April 24, 2011In today’s post, we focus on you, the unwitting person rooting around the Haskell heap to open a present. After all, presents in the Haskell heap do not spontaneously unwrap themselves.

Someone has to open the first present.

If the Haskell heap doesn’t interact with the outside world, no presents need to be opened: thus IO functions are the ones that will open presents. What presents they will open is not necessarily obvious for many functions, so we’ll focus on one function that makes it particularly obvious: evaluate. Which tells you to…

…open a present.

If you get a primitive value, you’re done. But, of course, you might get a gift card (constructor):

Will you open the rest of the presents? Despite that deep, dissatisfaction inside you, the answer is no. evaluate only asks you to open one present. If it’s already opened, there’s nothing for you to do.

Advanced tip: If you want to evaluate more things, make a present containing a ghost who will open those things for you! A frequently used example of this when lazy IO is involved was evaluate (length xs), but don’t worry too much if you don’t understand that yet: I haven’t actually said how we make presents yet!

Even though we’re only opening one present, many things can happen, as described in the last post. It could execute some IO…

This is our direct window into evaluation as it evolves: when we run programs normally, we can’t see the presents being opened up; but if we ask the ghost to also shout out when it is disturbed, we get back this information. And in fact, this is precisely what Debug.Trace does!

There are other ways to see what evaluation is going on. A present could blow up: this is the exploding booby-trapped present, also known as “bottom”.

Perhaps the explosion was caused by an undefined or error "Foobar".

Boom.

We’ll end on a practical note. As we’ve mentioned, you can only be sure that a present has been opened if you’ve explicitly asked for it to be opened from IO. Otherwise, ghosts might play tricks on you. After all, you can’t actually see the Haskell heap, so there’s no way to directly tell if a present has been opened or not.

If you’re unsure when a thunk is being evaluated, add a trace statement to it. If ghosts are being lazy behind your back, the trace statement will never show up.

More frequently, however, the trace statement will show up; it’ll just be later than you expect (the ghosts may be lazy, but they’ll eventually get the job done.) So it’s useful to prematurely terminate your program or add extra print statements demarcating various stages of your program.

Last time: Evaluation on the Haskell Heap

Next time: Implementing the Haskell Heap in Python, v1

Technical notes. Contrary to what I’ve said earlier, there’s no theoretical reason why we couldn’t spontaneously evaluate thunks on the heap: this evaluation approach is called speculative evaluation. Somewhat confusingly, IO actions themselves can be thunks as well: this corresponds to passing around values of IO a without actually “running” them. But since I’m not here to talk about monads, I’ll simply ignore the existence of presents that contain IO actions—they work the same way, but you have to keep the levels of indirection straight. And finally, of course infinite loops also count as bottom, but the image of opening one present for the rest of eternity is not as flashy as an exploding present.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

April 20, 2011

The Ghost of the Christmas Present

In today’s post, we’ll do a brief survey of the various things that can happen when you open haunted presents in the Haskell heap. Asides from constants and things that have already been evaluated, mostly everything on the Haskell heap is haunted. The real question is what the ghost haunting the present does.

In the simplest case, almost nothing!

Unlike gift-cards, you have to open the next present (Haskell doesn’t let you evaluate a thunk, and then decide not to follow the indirection…)

More commonly, the ghost was lazy and, when woken up, has to open other presents to figure out what was in your present in the first place!

Simple primitive operations need to open all of the presents involved.

But the ghost may also open another present for no particular reason…

or execute some IO…

Note that any presents he opens may trigger more ghosts:

Resulting in a veritable ghost jamboree, all to open one present!

The fact that opening a present (thunk) can cause such a cascading effect is precisely what makes the timing of lazy evaluation surprising to people who are used to all of the objects in their heap being unwrapped (evaluated) already. So the key to getting rid of this surprise is understanding when a ghost will decide it needs to unwrap a present (strictness analysis) and whether or not your presents are unwrapped already (amortized analysis).

Last time: The Haskell Heap

Next time: IO evaluates the Haskell Heap

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

April 18, 2011

The Haskell heap is a rather strange place. It’s not like the heap of a traditional, strictly evaluated language…

…which contains a lot of junk! (Plain old data.)

In the Haskell heap, every item is wrapped up nicely in a box: the Haskell heap is a heap of presents (thunks).

When you actually want what’s inside the present, you open it up (evaluate it).

Presents tend to have names, and sometimes when you open a present, you get a gift card (data constructor). Gift cards have two traits: they have a name (the Just gift card or the Right gift card), and they tell you where the rest of your presents are. There might be more than one (the tuple gift card), if you’re a lucky duck!

But just as gift cards can lie around unused (that’s how the gift card companies make money!), you don’t have to redeem those presents.

Presents on the Haskell heap are rather mischievous. Some presents explode when you open them, others are haunted by ghosts that open other presents when disturbed.

Understanding what happens when you open a present is key to understanding the time and space behavior of Haskell programs.

In this series, Edward makes a foray into the webcomic world in order to illustrate the key operational concepts of evaluation in a lazily evaluated language. I hope you enjoy it!

Next time: Evaluation on the Haskell Heap

Technical notes. Technically speaking, this series should be “The GHC Heap.” However, I’ll try to avoid as many GHC-isms as possible, and simply offer a metaphor for operationally reasoning about any kind of lazy language. Originally, the series was titled “Bomberman Teaches Lazy Evaluation,” but while I’ve preserved the bomb metaphor for thunks that error or don’t terminate, I like the present metaphor better: it in particular captures several critical aspects of laziness: it captures the evaluated/non-evaluated distinction and the fact that once a present is opened, it’s opened for everyone. The use of the term “boxed” is a little suggestive: indeed, boxed or lifted values in GHC are precisely the ones that can be nonterminating, whereas unboxed values are more akin to what you’d see in C’s heap. However, languages like Java also use the term boxed to refer to primitive values that look like objects. For clarity’s sake, we won’t be using the term boxed from now on (indeed, we won’t mention unboxed types).

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

April 16, 2011What is the Mailbox? It’s a selection of interesting email conversations from my mailbox, which I can use in place of writing original content when I’m feeling lazy. I got the idea from Matt Might, who has a set of wonderful suggestions for low-cost academic blogging.

From: Brent Yorgey

I see you are a contributor to the sup mail client. At least I assume it is you, I doubt there are too many Edward Z. Yangs in the world. =) I’m thinking of switching from mutt. Do you still use sup? Any thoughts/encouragements/cautions to share?

To: Brent Yorgey

Yeah! I still use Sup, and I’ve blogged a little about it in the past, which is still essentially the setup I use. Hmm, some notes:

- I imagine that you want to switch away from Mutt because of some set of annoyances that has finally gotten unbearable. I will warn you that no mail client is perfect; many of my friends used to use Sup and gave up on it along the way. (I hear they use GMail now.) I’ve stuck it out, partially due to inertia, partially because someone else took ezyang@gmail.com, but also partially because I think it’s worth it :-)

- One of the things that has most dramatically changed the way I read email is the distinction between inbox and unread, and not-inbox and unread. In particular, while I have a fairly extensive set of filters that tag mail I get from mailing lists, when I read things on a day to day basis, I check my inbox for important stuff, and then I check my not-inbox “for fun”, mostly not reading most emails (but skimming the subject headers.) This means checking my mail in the morning is about a ten minute deal. This is the deal-maker for me.

- You will almost definitely want to setup OfflineIMAP, because downloading a 80 message thread from the Internet gets old very quickly. But Sup doesn’t propagate back changes to your mailbox this way (in particular, ‘read’ in Sup doesn’t mean ‘read’ in your INBOX) unless you use some experimental code on the maildir-sync branch. I’ve been using it for some time now quite well, but it does make getting other upstream changes a bit of an ordeal.

- Getting Sup setup will take some time; the initial import takes a long time and tweaking also takes a bit of time. Make sure you don’t have any deadlines coming soon. I’ve also found that it’s not really possible to use Sup without dipping your hand into some Ruby hacking (though maybe that’s just me :-); right now I have four hand-crafted patches on top of my source tree, and rebasing to master is not something done likely. I’ve actually gotten into a bit of trouble being so hack happy, but it’s also nice to be able to fix things when you need to (Sup not working is /very/ disruptive). Unfortunately, Ruby is not statically typed. :-)

Hope that helps. Do feel free to shout out if you need some help.

April 13, 2011It is often said that the factorial function is the “Hello World!” of the functional programming language world. Indeed, factorial is a singularly useful way of testing the pattern matching and recursive facilities of FP languages: we don’t bother with such “petty” concerns as input-output. In this blog post, we’re going to trace the compilation of factorial through the bowels of GHC. You’ll learn how to read Core, STG and Cmm, and hopefully get a taste of what is involved in the compilation of functional programs. Those who would like to play along with the GHC sources can check out the description of the compilation of one module on the GHC wiki. We won’t compile with optimizations to keep things simple; perhaps an optimized factorial will be the topic of another post!

