVar sem ()) sems

getSkipChan :: SkipChan a -> IO a

getSkipChan (SkipChan main sem) = do

takeMVar sem

(v, sems) <- takeMVar main

putMVar main (v, sem:sems)

return v

dupSkipChan :: SkipChan a -> IO (SkipChan a)

dupSkipChan (SkipChan main _) = do

sem <- newEmptyMVar

(v, sems) <- takeMVar main

putMVar main (v, sem:sems)

return (SkipChan main sem)

This example was adapted from the original Concurrent Haskell paper. For more examples of MVars being used to build higher-level synchronization primitives, see Control.Concurrent.Chan and Control.Concurrent.QSem.

December 31, 2010Here is to celebrate a year of blogging. Thank you all for reading. It was only a year ago that I first opened up shop under the wings of Iron Blogger. Iron Blogger has mostly disintegrated at this point, but I’m proud to say that this blog has not, publishing thrice a week, every week (excepting that one time I missed a post and made it up with a bonus post later that month), a bet that I made with myself and am happy to have won.

Where has this blog gone over the year? According to Google Analytics, here were the top ten most viewed posts:

- Graphs not grids: How caches are corrupting young algorithms designers and how to fix it

- You could have invented zippers

- Medieval medicine and computers

- Databases are categories

- Design Patterns in Haskell

- Static Analysis for everday (not-PhD) man

- MVC and purity

- Day in the life of a Galois intern

- Replacing small C programs with Haskell

- How to use Vim’s textwidth like a pro

There are probably a few obscure ones that are my personal favorites, but I’ve written so many at this point it’s a little hard to count: including this post, I will have published 159 posts, totaling somewhere around 120,000 words. (This figure includes markup, but for comparison, a book is about 80,000 words. Holy cow, I’ve written a book and a half worth of content. I don’t really feel like a better writer though—this may be because I’ve skimped on the “revising” bit of the process.)

This blog will go on a brief hiatus for the month of January. Not because I wouldn’t be able to produce posts over the holidays (given the chance, I probably would… in fact, this was a kind of hard decision to make) but because I should spend a month concentrating the bulk of my free time on stuff other than blogging. Have a happy New Years, and see you in February!

Postscript. Here is the SQL query I used to count:

select

sum( length(replace(post_content, ' ', '')) - length(replace(post_content, ' ', ''))+1)

from wp_posts

where post_status = 'publish';

There’s probably a more accurate way of doing it, but I was too lazy to write out the script.

December 29, 2010“Roughing it,” so to speak.

With no reservations and no place to go, the hope was to crash somewhere in the Jungfrau region above the “fogline”

but these plans were thwarted by my discovery that Wengen had no hostels. Ah well.

Still pretty.

Of which I do not have a photo, one of the astonishing sights from Lauterbrunnen at night (I checked in and asked the owner, “Any open beds?” They replied, “One!” Only one possible response: “Excellent!”) is that the towns and trains interspersed on the mountains almost look like stars (the mountain hidden from view, due to their sparseness), clustered together in chromatic galaxies.

Non sequitur. A question for the readers: “What is a solution you have that is in search of a problem?”

December 27, 2010New to this series? Start at the beginning!

Recursion is perhaps one of the first concepts you learn about when you learn functional programming (or, indeed, computer science, one hopes.) The classic example introduced is factorial:

fact :: Int -> Int

fact 0 = 1 -- base case

fact n = n * fact (pred n) -- recursive case

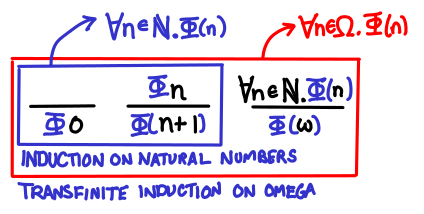

Recursion on natural numbers is closely related to induction on natural numbers, as is explained here.