The examples in this post were compiled with GHC 6.12.1 on a 32-bit Linux machine.

$ cat Factorial.hs

We start in the warm, comfortable land of Haskell:

module Factorial where

fact :: Int -> Int

fact 0 = 1

fact n = n * fact (n - 1)

We don’t bother checking if the input is negative to keep the code simple, and we’ve also specialized this function on Int, so that the resulting code will be a little clearer. But other then that, this is about as standard Factorial as it gets. Stick this in a file called Factorial.hs and you can play along.

$ ghc -c Factorial.hs -ddump-ds

Haskell is a big, complicated language with lots of features. This is important for making it pleasant to code in, but not so good for machine processing. So once we’ve got the majority of user visible error handling finished (typechecking and the like), we desugar Haskell into a small language called Core. At this point, the program is still functional, but it’s a bit wordier than what we originally wrote.

We first see the Core version of our factorial function:

Rec {

Factorial.fact :: GHC.Types.Int -> GHC.Types.Int

LclIdX

[]

Factorial.fact =

\ (ds_dgr :: GHC.Types.Int) ->

let {

n_ade :: GHC.Types.Int

LclId

[]

n_ade = ds_dgr } in

let {

fail_dgt :: GHC.Prim.State# GHC.Prim.RealWorld -> GHC.Types.Int

LclId

[]

fail_dgt =

\ (ds_dgu :: GHC.Prim.State# GHC.Prim.RealWorld) ->

*_agj n_ade (Factorial.fact (-_agi n_ade (GHC.Types.I# 1))) } in

case ds_dgr of wild_B1 { GHC.Types.I# ds_dgs ->

letrec { } in

case ds_dgs of ds_dgs {

__DEFAULT -> fail_dgt GHC.Prim.realWorld#; 0 -> GHC.Types.I# 1

}

}

This may look a bit foreign, so here is the Core re-written in something that has more of a resemblance to Haskell. In particular I’ve elided the binder info (the type signature, LclId and [] that precede every binding), removed some type signatures and reindented:

Factorial.fact =

\ds_dgr ->

let n_ade = ds_dgr in

let fail_dgt = \ds_dgu -> n_ade * Factorial.fact (n_ade - (GHC.Int.I# 1)) in

case ds_dgr of wild_B1 { I# ds_dgs ->

case ds_dgs of ds_dgs {

__DEFAULT -> fail_dgt GHC.Prim.realWorld#

0 -> GHC.Int.I# 1

}

}

It’s still a curious bit of code, so let’s step through it.

- There are no longer

fact n = ... style bindings: instead, everything is converted into a lambda. We introduce anonymous variables prefixed by ds_ for this purpose. - The first let-binding is to establish that our variable

n (with some extra stuff tacked on the end, in case we had defined another n that shadowed the original binding) is indeed the same as ds_dgr. It will get optimized away soon. - Our recursive call to

fact has been mysteriously placed in a lambda with the name fail_dgt. What is the meaning of this? It’s an artifact of the pattern matching we’re doing: if all of our other matches fail (we only have one, for the zero case), we call fail_dgt. The value it accepts is a faux-token GHC.Prim.realWorld#, which you can think of as unit. - We see that our pattern match has been desugared into a case-statement on the unboxed value of

ds_dgr, ds_dgs. We do one case switch to unbox it, and then another case switch to do the pattern match. There is one extra bit of syntax attached to the case statements, a variable to the right of the of keyword, which indicates the evaluated value (in this particular case, no one uses it.) - Finally, we see each of the branches of our recursion, and we see we have to manually construct a boxed integer

GHC.Int.I# 1 for literals.

And then we see a bunch of extra variables and functions, which represent functions and values we implicitly used from Prelude, such as multiplication, subtraction and equality:

$dNum_agq :: GHC.Num.Num GHC.Types.Int

LclId

[]

$dNum_agq = $dNum_agl

*_agj :: GHC.Types.Int -> GHC.Types.Int -> GHC.Types.Int

LclId

[]

*_agj = GHC.Num.* @ GHC.Types.Int $dNum_agq

-_agi :: GHC.Types.Int -> GHC.Types.Int -> GHC.Types.Int

LclId

[]

-_agi = GHC.Num.- @ GHC.Types.Int $dNum_agl

$dNum_agl :: GHC.Num.Num GHC.Types.Int

LclId

[]

$dNum_agl = GHC.Num.$fNumInt

$dEq_agk :: GHC.Classes.Eq GHC.Types.Int

LclId

[]

$dEq_agk = GHC.Num.$p1Num @ GHC.Types.Int $dNum_agl

==_adA :: GHC.Types.Int -> GHC.Types.Int -> GHC.Bool.Bool

LclId

[]

==_adA = GHC.Classes.== @ GHC.Types.Int $dEq_agk

fact_ado :: GHC.Types.Int -> GHC.Types.Int

LclId

[]

fact_ado = Factorial.fact

end Rec }

Since +, * and == are from type classes, we have to lookup the dictionary for each type dNum_agq and dEq_agk, and then use this to get our actual functions *_agj, -_agi and ==_adA, which are what our Core references, not the fully generic versions. If we hadn’t provided the Int -> Int type signature, this would have been a bit different.

ghc -c Factorial.hs -ddump-simpl

From here, we do a number of optimization passes on the core. Keen readers may have noticed that the unoptimized Core allocated an unnecessary thunk whenever n = 0, the fail_dgt. This inefficiency, among others, is optimized away:

Rec {

Factorial.fact :: GHC.Types.Int -> GHC.Types.Int

GblId

[Arity 1]

Factorial.fact =

\ (ds_dgr :: GHC.Types.Int) ->

case ds_dgr of wild_B1 { GHC.Types.I# ds1_dgs ->

case ds1_dgs of _ {

__DEFAULT ->

GHC.Num.*

@ GHC.Types.Int

GHC.Num.$fNumInt

wild_B1

(Factorial.fact

(GHC.Num.-

@ GHC.Types.Int GHC.Num.$fNumInt wild_B1 (GHC.Types.I# 1)));

0 -> GHC.Types.I# 1

}

}

end Rec }

Now, the very first thing we do upon entry is unbox the input ds_dgr and pattern match on it. All of the dictionary nonsense has been inlined into the __DEFAULT branch, so GHC.Num.* @ GHC.Types.Int GHC.Num.$fNumInt corresponds to multiplication for Int, and GHC.Num.- @ GHC.Types.Int GHC.Num.$fNumInt corresponds to subtraction for Int. Equality is nowhere to be found, because we could just directly pattern match against an unboxed Int.

There are a few things to be said about boxing and unboxing. One important thing to notice is that the case statement on ds_dgr forces this variable: it may have been a thunk, so some (potentially large) amount of code may run before we proceed any further. This is one of the reasons why getting backtraces in Haskell is so hard: we care about where the thunk for ds_dgr was allocated, not where it gets evaluated! But we don’t know that it’s going to error until we evaluate it.

Another important thing to notice is that although we unbox our integer, the result ds1_dgs is not used for anything other than pattern matching. Indeed, whenever we would have used n, we instead use wild_B1, which corresponds to the fully evaluated version of ds_dgr. This is because all of these functions expect boxed arguments, and since we already have a boxed version of the integer lying around, there’s no point in re-boxing the unboxed version.

ghc -c Factorial.hs -ddump-stg

Now we convert Core to the spineless, tagless, G-machine, the very last representation before we generate code that looks more like a traditional imperative program.

Factorial.fact =

\r srt:(0,*bitmap*) [ds_sgx]

case ds_sgx of wild_sgC {

GHC.Types.I# ds1_sgA ->

case ds1_sgA of ds2_sgG {

__DEFAULT ->

let {

sat_sgJ =

\u srt:(0,*bitmap*) []

let {

sat_sgI =

\u srt:(0,*bitmap*) []

let { sat_sgH = NO_CCS GHC.Types.I#! [1];

} in GHC.Num.- GHC.Num.$fNumInt wild_sgC sat_sgH;

} in Factorial.fact sat_sgI;

} in GHC.Num.* GHC.Num.$fNumInt wild_sgC sat_sgJ;

0 -> GHC.Types.I# [1];

};

};

SRT(Factorial.fact): [GHC.Num.$fNumInt, Factorial.fact]

Structurally, STG is very similar to Core, though there’s a lot of extra goop in preparation for the code generation phase:

- All of the variables have been renamed,

- All of the lambdas now have the form

\r srt:(0,*bitmap*) [ds_sgx]. The arguments are in the list at the rightmost side: if there are no arguments this is simply a thunk. The first character after the backslash indicates whether or not the closure is re-entrant (r), updatable (u) or single-entry (s, not used in this example). Updatable closures can be rewritten after evaluation with their results (so closures that take arguments can’t be updateable!) Afterwards, the static reference table is displayed, though there are no interesting static references in our program. NO_CCS is an annotation for profiling that indicates that no cost center stack is attached to this closure. Since we’re not compiling with profiling it’s not very interesting.- Constructor applications take their arguments in square brackets:

GHC.Types.I# [1]. This is not just a stylistic change: in STG, constructors are required to have all of their arguments (e.g. they are saturated). Otherwise, the constructor would be turned into a lambda.

There is also an interesting structural change, where all function applications now take only variables as arguments. In particular, we’ve created a new sat_sgJ thunk to pass to the recursive call of factorial. Because we have not compiled with optimizations, GHC has not noticed that the argument of fact will be immediately evaluated. This will make for some extremely circuitous intermediate code!

ghc -c Factorial.hs -ddump-cmm

Cmm (read “C minus minus”) is GHC’s high-level assembly language. It is similar in scope to LLVM, although it looks more like C than assembly. Here the output starts getting large, so we’ll treat it in chunks. The Cmm output contains a number of data sections, which mostly encode the extra annotated information from STG, and the entry points: sgI_entry, sgJ_entry, sgC_ret and Factorial_fact_entry. There are also two extra functions __stginit_Factorial_ and __stginit_Factorial which initialize the module, that we will not address.

Because we have been looking at the STG, we can construct a direct correspondence between these entry points and names from the STG. In brief:

sgI_entry corresponded to the thunk that subtracted 1 from wild_sgC. We’d expect it to setup the call to the function that subtracts Int.sgJ_entry corresponded to the thunk that called Factorial.fact on sat_sgI. We’d expect it to setup the call to Factorial.fact.sgC_ret is a little different, being tagged at the end with ret. This is a return point, which we will return to after we successfully evaluate ds_sgx (i.e. wild_sgC). We’d expect it to check if the result is 0, and either “return” a one (for some definition of “return”) or setup a call to the function that multiplies Int with sgJ_entry and its argument.

Time for some code! Here is sgI_entry:

sgI_entry()

{ has static closure: False update_frame: <none>

type: 0

desc: 0

tag: 17

ptrs: 1

nptrs: 0

srt: (Factorial_fact_srt,0,1)

}

ch0:

if (Sp - 24 < SpLim) goto ch2;

I32[Sp - 4] = R1; // (reordered for clarity)

I32[Sp - 8] = stg_upd_frame_info;

I32[Sp - 12] = stg_INTLIKE_closure+137;

I32[Sp - 16] = I32[R1 + 8];

I32[Sp - 20] = stg_ap_pp_info;

I32[Sp - 24] = base_GHCziNum_zdfNumInt_closure;

Sp = Sp - 24;

jump base_GHCziNum_zm_info ();

ch2: jump stg_gc_enter_1 ();

}

There’s a bit of metadata given at the top of the function, this is a description of the info table that will be stored next to the actual code for this function. You can look at CmmInfoTable in cmm/CmmDecl.hs if you’re interested in what the values mean; most notably the tag 17 corresponds to THUNK_1_0: this is a thunk that has in its environment (the free variables: in this case wild_sgC) a single pointer and no non-pointers.

Without attempting to understand the code, we can see a few interesting things: we are jumping to base_GHCziNum_zm_info, which is a Z-encoded name for base GHC.Num - info: hey, that’s our subtraction function! In that case, a reasonable guess is that the values we are writing to the stack are the arguments for this function. Let’s pull up the STG invocation again: GHC.Num.- GHC.Num.$fNumInt wild_sgC sat_sgH (recall sat_sgH was a constant 1).base_GHCziNum_zdfNumInt_closureis Z-encodedbase GHC.Num $fNumInt, so there is our dictionary function.stg_INTLIKE_closure+137is a rather curious constant, which happens to point to a statically allocated closure representing the number1. Which means at last we haveI32[R1 + 8], which must refer towild_sgC(in factR1is a pointer to this thunk’s closure on the stack.) You may ask, what dostg_ap_pp_infoandstg_upd_frame_infodo, and why isbase_GHCziNum_zdfNumInt_closureat the very bottom of the stack? The key is to realize that in fact, we’re placing three distinct entities on the stack: an argument forbase_GHCziNum_zm_info, astg_ap_pp_infoobject with a closure containingI32[R1 + 8]andstg_INTLIKE_closure+137, and astg_upd_frame_infoobject with a closure containingR1. We’ve delicately setup a Rube Goldberg machine, that when run, will do the following things: 1. Insidebase_GHCziNum_zm_info, consume the argumentbase_GHCziNum_zdfNumInt_closureand figure out what the right subtraction function for this dictionary is, put this function on the stack, and then jump to its return point, the next info table on the stack,stg_ap_pp_info. 2. Insidestg_ap_pp_info, consume the argument thatbase_GHCziNum_zm_infocreated, and apply it with the two argumentsI32[R1 + 8]andstg_INTLIKE_closure+137. (As you might imagine,stg_ap_pp_infois very simple.) 3. The subtraction function runs and does the actual subtraction. It then invokes the next info table on the stackstg_upd_frame_infowith this argument. 4. Because this is an updateable closure (remember theucharacter in STG?), willstg_upd_frame_infothe result of step 3 and use it to overwrite the closure pointed to byR1(the original closure of the thunk) with a new closure that simply contains the new value. It will then invoke the next info table on the stack, which was whatever was on the stack when we enteredsgI_Entry. Phew! And now there’s the minor question ofif (Sp - 24 < SpLim) goto ch2;which checks if we will overflow the stack and bugs out to the garbage collector if so.sgJ_entrydoes something very similar, but this time the continuation chain isFactorial_facttostg_upd_frame_infoto the great beyond. We also need to allocate a new closure on the heap (sgI_info), which will be passed in as an argument:: sgJ_entry() { has static closure: False update_frame: <none> type: 0 desc: 0 tag: 17 ptrs: 1 nptrs: 0 srt: (Factorial_fact_srt,0,3) } ch5: if (Sp - 12 < SpLim) goto ch7; Hp = Hp + 12; if (Hp > HpLim) goto ch7; I32[Sp - 8] = stg_upd_frame_info; I32[Sp - 4] = R1; I32[Hp - 8] = sgI_info; I32[Hp + 0] = I32[R1 + 8]; I32[Sp - 12] = Hp - 8; Sp = Sp - 12; jump Factorial_fact_info (); ch7: HpAlloc = 12; jump stg_gc_enter_1 (); } And finally,sgC_retactually does computation:: sgC_ret() { has static closure: False update_frame: <none> type: 0 desc: 0 tag: 34 stack: [] srt: (Factorial_fact_srt,0,3) } ch9: Hp = Hp + 12; if (Hp > HpLim) goto chb; _sgG::I32 = I32[R1 + 3]; if (_sgG::I32 != 0) goto chd; R1 = stg_INTLIKE_closure+137; Sp = Sp + 4; Hp = Hp - 12; jump (I32[Sp + 0]) (); chb: HpAlloc = 12; jump stg_gc_enter_1 (); chd: I32[Hp - 8] = sgJ_info; I32[Hp + 0] = R1; I32[Sp + 0] = Hp - 8; I32[Sp - 4] = R1; I32[Sp - 8] = stg_ap_pp_info; I32[Sp - 12] = base_GHCziNum_zdfNumInt_closure; Sp = Sp - 12; jump base_GHCziNum_zt_info (); } ...though not very much of it. We grab the result of the case split fromI32[R1 + 3](R1 is a tagged pointer, which is why the offset looks weird.) We then check if its zero, and if it is we shovestg_INTLIKE_closure+137(the literal 1) into our register and jump to our continuation; otherwise we setup our arguments on the stack to do a multiplicationbase_GHCziNum_zt_info. The same dictionary passing dance happens. And that’s it! While we’re here, here is a brief shout-out to “Optimised Cmm”, which is just Cmm but with some minor optimisations applied to it. If you’re *really* interested in the correspondence to the underlying assembly, this is good to look at. :: ghc -c Factorial.hs -ddump-opt-cmm Assembly ------------ :: ghc -c Factorial.hs -ddump-asm Finally, we get to assembly. It’s mostly the same as the Cmm, minus some optimizations, instruction selection and register allocation. In particular, all of the names from Cmm are preserved, which is useful if you’re debugging compiled Haskell code with GDB and don’t feel like wading through assembly: you can peek at the Cmm to get an idea for what the function is doing. Here is one excerpt, which displays some more salient aspects of Haskell on x86-32:: sgK_info: .Lch9: leal -24(%ebp),%eax cmpl 84(%ebx),%eax jb .Lchb movl $stg_upd_frame_info,-8(%ebp) movl %esi,-4(%ebp) movl $stg_INTLIKE_closure+137,-12(%ebp) movl 8(%esi),%eax movl %eax,-16(%ebp) movl $stg_ap_pp_info,-20(%ebp) movl $base_GHCziNum_zdfNumInt_closure,-24(%ebp) addl $-24,%ebp jmp base_GHCziNum_zm_info .Lchb: jmp *-8(%ebx) Some of the registers are pinned to registers we saw in Cmm. The first two lines are the stack check, and we can see that%ebpis always set to the value ofSp.84(%ebx)must be whereSpLim; indeed,%ebxstores a pointer to theBaseRegstructure, where we store various “register-like” data as the program executes (as well as the garbage collection function, see*-8(%ebx)). Afterwards, a lot of code moves values onto the stack, and we can see that%esicorresponds toR1. In fact, once you’ve allocated all of these registers, there aren’t very many general purpose registers to actually do computation in: just%eaxand%edx. Conclusion ------------- That’s it: factorial all the way down to the assembly level! You may be thinking several things: * *Holy crap! The next time I need to enter an obfuscated C contest, I’ll just have GHC generate my code for me.* GHC’s internal operational model is indeed very different from any imperative language you may have seen, but it is very regular, and once you get the hang of it, rather easy to understand. * *Holy crap! I can’t believe that Haskell performs at all!* Remember we didn’t compile with optimizations at all. The same module compiled with-O`` is considerably smarter.