One thing that’s interesting about the data type Int in Haskell is that there are no infinities involved, so this definition works perfectly well in a strict language as well as a lazy language. (Remember that Int is a flat data type.) Consider, however, Omega, which we were playing around with in a previous post: in this case, we do have an infinity! Thus, we also need to show that factorial does something sensible when it is passed infinity: it outputs infinity. Fortunately, the definition of factorial is precisely the same for Omega (given the appropriate typeclasses.) But why does it work?

One operational answer is that any given execution of a program will only be able to deal with a finite quantity: we can’t ever actually “see” that a value of type Omega is infinity. Thus if we bound everything by some large number (say, the RAM of our computer), we can use the same reasoning techniques that applied to Int. However, I hope that you find something deeply unsatisfying about this answer: you want to think of an infinite data type as infinite, even if in reality you will never need the infinity. It’s the natural and fluid way to reason about it. As it turns out, there’s an induction principle to go along with this as well: transfinite induction.

recursion on natural numbers - induction

recursion on Omega - transfinite induction

Omega is perhaps not a very interesting data type that has infinite values, but there are plenty of examples of infinite data types in Haskell, infinite lists being one particular example. So in fact, we can generalize both the finite and infinite cases for arbitrary data structures as follows:

recursion on finite data structures - structural induction

recursion on infinite data structures - Scott induction

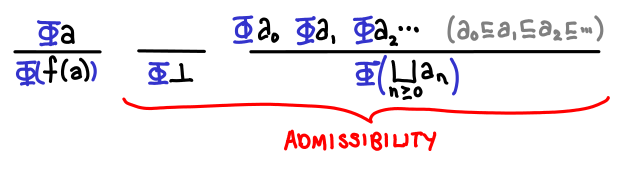

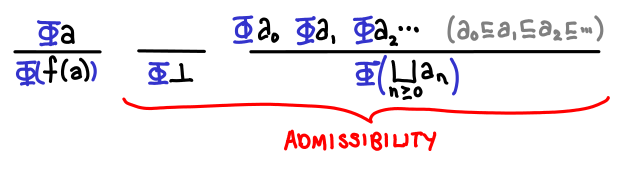

Scott induction is the punch line: with it, we have a versatile tool for reasoning about the correctness of recursive functions in a lazy language. However, its definition straight up may be a little hard to digest:

Let D be a cpo. A subset S of D is chain-closed if and only if for all chains in D, if each element of the chain is in S, then the least upper bound of the chain is in S as well. If D is a domain, a subset S is admissible if it is chain-closed and it contains bottom. Scott’s fixed point induction principle states that to prove that fix(f) is in S, we merely need to prove that for all d in D, if d is in S, then f(d) is in S.

When I first learned about Scott induction, I didn’t understand why all of the admissibility stuff was necessary: it was explained to me to be “precisely the stuff necessary to make the induction principle work.” I ended up coming around to this point of view in the end, but it’s a little hard to see in its full generality.

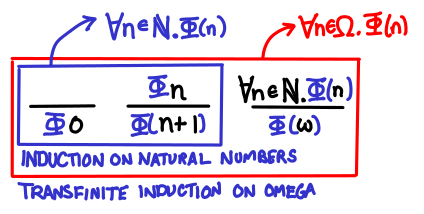

So, in this post, we’ll show how the jump from induction on natural numbers to transfinite induction corresponds to the jump from structural induction to Scott induction.

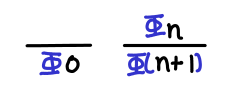

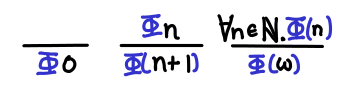

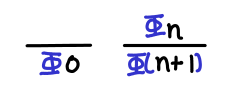

Induction on natural numbers. This is the induction you learn on grade school and is perhaps the simplest form of induction. As a refresher, it states that if some property holds for when n = 0, and if some property holds for n + 1 given that it holds for n, then the property holds for all natural numbers.

One way of thinking of the base case and the inductive step is to see them as inference rules that we need to show are true: if they are, we get another inference rule that lets us sidestep the infinite applications of the inductive step that would be necessary to satisfy ourselves that the property holds for all natural numbers. (Note that there is on problem if we only want to show that the property holds for an arbitrary natural number: that only requires a finite number of applications of the inductive step!)