Thanks for reading all the way! Stay tuned for the near future, where I illustrate action on the Haskell heap in comic book format.

April 11, 2011I was supposed to have another post about Hoopl today, but it got scuttled when an example program I had written triggered what I think is a bug in Hoopl (if it’s not a bug, then my mental model of how Hoopl works internally is seriously wrong, and I ought not write about it anyway.) So today’s post will be about the alleged bug Hoopl was a victim of: bugs from using the wrong variable.

The wrong variable, if I’m right, is that of the missing apostrophe:

; let (cha', fbase') = mapFoldWithKey

- (updateFact lat lbls)

+ (updateFact lat lbls')

(cha,fbase) out_facts

Actually, this bug tends to happen a lot in functional code. Here is one bug in the native code generation backend in GHC that I recently fixed with Simon Marlow:

- return (Fixed sz (getRegisterReg use_sse2 reg) nilOL)

+ return (Fixed size (getRegisterReg use_sse2 reg) nilOL)

And a while back, when I was working on abcBridge, I got an infinite loop because of something along the lines of:

cecManVerify :: Gia_Man_t -> Cec_ParCec_t_ -> IO Int

- cecManVerify a b = handleAbcError "Cec_ManVerify" $ cecManVerify a b

+ cecManVerify a b = handleAbcError "Cec_ManVerify" $ cecManVerify' a b

How does one defend against these bugs? There are various choices:

This is the classic solution for any imperative programmer: if some value is not going to be used again, overwrite it with the new value. You thus get code like this:

$string = trim($string);

$string = str_replace('/', '_', $string);

$string = ...

You can do something similar in spirit in functional programming languages by reusing the name for a new binding, which shadows the old binding. But this is something of a discouraged practice, as -Wall might suggest:

test.hs:1:24:

Warning: This binding for `a' shadows the existing binding

bound at test.hs:1:11

In the particular case that the variable is used in only one place, in this pipeline style, it’s fairly straightforward to eliminate it by writing a pipeline of functions, moving the code to point-free style (the “point” in “point-free” is the name for variable):

let z = clipJ a . clipI b . extendIJ $ getIJ (q ! (i-1) ! (j-1))

But this tends to work less well when an intermediate value needs to be used multiple times. There’s usually a way to arrange it, but “multiple uses” is a fairly good indicator of when pointfree style will become incomprehensible.

View patterns are a pretty neat language extension that allow you to avoid having to write code that looks like this:

f x y = let x' = unpack x

in ... -- using only x'

With {-# LANGUAGE ViewPatterns #-}, you can instead write:

f (unpack -> x) y = ... -- use x as if it were x'

Thus avoiding the need to create a temporary name that may be accidentally used, while allowing yourself to use names.

It only took a few seconds of staring to see what was wrong with this code:

getRegister (CmmReg reg)

= do use_sse2 <- sse2Enabled

let

sz = cmmTypeSize (cmmRegType reg)

size | not use_sse2 && isFloatSize sz = FF80

| otherwise = sz

--

return (Fixed sz (getRegisterReg use_sse2 reg) nilOL)

That’s right: size is never used in the function body. GHC will warn you about that:

test.hs:1:24: Warning: Defined but not used: `b'

Unfortunately, someone turned it off (glare):

{-# OPTIONS -w #-}

-- The above warning supression flag is a temporary kludge.

-- While working on this module you are encouraged to remove it and fix

-- any warnings in the module. See

-- http://hackage.haskell.org/trac/ghc/wiki/Commentary/CodingStyle#Warnings

-- for details

Haskell programmers tend to have a penchant for short, mathematical style names like f, g, h, x, y, z, when the scope a variable is used isn’t very large. Imperative programmers tend to find this a bit strange and unmaintainable. The reason why this is a maintainable style in Haskell is the static type system: if I’m writing the function compose f g, where f :: a -> b and g :: b -> c, I’m certain not to accidentally use g in the place of f: it will type error! If all of the semantic information about what is in the variable is wrapped up in the type, there doesn’t seem to be much point in reiterating it. Of course, it’s good not to go too far in this direction: the typechecker won’t help you much when there are two variables, both with the type Int. In that case, it’s probably better to use a teensy bit more description. Conversely, if you refine your types so that the two variables have different types again, the possibility of error goes away again.

April 8, 2011Once you’ve determined what dataflow facts you will be collecting, the next step is to write the transfer function that actually performs this analysis for you!

Remember what your dataflow facts mean, and this step should be relatively easy: writing a transfer function usually involves going through every possible statement in your language and thinking about how it changes your state. We’ll walk through the transfer functions for constant propagation and liveness analysis.

Here is the transfer function for liveness analysis (once again, in Live.hs):

liveness :: BwdTransfer Insn Live

liveness = mkBTransfer live

where

live :: Insn e x -> Fact x Live -> Live

live (Label _) f = f

live n@(Assign x _) f = addUses (S.delete x f) n

live n@(Store _ _) f = addUses f n

live n@(Branch l) f = addUses (fact f l) n

live n@(Cond _ tl fl) f = addUses (fact f tl `S.union` fact f fl) n

live n@(Call vs _ _ l) f = addUses (fact f l `S.difference` S.fromList vs) n

live n@(Return _) _ = addUses (fact_bot liveLattice) n

fact :: FactBase (S.Set Var) -> Label -> Live

fact f l = fromMaybe S.empty $ lookupFact l f

addUses :: S.Set Var -> Insn e x -> Live

addUses = fold_EN (fold_EE addVar)

addVar s (Var v) = S.insert v s

addVar s _ = s

live is the meat of our transfer function: it takes an instruction and the current fact, and then modifies the fact in light of that information. Because this is a backwards transfer (BwdTransfer), the Fact x Live passed to live are the dataflow facts after this instruction, and our job is to calculate what the dataflow facts are before the instruction (the facts flow backwards).

If you look closely at this function, there’s something rather curious going on: in the line live (Label _) f = f, we simply pass out f (which ostensibly has type Fact x Live) as the result. How does that work? Well, Fact is actually a type family:

type family Fact x f :: *

type instance Fact C f = FactBase f

type instance Fact O f = f

Look, it’s the O and C phantom types again! If we recall our definition of Insn (in IR.hs):

data Insn e x where

Label :: Label -> Insn C O

Assign :: Var -> Expr -> Insn O O

Store :: Expr -> Expr -> Insn O O

Branch :: Label -> Insn O C

Cond :: Expr -> Label -> Label -> Insn O C

Call :: [Var] -> String -> [Expr] -> Label -> Insn O C

Return :: [Expr] -> Insn O C

That means for any of the instructions that are open on exit (x = O for Label, Assign and Store), our function gets Live, whereas for an instruction that is closed on exit (x = C for Branch, Cond, Call and Return), we get FactBase Live, which is a map of labels to facts (LabelMap Live)—for reasons we will get to in a second.

Because the type of our arguments actually change depending on what instruction we receive, some people (GHC developers among them) prefer to use the long form mkBTransfer3, which takes three functions, one for each shape of node. The rewritten code thus looks like this:

liveness' :: BwdTransfer Insn Live

liveness' = mkBTransfer3 firstLive middleLive lastLive

where

firstLive :: Insn C O -> Live -> Live

firstLive (Label _) f = f

middleLive :: Insn O O -> Live -> Live

middleLive n@(Assign x _) f = addUses (S.delete x f) n

middleLive n@(Store _ _) f = addUses f n

lastLive :: Insn O C -> FactBase Live -> Live

lastLive n@(Branch l) f = addUses (fact f l) n

lastLive n@(Cond _ tl fl) f = addUses (fact f tl `S.union` fact f fl) n

lastLive n@(Call vs _ _ l) f = addUses (fact f l `S.difference` S.fromList vs) n

lastLive n@(Return _) _ = addUses (fact_bot liveLattice) n

(with the same definitions for fact, addUses and addVar).

With this in mind, it should be fairly easy to parse the code for firstLive and middleLive. Labels don’t change the set of live libraries, so our fact f is passed through unchanged. For assignments and stores, any uses of a register in that expression makes that register live (addUses is a utility function that calculates this), but if we assign to a register, we lose its previous value, so it is no longer live. Here is some pseudocode demonstrating:

// a is live

x = a;

// a is not live

foo();

// a is not live

a = 2;

// a is live

y = a;

If you’re curious out the implementation of addUses, the fold_EE and fold_EN functions can be found in OptSupport.hs:

fold_EE :: (a -> Expr -> a) -> a -> Expr -> a

fold_EN :: (a -> Expr -> a) -> a -> Insn e x -> a

fold_EE f z e@(Lit _) = f z e

fold_EE f z e@(Var _) = f z e

fold_EE f z e@(Load addr) = f (f z addr) e

fold_EE f z e@(Binop _ e1 e2) = f (f (f z e2) e1) e

fold_EN _ z (Label _) = z

fold_EN f z (Assign _ e) = f z e

fold_EN f z (Store addr e) = f (f z e) addr

fold_EN _ z (Branch _) = z

fold_EN f z (Cond e _ _) = f z e

fold_EN f z (Call _ _ es _) = foldl f z es

fold_EN f z (Return es) = foldl f z es

The naming convention is as follows: E represents an Expr, while N represents a Node (Insn). The left letter indicates what kind of values are passed to the combining function, while the right letter indicates what is being folded over. So fold_EN folds all Expr in a Node and calls the combining function on it, while fold_EE folds all of the Expr inside an Expr (notice that things like Load and Binop can contain expressions inside themselves!) The effect of fold_EN (fold_EE f), then, is that f will be called on every expression in a node, which is exactly what we want if we’re checking for uses of Var.

We could have also written out the recursion explicitly:

addUses :: S.Set Var -> Insn e x -> Live

addUses s (Assign _ e) = expr s e

addUses s (Store e1 e2) = expr (expr s e1) e2

addUses s (Cond e _ _) = expr s e

addUses s (Call _ _ es _) = foldl expr s es

addUses s (Return es) = foldl expr s es

addUses s _ = s

expr :: S.Set Var -> Expr -> Live

expr s e@(Load e') = addVar (addVar s e) e'

expr s e@(Binop _ e1 e2) = addVar (addVar (addVar s e) e1) e2

expr s e = addVar s e

But as you can see, there’s a lot of junk involved with recursing down the structure, and you might accidentally forget an Expr somewhere, so using a pre-defined fold operator is preferred. Still, if you’re not comfortable with folds over complicated datatypes, writing out the entire thing in full at least once is a good exercise.

The last part to look at is lastLives:

lastLive :: Insn O C -> FactBase Live -> Live

lastLive n@(Branch l) f = addUses (fact f l) n

lastLive n@(Cond _ tl fl) f = addUses (fact f tl `S.union` fact f fl) n

lastLive n@(Call vs _ _ l) f = addUses (fact f l `S.difference` S.fromList vs) n

lastLive n@(Return _) _ = addUses (fact_bot liveLattice) n

There are several questions to ask.

Why does it receive a FactBase Live instead of a Live? This is because, as the end node in a backwards analysis, we may receive facts from multiple locations: each of the possible paths the control flow may go down.

In the case of a Return, there are no further paths, so we use fact_bot liveLattice (no live variables). In the case of Branch and Call, there is only one further path l (the label we’re branching or returning to), so we simply invoke fact f l. And finaly, for Cond there are two paths: tl and fl, so we have to grab the facts for both of them and combine them with what happens to be our join operation on the dataflow lattice.

Why do we still need to call addUses? Because instructions at the end of basic blocks can use variables (Cond may use them in its conditional statement, Return may use them when specifying what it returns, etc.)

What’s with the call to S.difference in Call? Recall that vs is the list of variables that the function call writes its return results to. So we need to remove those variables from the live variable set, since they will get overwritten by this instruction:

f (x, y) {

L100:

goto L101

L101:

if x > 0 then goto L102 else goto L104

L102:

// z is not live here

(z) = f(x-1, y-1) goto L103

L103:

// z is live here

y = y + z

x = x - 1

goto L101

L104:

ret (y)

}

You should already have figured out what fact does: it looks up the set of dataflow facts associated with a label, and returns an empty set (no live variables) if that label isn’t in our map yet.

Once you’ve seen one Hoopl analysis, you’ve seen them all! The transfer function for constant propagation looks very similar:

-- Only interesting semantic choice: values of variables are live across

-- a call site.

-- Note that we don't need a case for x := y, where y holds a constant.

-- We can write the simplest solution and rely on the interleaved optimization.

--------------------------------------------------

-- Analysis: variable equals a literal constant

varHasLit :: FwdTransfer Node ConstFact

varHasLit = mkFTransfer ft

where

ft :: Node e x -> ConstFact -> Fact x ConstFact

ft (Label _) f = f

ft (Assign x (Lit k)) f = Map.insert x (PElem k) f

ft (Assign x _) f = Map.insert x Top f

ft (Store _ _) f = f

ft (Branch l) f = mapSingleton l f

ft (Cond (Var x) tl fl) f

= mkFactBase constLattice

[(tl, Map.insert x (PElem (Bool True)) f),

(fl, Map.insert x (PElem (Bool False)) f)]

ft (Cond _ tl fl) f

= mkFactBase constLattice [(tl, f), (fl, f)]

ft (Call vs _ _ bid) f = mapSingleton bid (foldl toTop f vs)

where toTop f v = Map.insert v Top f

ft (Return _) _ = mapEmpty

The notable difference is that, unlike liveness analysis, constant propagation analysis is a forward analysis FwdTransfer. This also means the type of the function is Node e x -> f -> Fact x f, rather than Node e x -> Fact x f -> f: when the control flow splits, we can give different sets of facts for the possible outgoing labels. This is used to good effect in Cond (Var x), where we know that if we take the first branch the condition variable is true, and vice-versa. The rest is plumbing:

Branch: An unconditional branch doesn’t cause any of our variables to stop being constant. Hoopl will automatically notice if a different path to that label has contradictory facts and convert the mappings to Top as notice, using our lattice’s join function. mapSingleton creates a singleton map from the label l to the fact f.Cond: We need to create a map with two entries, which is can be done conveniently with mkFactBase, where the last argument is a list of labels to maps.Call: A function call is equivalent to assigning lots of unknown variables to all of its return variables, so we set all of them to unknown with toTop.Return: Goes nowhere, so an empty map will do.

Next time, we’ll talk about some of the finer subtleties about transfer functions and join functions, and discuss graph rewriting, and wrap it all up with some use of Hoopl’s debugging facilities to observe how Hoopl rewrites a graph.

April 5, 2011The imperative. When should you create a custom data type, as opposed to reusing pre-existing data types such as Either, Maybe or tuples? Here are some reasons you should reuse a generic type:

- It saves typing (both in declaration and in pattern matching), making it good for one-off affairs,

- It gives you a library of predefined functions that work with that type,

- Other developers have expectations about what the type does that make understanding quicker.

On the flip side of the coin:

- You may lose semantic distinction between types that are the same but have different meanings (the newtype argument),

- The existing type may allow more values than you intended to allow,

- Other developers have expectations about what the type does that can cause problems if you mean something different.

In this post, I’d like to talk about those last two problems with reusing custom types, using two case studies from the GHC codebase, and how the problems where alleviated by defining a data type that was only used by a small section of the codebase.

Great expectations. The Maybe type, by itself, has a very straight-forward interpretation: you either have the value, or you don’t. Even when Nothing means something like Wildcard or Null or UseTheDefault, the meaning is usually fairly clear.

What is more interesting, however, is when Maybe is placed in another data type that has its own conception of nothing-ness. A very simple example is Maybe (Maybe a), which admits the values Nothing, Just Nothing or Just (Just a). What is Just Nothing supposed to mean? In this case, what we really have masquerading here is a case of a data type with three constructors: data Maybe2 a = Nothing1 | Nothing2 | Just a. If we intend to distinguish between Nothing and Just Nothing, we need to assign some different semantic meaning to them, meaning that is not obvious from the cobbled together data type.

Another example, which comes from Hoopl and GHC, is the curious case of Map Var (Maybe Lit). A map already has its own conception of nothingness: that is, when the key-value pair is not in the map at all! So the first thing a developer who encounters this code may ask is, “Why isn’t it just Map Var Lit?” The answer to this question, for those of you have read the dataflow lattice post, is that Nothing in this circumstance, represents top (there is variable is definitely not constant), which is different from absence in the map, which represents bottom (the variable is constant or not constant). I managed to confuse both the Simons with this strange piece of code, and after taking some time to explain the situation, and they immediately recommended that I make a custom data type for the purpose. Even better, I found that Hoopl already provided this very type: HasTop, which also had a number of utility functions that reflected this set of semantics. Fortuitous indeed!