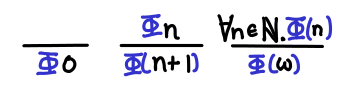

Transfinite induction on Omega. Recall that Omega is the natural numbers plus the smallest infinite ordinal ω. Suppose that we wanted to prove that some property held for all natural numbers as well as infinity. If we just used induction on natural numbers, we’d notice that we’d be able to prove the property for some finite natural number, but not necessarily for infinity (for example, we might conclude that every natural number has another number greater than it, but there is no value in Omega greater than infinity).

This means we need one case: given that a property holds for all natural numbers, it holds for ω as well. Then we can apply induction on natural numbers and then infer that the property holds for infinity as well.

We notice that transfinite induction on Omega requires strictly more cases to be proven than induction on natural numbers, and as such is able to draw stronger conclusions.

Aside. In its full generality, we may have many infinite ordinals, and so the second case generalizes to successor ordinals (e.g. adding 1) and the third case generalizes to limit ordinal (that is, an ordinal that cannot be reached by repeatedly applying the successor function a finite number of times—e.g. infinity from zero). Does this sound familiar? I hope it does: this notion of a limit should remind you of the least upper bounds of chains (indeed, ω is the least upper bound of the only nontrivial chain in the domain Omega).

Let’s take a look at the definition of Scott induction again:

Let D be a cpo. A subset S of D is chain-closed if and only if for all chains in D, if each element of the chain is in S, then the least upper bound of the chain is in S as well. If D is a domain, a subset S is admissible if it is chain-closed and it contains bottom. Scott’s fixed point induction principle states that to prove that fix(f) is in S, we merely need to prove that for all d in D, if d is in S, then f(d) is in S.

We can now pick out the parts of transfinite induction that correspond to statements in this definition. S corresponds to the set of values with the property we want to show, so S = {d | d in D and prop(d)} The base case is the inclusion of bottom in S. The successor case is “if d is in S, then f(d) is in S” (notice that f is our successor function now, not the addition of one). And the limit case corresponds to the chain-closure condition.

Here are all of the inference rules we need to show!

The domain D that we would use to prove that factorial is correct on Omega is the domain of functions Omega -> Omega, the successor function is (Omega -> Omega) -> (Omega -> Omega), and the subset S would correspond to the chain of increasingly defined versions of factorial. With all these ingredients in hand, we can see that fix(f) is indeed the factorial function we are looking for.

There are a number of interesting “quirks” about Scott induction. One is the fact that the property must hold for bottom, which is a partial correctness result (“such and such holds if the program terminates”) rather than a total correctness result (“the program terminates AND such and such holds”). The other is that the successor case is frequently not the most difficult part of a proof involving Scott induction: showing admissibility of your property is.

This concludes our series on denotational semantics. This is by no means complete: usually the next thing to look at is a simple functional programming language called PCF, and then relate the operational semantics and denotational semantics of this language. But even if you decide that you don’t want to hear any more about denotational semantics, I hope these glimpses into this fascinating world will help you reason about laziness in your Haskell programs.

Postscript. I originally wanted to relate all these forms of inductions to generalized induction as presented in TAPL: the inductive principle is that the least fixed point of a monotonic function F : P(U) -> P(U) (where P(U) denotes the powerset of the universe) is the intersection of all F-closed subsets of U. But this lead to the rather interesting situation where the greatest fixed points of functions needed to accept sets of values, and not just a single value. I wasn’t too sure what to make of this, so I left it out.

Unrelatedly, it would also be nice, for pedagogical purposes, to have a “paradox” that arises from incorrectly (but plausibly) applying Scott induction. Alas, such an example eluded me at the time of writing.