Uninvited guests. Our example of a data type that allows too many values comes from the linear register allocator in GHC (compiler/nativeGen/RegAlloc/Linear/Main.hs). Don’t worry, you don’t need to know how to implement a linear register allocator to follow along.

The linear register allocator is a rather large and unwieldy beast. Here is the function that actually allocates and spills the registers:

allocateRegsAndSpill reading keep spills alloc (r:rs)

= do assig <- getAssigR

case lookupUFM assig r of

-- case (1a): already in a register

Just (InReg my_reg) ->

allocateRegsAndSpill reading keep spills (my_reg:alloc) rs

-- case (1b): already in a register (and memory)

-- NB1. if we're writing this register, update its assignment to be

-- InReg, because the memory value is no longer valid.

-- NB2. This is why we must process written registers here, even if they

-- are also read by the same instruction.

Just (InBoth my_reg _)

-> do when (not reading) (setAssigR (addToUFM assig r (InReg my_reg)))

allocateRegsAndSpill reading keep spills (my_reg:alloc) rs

-- Not already in a register, so we need to find a free one...

loc -> allocRegsAndSpill_spill reading keep spills alloc r rs loc assig

There’s a bit of noise here, but the important things to notice is that it’s a mostly recursive function. The first two cases of lookupUFM directly call allocateRegsAndSpill, but the last case needs to do something complicated, and calls the helper function allocRegsAndSpill_spill. It turns out that this function will always eventually call allocateRegsAndSpill, so we have two mutually recursive functions. The original was probably just recursive, but the long bit handling “Not already in a register, so we need to find a free one” got factored out at some point.

This code is reusing a data type! Can you see it? It’s very subtle, because the original use of the type is legitimate, but it is then reused in an inappropriate manner. The answer is loc, in the last case statement. In particular, because we’ve already case-matched on loc, we know that it can’t possibly be Just (InReg{}) or Just (InBoth{}). If we look at the declaration of Loc, we see that there are only two cases left:

data Loc

-- | vreg is in a register

= InReg !RealReg

-- | vreg is held in a stack slot

| InMem {-# UNPACK #-} !StackSlot

-- | vreg is held in both a register and a stack slot

| InBoth !RealReg

{-# UNPACK #-} !StackSlot

deriving (Eq, Show, Ord)

That is, the only remaining cases are Just (InMem{}) and Nothing. This is fairly important, because we lean on this invariant later in allocRegsAndSpill_spill:

let new_loc

-- if the tmp was in a slot, then now its in a reg as well

| Just (InMem slot) <- loc

, reading

= InBoth my_reg slot

-- tmp has been loaded into a reg

| otherwise

= InReg my_reg

If you hadn’t seen the original case split in allocateRegsAndSpill, this particular code may have got you wondering if the last guard also applied when the result was Just (InReg{}), in which case the behavior would be very wrong. In fact, if we are reading, loc must be Nothing in that last branch. But there’s no way of saying that as the code stands: you’d have to add some panics and it gets quite messy:

let new_loc

-- if the tmp was in a slot, then now its in a reg as well

| Just (InMem slot) <- loc

= if reading then InBoth my_reg slot else InReg my_reg

-- tmp has been loaded into a reg

| Nothing <- loc

= InReg my_reg

| otherwise = panic "Impossible situation!"

Furthermore, we notice a really interesting extra invariant: what happens if we’re reading from a location that has never been assigned to before (that is, reading is True and loc is Nothing)? That is obviously bogus, so in fact we should check if that’s the case. Notice that the original code did not enforce this invariant, which was masked out by the use of otherwise.

Rather than panic on an impossible situation, we should statically rule out this possibility. We can do this simply by introducing a new data type for loc, and pattern-matching appropriately:

-- Why are we performing a spill?

data SpillLoc = ReadMem StackSlot -- reading from register only in memory

| WriteNew -- writing to a new variable

| WriteMem -- writing to register only in memory

-- Note that ReadNew is not valid, since you don't want to be reading

-- from an uninitialized register. We also don't need the location of

-- the register in memory, since that will be invalidated by the write.

-- Technically, we could coalesce WriteNew and WriteMem into a single

-- entry as well. -- EZY

allocateRegsAndSpill reading keep spills alloc (r:rs)

= do assig <- getAssigR

let doSpill = allocRegsAndSpill_spill reading keep spills alloc r rs assig

case lookupUFM assig r of

-- case (1a): already in a register

Just (InReg my_reg) ->

allocateRegsAndSpill reading keep spills (my_reg:alloc) rs

-- case (1b): already in a register (and memory)

-- NB1. if we're writing this register, update its assignment to be

-- InReg, because the memory value is no longer valid.

-- NB2. This is why we must process written registers here, even if they

-- are also read by the same instruction.

Just (InBoth my_reg _)

-> do when (not reading) (setAssigR (addToUFM assig r (InReg my_reg)))

allocateRegsAndSpill reading keep spills (my_reg:alloc) rs

-- Not already in a register, so we need to find a free one...

Just (InMem slot) | reading -> doSpill (ReadMem slot)

| otherwise -> doSpill WriteMem

Nothing | reading -> pprPanic "allocateRegsAndSpill: Cannot read from uninitialized register" (ppr r)

| otherwise -> doSpill WriteNew

And now the pattern match inside allocateRegsAndSpill_spill is nice and tidy:

-- | Calculate a new location after a register has been loaded.

newLocation :: SpillLoc -> RealReg -> Loc

-- if the tmp was read from a slot, then now its in a reg as well

newLocation (ReadMem slot) my_reg = InBoth my_reg slot

-- writes will always result in only the register being available

newLocation _ my_reg = InReg my_reg

April 4, 2011The essence of dataflow optimization is analysis and transformation, and it should come as no surprise that once you’ve defined your intermediate representation, the majority of your work with Hoopl will involve defining analysis and transformations on your graph of basic blocks. Analysis itself can be further divided into the specification of the dataflow facts that we are computing, and how we derive these dataflow facts during analysis. In part 2 of this series on Hoopl, we look at the fundamental structure backing analysis: the dataflow lattice. We discuss the theoretical reasons behind using a lattice and give examples of lattices you may define for optimizations such as constant propagation and liveness analysis.

Despite its complicated sounding name, dataflow analysis remarkably resembles the way human programmers might reason about code without actually running it on a computer. We start off with some initial belief about the state of the system, and then as we step through instructions we update our belief with new information. For example, if I have the following code:

f(x) {

a = 3;

b = 4;

return (x * a + b);

}

At the very top of the function, I don’t know anything about x. When I see the expressions a = 3 and b = 4, I know that a is equal to 3 and b is equal to 4. In the least expression, I could use constant propagation to simplify the result to x * 3 + 4. Indeed, in the absence of control flow, we can think of analysis simply as stepping through the code line by line and updating our assumptions, also called dataflow facts. We can do this in both directions: the analysis we just did above was forwards analysis, but we can also do backwards analysis, which is the case for liveness analysis.

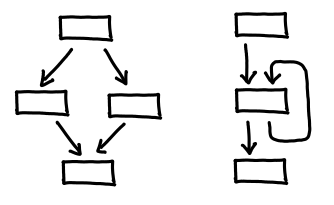

Alas, if only things were this simple! There are two spanners in the works here: Y-shaped control flows and looping control flows.

Y-shaped control flows (called joins, for both obvious reasons and reasons that will become clear soon) are so named because there are two, distinct paths of execution that then merge into one. We then have two beliefs about the state of the program, which we need to reconcile before carrying on:

f(x) {

if (x) {

a = 2; // branch A

} else {

a = 3; // branch B

}

return a;

}

Inside branch A, we know that a is 2, and inside branch B, we know a is 3, but outside this conditional, all we can say is that a is either 2 or 3. (Since two possible values isn’t very useful for constant propagation, we’ll instead say the value of a is top: there is no one value that represents the value held at a.) The upshot is that any set of dataflow facts you are doing analysis with must have a join operation defined:

data DataflowFactsTry1 a = DF1 { fact_join :: a -> a -> a }

There is an analogous situation for backwards analysis, which occurs when you have a conditional jump: two “futures” of the control flow join back together, and so a similar join needs to occur.

Looping control flows also have joins, but they have the further problem that we don’t know what one of the incoming code path’s state is: we can’t figure it out until we’ve analyzed the loop body, but to analyze the loop body, we need to know what the incoming state is. It’s a Catch-22! The trick to work around this is to define a bottom fact, which intuitively represents the most conservative dataflow fact possible: it is the identity when joined some other dataflow fact. So when we encounter one of these loop edges, instead of attempting to calculate the edge (which is a Catch-22 problem), we instead feed in the bottom element, and get an approximation of what the fact at that loop edge is. If this approximation is better than bottom, we feed the new result in instead, and the process repeats until there are no more changes: a fixpoint has been achieved.

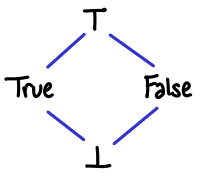

With join and bottom in hand, the mathematically inclined may notice that what we’ve defined looks a lot like a lattice:

data DataflowLattice a = DataflowLattice

{ fact_name :: String -- Documentation

, fact_bot :: a -- Lattice bottom element

, fact_join :: JoinFun a -- Lattice join plus change flag

-- (changes iff result > old fact)

}

type JoinFun a = Label -> OldFact a -> NewFact a -> (ChangeFlag, a)

There is a little bit of extra noise in here: Label is included strictly for debugging purposes (it tells the join function what label the join is occurring on) and ChangeFlag is included for optimization purposes: it lets fact_join efficiently say when the fixpoint has been achieved: NoChange.

Aside: Lattices. Here, we review some basic terminology and intuition for lattices. A lattice is a partially ordered set, for which least upper bounds (lub) and greatest lower bounds (glb) exist for all pairs of elements. If one imagines a Hasse diagram, the existence of a least upper bound means that I can follow the diagram upwards from two elements until I reach a shared element; the greatest least bound is the same process downwards. The least upper bound is also called the join of two elements, and the greatest least bound the meet. (I prefer lub and glb because I always mix join and meet up!) Notationally, the least upper bound is represented with the logical or symbol or a square union operator, while the greatest least bound is represented with the logical and symbol or square intersection operator. The choice of symbols is suggestive: the overloading of logical symbols corresponds to the fact that logical propositions can have their semantics defined using a special kind of lattice called a boolean algebra, where lub is equivalent to or and glb is equivalent to and (bottom is falsity and top is tautology). The overloading of set operators corresponds to the lattice on the usual ordering of the powerset construction: lub is set union and glb is set intersection.

In Hoopl, we deal with bounded lattices, lattices for which a top and bottom element exist. These are special elements that are greater than and less than (respectively) than all other elements. Joining the bottom element with any other element is a no-op: the other element is the result (this is why we use bottom as our initialization value!) Joining the top element with any other element results in the top element (thus, if you get to the top, you’re “stuck”, so to speak).

For the pedantic, strictly speaking, Hoopl doesn’t need a lattice: instead, we need a bounded semilattice (since we only require joins, and not meets, to be defined.) There is another infelicity: the Lerner-Grove-Chambers and Hoopl uses bottom and join, but most of the existing literature on dataflow lattices uses top and meet (essentially, flip the lattice upside down.) In fact, which choice is “natural” depends on the analysis: as we will see, liveness analysis naturally suggests using bottom and join, while constant propagation suggests using top and meet. To be consistent with Hoopl, we’ll use bottom and join consistently; as long as we’re consistent, the lattice orientation doesn’t matter.

We will now look at concrete examples of using the dataflow lattices for liveness analysis and constant propagation. These two examples give a nice spread of lattices to look at: liveness analysis is a set of variable names, while constant propagation is a map of variable names to a flat lattice of possible values.

Liveness analysis (Live.hs) uses a very simple lattice, so it serves as a good introductory example for the extra ceremony that is involved in setting up a DataflowLattice:

type Live = S.Set Var

liveLattice :: DataflowLattice Live

liveLattice = DataflowLattice

{ fact_name = "Live variables"

, fact_bot = S.empty

, fact_join = add

}

where add _ (OldFact old) (NewFact new) = (ch, j)

where

j = new `S.union` old

ch = changeIf (S.size j > S.size old)

The type Live is the type of our data flow facts. This represents is the set of variables that are live (that is, will be used by later code):

f() {

// live: {x, y}

x = 3;

y = 4;

y = x + 2;

// live: {y}

return y;

// live: {}

}

Remember that liveness analysis is a backwards analysis: we start at the bottom of our procedure and work our way up: a usage of a variable means that it’s live for all points above it. We fill in DataflowLattice with documentation, the distinguished element (bottom) and the operation on these facts (join). Var is Expr.hs and simply is a string name of the variable. Our bottom element (which is used to initialize edges that we can’t calculate right off the bat) is the empty set, since at the bottom of any procedure, all variables are dead.

Join is set union, which can be clearly seen in this example:

f (x) {

// live: {a,b,x,r} (union of the two branches,

// as well as x, due to its usage in the conditional)

a = 2;

b = 3;

if (x) {

// live: {a,r}

r = a;

} else {

// live: {b,r}

r = b;

}

// live: {r}

return r;

// live: {}

}

We also see some code for calculating the change ch, which is a simple size comparison of sets, because union will only ever increase the size of a set, not decrease it. changeIf is a utility function that takes Bool to ChangeFlag.

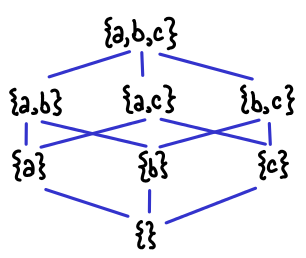

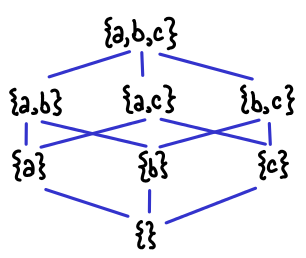

Here is an illustration of the lattice structure if we have three variables: it’s simply the usual ordering on the powerset construction.

Here is the lattice for constant propagation (ConstProp.hs). It is slightly more complicated than the live set, though some of the complexity is hidden by the fact that Hoopl provides some utility data types and functions:

-- ConstFact:

-- Not present in map => bottom

-- PElem v => variable has value v

-- Top => variable's value is not constant

type ConstFact = Map.Map Var (WithTop Lit)

constLattice :: DataflowLattice ConstFact

constLattice = DataflowLattice

{ fact_name = "Const var value"

, fact_bot = Map.empty

, fact_join = joinMaps (extendJoinDomain constFactAdd) }

where

constFactAdd _ (OldFact old) (NewFact new)

= if new == old then (NoChange, PElem new)

else (SomeChange, Top)

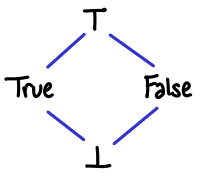

There are essentially two lattices in this construction. The “outer” lattice is the map, for which the bottom element is the empty map and the join is joining two maps together, merging elements using the inner lattice. The “inner” (semi)lattice is WithTop Lit, which is provided by Hoopl. (One may say that the inner lattice is pointwise lifted into the map.) We illustrate the inner lattice here for variables containing booleans:

One thing to stress about the inner lattice is the difference between bottom and top. Both represent a sort of “not knowing about the contents of a variable”, but in the case of bottom, the variable may be constant or it may not be constant, whereas in top, the variable is definitely not constant. It is easy to get tripped up saying things like, “bottom means that we don’t know what the value of the variable is” and “top means that the value of the variable could be anything.” If we think of this lattice as a set, with {True} indicating that the value of this variable is true, then {True,False} (bottom) indicates the variable could be a constant true or constant false, not that the variable could be true or false. This also means we can interpret {} (top) appropriately: there is no value for which this variable is a constant. (Notice that this is the powerset lattice flipped upside down!)

There are a few interesting utility functions in this example: extendJoinDomain and joinMaps. extendJoinDomain saves us the drudgery from having to write out all of the interactions with top in full, e.g.:

constFactAddExtended _ (OldFact old) (NewFact new)

= case (old, new) of

(Top, _) -> (NoChange, Top)

(_, Top) -> (SomeChange, Top)

(PElem old, PElem new) | new == old -> (NoChange, PElem new)

| otherwise -> (SomeChange, Top)

joinMaps lifts our inner lattice into map form, and also takes care of the ChangeFlag plumbing (output SomeChange if any entry in the new map wasn’t present in the old map, or if any of the joined entries changed).

That concludes our discussion of Hoopl and dataflow lattices. We haven’t covered all of the functions Hoopl provides to manipulate dataflow lattices; here are some further modules to look at:

Compiler.Hoopl.Combinators defines pairLattice, which takes the product construction of two lattices. It can be used to easily perform multiple analyses at the same time.Compiler.Hoopl.Pointed defines a number of auxiliary data structures and functions for adding Top and Bottom to existing data types. This is where extendJoinDomain comes from.Compiler.Hoopl.Collections and Compiler.Hoopl.Unique define maps and sets on unique keys (most prominently, labels). You will most probably be using these for your dataflow lattices.

Next time, we will talk about transfer functions, the mechanism by which we calculate dataflow facts.