December 24, 2010How do you decide what to work on? I started thinking about this topic when I was wasting time on the Internet because I couldn’t think of anything to do that was productive. This seemed kind of strange: there were lots of things I needed to do: vacations to plan, projects to work on, support requests to answer, patches to merge in, theorems to prove, blog posts to write, papers to read, etc. So maybe the problem wasn’t that I didn’t have anything to do, it was just that I had too much stuff to do, and that I needed to pick something.

This choice is nontrivial. That evening, I didn’t feel like organizing my priorities either, so I just ended up just reading some comics, rationalizing it—erm, I mean filing it—under “Rest and Relaxation.” I could have chosen what to do based on some long term plan… yeah right, like I have a long time plan. It seems more practical to have chosen to do something enjoyable (which, when not involving reading comics, can occasionally involve productive work), or something that would give me a little high at the end, a kind of thrill from finishing—not necessarily fun when starting off, but fulfilling and satisfying by the end.

So what’s thrilling? In the famous book The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, Thomas Kuhn argued that what most scientists do is “normal science”, problem solving in the current field without any expectation of making revolutionary discoveries or changing the way we do science. This is a far cry from the idealistic vision ala “When I grow up, I want to be a scientist and discover a cure for cancer”—it would truly be thrilling to manage that. But if the life of an ordinary scientist is so mundane and so unlikely to result in a revolution, why do incredibly smart people dedicate their lives in the pursuit of scientific knowledge? What is thrilling about science?

Kuhn suggests that this may because humans love solving puzzles, and science is the ultimate puzzle solving activity: there is some hitherto unexplained phenomena, and a scientist attempts fit this phenomena into the existing theories and paradigms. And so while the average person may not find the in-depth analysis of a single section of DNA of a single obscure virus very interesting, for the scientist this generates endless puzzles for them to solve, each step of the way adding some knowledge, however small, to our civilization. And we humans find puzzles thrilling: they occupy us and give us that satisfaction when they are solved.

For a software engineer, the thrill may be in the creation of something that works and is useful to others (the rush of having users) or the thrill may be in having solved a particularly tricky problem (the rush that comes after you solve a tricky debugging session, or the rush when you do something very clever). The types of thrill you prefer dictate the kind of learning you are interested in. If you seek the thrill of creation, you will work on gaining the specialized knowledge of specific tools, libraries and applications that you will need in your craft. You will pursue knowledge outside of mere “programming”: aesthetics, design, psychology, marketing and more: the creation of a product is a truly interdisciplinary problem. If you seek the thrill of debugging (the hacker), you will seek specialized knowledge of a different kind, painstaking knowledge of the wire structure of protocols, source code, memory layout, etc. And if you seek the thrill of scientific problem solving, you will seek generalized, abstract knowledge, knowledge that suggests new ways of thinking about and doing things.

The steps towards each type of thrill are interrelated, but only to a certain degree. I remember a graduate student once telling me, “If you really want to make sure you understand something, you should go implement it. But sometimes this is counterproductive, because you spend so much time trying to make it work that you forget about the high level principles involved.” In this mindset, something becomes clear: not all knowledge is created equal. The first time I learn how to use a web framework, I acquire generalist knowledge—how a web framework might be put together, what functionality it is supposed to have and design idioms—as well as specialist knowledge—how this particular web framework works. But the next time I learn a different web framework, the generalist knowledge I gain is diminished. Repeat enough times, and all that’s left are implementation details: there is no element of surprise. (One caveat: at the limit, learning many, many web frameworks can give you some extra generalist knowledge simply by virtue of having seen so much. We might call this experience.)

For me, this presents an enormous conundrum. I want to create things! But creation requires contiguous chunks of time, which are rare and precious, and requires a constellation of generalist knowledge (the idea) and specialist knowledge (the details). So when I don’t have several weeks to devote to a single project (aka never), what should I do?

I’m not sure what I should do, but I have a vague sense for what my current rut is: alternate between working on projects that promise to give some generalist knowledge (whether it’s a short experiment for a blog post or hacking in the majestic mindbending landscape that is GHC) and slugging through my specialist maintenance workload. It… works, although it means I do a bit more writing and system administration than coding these days. C’est la vie.