Further reading. Dataflow lattices are covered in chapter 10.11 of Compilers: Principles, Techniques and Tools (the Red Dragon Book). The original paper was Kildall’s 1973 paper A unified approach to global program optimization. Interestingly enough, the Dragon Book remarks that “it has not seen widespread use, probably because the amount of labor saved by the system is not as great as that saved by tools like parser generators.” My feeling is that this is the case for traditional compiler optimization passes, but not for Lerner-Grove-Chambers style passes (where analysis and rewriting are interleaved.)

April 1, 2011Hoopl is a higher-order optimization library. We think it’s pretty cool! This series of blog post is meant to give a tutorial-like introduction to this library, supplementing the papers and the source code. I hope this series will also have something for people who aren’t interested in writing optimization passes with Hoopl, but are interested in the design of higher-order APIs in Haskell. By the end of this tutorial, you will be able to understand references in code to names such as analyzeAndRewriteFwd and DataflowLattice, and make decode such type signatures as:

analyzeAndRewriteFwd

:: forall m n f e x entries. (CheckpointMonad m, NonLocal n, LabelsPtr entries)

=> FwdPass m n f

-> MaybeC e entries

-> Graph n e x -> Fact e f

-> m (Graph n e x, FactBase f, MaybeO x f)

We assume basic familiarity with functional programming and compiler technology, but I will give asides to introduce appropriate basic concepts.

Aside: Introduction. People already familiar with the subject being discussed can feel free to skip sections that are formatted like this.

We will be giving a guided tour of the testing subdirectory of Hoopl, which contains a sample client. (You can grab a copy by cloning the Git repository git clone git://ghc.cs.tufts.edu/hoopl/hoopl.git). You can get your bearings by checking out the README file. The first set of files we’ll be checking out is the “Base System” which defines the data types for the abstract syntax tree and the Hoopl-fied intermediate representation.

The abstract syntax is about as standard as it gets (Ast.hs):

data Proc = Proc { name :: String, args :: [Var], body :: [Block] }

data Block = Block { first :: Lbl, mids :: [Insn], last :: Control }

data Insn = Assign Var Expr

| Store Expr Expr

data Control = Branch Lbl

| Cond Expr Lbl Lbl

| Call [Var] String [Expr] Lbl

| Return [Expr]

type Lbl = String

We have a language of named procedures, which consist of basic blocks. We support unconditional branches Branch, conditional branches Cond, function calls Call (the [Var] is the variables to store the return values, the String is the name of the function, the [Expr] are the arguments, and the Lbl is where to jump to when the function call is done), and function returns Return (multiple return is supported, thus [Expr] rather than Expr).

We don’t have any higher-level flow control constructs (the language’s idea of control flow is a lot of gotos—don’t worry, this will work in our favor), so we might expect it to be very easy to map this “high-level assembly language” to machine code fairly easily, and this is indeed the case (very notably, however, this language doesn’t require you to think about register allocation, but how we use variables will very noticeably impact register allocation). A real-world example of high-level assembly languages includes C–.

Here is a simple example of some code that might be written in this language:

Aside: Basic blocks. Completely explaining what an abstract syntax tree (AST) is a bit beyond the scope of this post, but you if you know how to write a Scheme interpreter in Haskell you already know most of the idea for the expressions component of the language: things like binary operators and variables (e.g. a + b). We then extend this calculator with low-level imperative features in the obvious way. If you’ve done any imperative programming, most of these features are also familiar (branches, function calls, variable assignments): the single new concept is that of the basic block. A basic block is an atomic unit of flow control: if I’ve entered a basic block, I know that I will emerge out the other end, no ifs, ands or buts. This means that there will be no nonlocal transfer of control from inside the block (e.g. no exceptions), and there will be no code that can jump to a point inside this block (e.g. no goto). Any control flow occurs at the end of the basic block, where we may unconditionally jump to another block, or make a function call, etc. Real programs won’t be written this way, but we easily convert them into this form, and we will want this style of representation because it will make it easier to do dataflow analysis. As such, our example abstract syntax tree doesn’t really resemble an imperative language you would program in, but it is easily something you might target during code generation, so the example abstract-syntax tree is setup in this manner.

Hoopl is abstract over the underlying representation, but unfortunately, we can’t use this AST as it stands; Hoopl has its own graph representation. We wouldn’t want to use our representation anyway: we’ve represented the control flow graph as a list of blocks [Block]. If I wanted to pull out the block for some particular label; I’d have to iterate over the entire list. Rather than invent our own more efficient representation for blocks (something like a map of labels to blocks), Hoopl gives us a representation Graph n e x (it is, after all, going to have to operate on this representation). The n stands for “node”, you supply the data structure that makes up the nodes of the graph, while Hoopl manages the graph itself. The e and the x parameters will be used to store information about what the shape of the node is, and don’t represent any particular data.

Here is our intermediate representation (IR.hs):

data Proc = Proc { name :: String, args :: [Var], entry :: Label, body :: Graph Insn C C }

data Insn e x where

Label :: Label -> Insn C O

Assign :: Var -> Expr -> Insn O O

Store :: Expr -> Expr -> Insn O O

Branch :: Label -> Insn O C

Cond :: Expr -> Label -> Label -> Insn O C

Call :: [Var] -> String -> [Expr] -> Label -> Insn O C

Return :: [Expr] -> Insn O C

The notable differences are:

Proc has Graph Insn C C as its body, rather than [Block]. Also, because Graph has no conception of a “first” block, we have to explicitly say what the entry is with entry.- Instead of using

String as Lbl, we’ve switched to a Hoopl provided Label data type. Insn, Control and Label have all been squashed into a single Insn generalized abstract data type (GADT) that handles all of them.

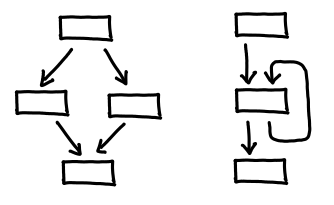

Importantly, however, we’ve maintained the information about what shape the node is via the e and x parameters. e stands for entry, x stands for exit, O stands for open, and C stands for closed. Every instruction has a shape, which you can imagine to be a series of pipes, which you are connecting together. Pipes with the shape C O (closed at the entrance, open at the exit) start the block, pipes with the shape O C (open at the entrance, closed at the exit) end the block, and you can have any number of O O pipes in-between. We can see that Insn C O corresponds to our old data type Ast.Lbl, Insn O O corresponds to Ast.Insn, and Insn O C corresponds to Ast.Control. When we put nodes together, we get graphs, which also can be variously open or closed.

Aside: Generalized Abstract Data Types. GADTs are an indispensable swiss army knife for type-level programming. In this aside, we briefly describe some tricks (ala subtyping) that can be used with Insn e x we gave above.

The first “trick” is that you can ignore the phantom type variable entirely, and use Insn like an ordinary data type:

isLabel :: Insn e x -> Bool

isLabel Label{} = True

isLabel _ = False

I can pass this function a Label and it will return me True, or I can pass it a Branch and it will return me False. Pattern-matching on the GADT does not result in type refinement that I care about in this particular example, because there is no type variable e or x in the fields of any of the constructors or the return type of the function.

Of course, I could have written this function in such a way that it would be impossible to pass something that is not a Label to it:

assertLabel :: Insn C O -> Bool

assertLabel Label{} = True

If you try making a call assertLabel (Branch undefined), you’ll get this nice type error from GHC:

<interactive>:1:13:

Couldn't match expected type `C' against inferred type `O'

Expected type: Insn C O

Inferred type: Insn O C

In the first argument of `assertLabel', namely `(Branch undefined)'

In the expression: assertLabel (Branch undefined)

Let’s unpack this: any constructor Branch will result in a value of type Insn O C. However, the type signature of our function states Insn C O, and C ≠ O. The type error is quite straight-forward, and exactly enough to tell us what’s gone wrong!

Similarly, I can write a different function:

transferMiddle :: Insn O O -> Bool

transferMiddle Assign{} = True

transferMiddle Store{} = False

There’s no type-level way to distinguish between Assign and Store, but I don’t have to provide pattern matches against anything else in the data type: Insn O O means I only need to handle constructors that fit this shape.

I can even partially specify what the allowed shapes are:

transferMiddleOrEnd :: Insn O x -> Bool

For this function, I would need to provide pattern matches against the instructions and the control operators, but not a pattern match for IR.Label. This is not something I could have done easily with the original AST: I would have needed to create a sum type Ast.InsnOrControl.

Quick question. If I have a function that takes Insn e x as an argument, and I’d like to pass this value to a function that only takes Insn C x, what do I have to do? What about the other way around?

Exercise. Suppose you were designing a Graph representation for Hoopl, but you couldn’t use GADTs. What would the difference between a representation Graph IR.Insn (where IR.Insn is just like our IR GADT, but without the phantom types) and a representation Graph Ast.Label Ast.Insn Ast.Control?