May 16, 2011A big thanks to everyone who everyone who sent in space leak specimens. All of the leaks have been inspected and cataloged by our experts, and we are quite pleased to open the doors of the space leak zoo to the public!

There are a few different types of space leak here, but they are quite different and a visitor would do well not to confuse them (the methods for handling them if encountered in the wild vary, and using the wrong technique could exacerbate the situation).

- A memory leak is when a program is unable to release memory back to the operating system. It’s a rare beast, since it has been mostly eliminated by modern garbage collection. We won’t see any examples of it in this series, though it is strictly possible for Haskell programs to exhibit this type of leak if they use non-bracketed low-level FFI allocation functions.

- A strong reference leak is when a program keeps around a reference to memory that in principle could be used but actually will never be used anymore. A confluence of purity and laziness make these types of leaks uncommon in idiomatic Haskell programs. Purity sidesteps these leaks by discouraging the use of mutable references, which can leak memory if they are not cleared when appropriate. Laziness sidesteps these leaks by making it difficult to accidentally generate too much of a data structure when you only want parts of it: we just use less memory to begin with. Of course, using mutable references or strictness in Haskell can reintroduce these errors (sometimes you can fix instances of the former with weak references—thus the name, “strong reference” leak), and live variable leaks (described below) are a type of strong reference leak that catch people unfamiliar with closures by surprise.

- A thunk leak is when a program builds up a lot of unevaluated thunks in memory which intrinsically take up a lot of space. It can be observed when a heap profile shows a large number of

THUNK objects, or when you stack overflow from evaluating a chain of these thunks. These leaks thrive on lazy evaluation, and as such are relatively rare in the imperative world. You can fix them by introducing appropriate strictness. - A live variable leak is when some closure (either a thunk or a lambda) contains a reference to memory that a programmer expects to have been freed already. They arise because references to memory in thunks and functions tend to be implicit (via live variables) as opposed to explicit (as is the case for a data record.) In instances where the result of the function is substantially smaller, these leaks can be fixed by introducing strictness. However, these are not as easy to fix as thunk leaks, as you must ensure all of the references are dropped. Furthermore, the presence of a large chunk of evaluated memory may not necessarily indicate a live variable leak; rather, it may mean that streaming has failed. See below.

- A streaming leak is when a program should only need a small amount of the input to produce a small amount of output, thus using only a small amount of memory, but it doesn’t. Instead, large amounts of the input are forced and kept in memory. These leaks thrive on laziness and intermediate data structures, but, unlike the case of thunk leaks, introducing strictness can exacerbate the situation. You can fix them by duplicating work and carefully tracking data dependencies.

- A stack overflow is when a program builds up a lot of pending operations that need to performed after the current execution. It can be observed when your program runs out of stack space. It is, strictly speaking, not a space leak, but an improper fix to a thunk leak or a streaming leak can convert it into a stack overflow, so we include it here. (We also emphasize these are not the same as thunk leaks, although sometimes they look the same.) These leaks thrive on recursion. You can fix them by converting recursive code to iterative style, which can be tail-call optimized, or using a better data structure. Turning on optimization also tends to help.

- A selector leak is a sub-species of a thunk leak when a thunk that only uses a subset of a record, but because it hasn’t been evaluated it causes the entire record to be retained. These have mostly been killed off by the treatment of GHC’s selector thunks by the RTS, but they also occasionally show due to optimizations. (See below.)

- An optimization induced leak is a camouflaged version of any of the leaks here, where the source code claims there is no leak, but an optimization by the compiler introduces the space leak. These are very tricky to identify; we would not put these in a petting zoo! (You can fix them by posting a bug to GHC Trac.)

- A thread leak is when too many Haskell threads are lying around. You can identify this by a contingent of TSO on the heap profile: TSO stands for thread-state object. These are interesting to debug, because there are a variety of reasons why a thread may not dying.

In the next post, we’ll draw some pictures and give examples of each of these leaks. As an exercise, I invite interested readers to categorize the leaks we saw last time.

Update. I’ve separated thunk leaks from what I will now call “live variable leaks,” and re-clarified some other points, especially with respect to strong references. I’ll expand on what I think is the crucial conceptual difference between them in later posts.

May 13, 2011Short post, longer ones in progress.

One of the really neat things about the Par monad is how it explicitly reifies laziness, using a little structure called an IVar (also known in the literature as I-structures). An IVar is a little bit like an MVar, except that once you’ve put a value in one, you can never take it out again (and you’re not allowed to put another value in.) In fact, this precisely corresponds to lazy evaluation.

The key difference is that an IVar splits up the naming of a lazy variable (the creation of the IVar), and specification of whatever code will produce the result of the variable (the put operation on an IVar). Any get to an empty IVar will block, much the same way a second attempt to evaluate a thunk that is being evaluated will block (a process called blackholing), and will be fulfilled once the “lazy computation” completes (when the put occurs.)

It is interesting to note that this construction was adopted precisely because laziness was making it really, really hard to reason about parallelism. It also provides some guidance for languages who might want to provide laziness as a built-in construct (hint: implementing it as a memoized thunk might not be the best idea!)

May 11, 2011I’m currently collecting non-stack-overflow space leaks, in preparation for a future post in the Haskell Heap series. If you have any interesting space leaks, especially if they’re due to laziness, send them my way.

Here’s what I have so far (unverified: some of these may not leak or may be stack overflows. I’ll be curating them soon).

import Control.Concurrent.MVar

-- http://groups.google.com/group/fa.haskell/msg/e6d1d5862ecb319b

main1 = do file <- getContents

putStrLn $ show (length $ lines file) ++ " " ++

show (length $ words file) ++ " " ++

show (length file)

-- http://www.haskell.org/haskellwiki/Memory_leak

main2 = let xs = [1..1000000::Integer]

in print (sum xs * product xs)

-- http://hackage.haskell.org/trac/ghc/ticket/4334

leaky_lines :: String -> [String]

leaky_lines "" = []

leaky_lines s = let (l, s') = break (== '\n') s

in l : case s' of

[] -> []

(_:s'') -> leaky_lines s''

-- http://stackoverflow.com/questions/5552433/how-to-reason-about-space-complexity-in-haskell

data MyTree = MyNode [MyTree] | MyLeaf [Int]

makeTree :: Int -> MyTree

makeTree 0 = MyLeaf [0..99]

makeTree n = MyNode [ makeTree (n - 1)

, makeTree (n - 1) ]

count2 :: MyTree -> MyTree -> Int

count2 r (MyNode xs) = 1 + sum (map (count2 r) xs)

count2 r (MyLeaf xs) = length xs

-- http://stackoverflow.com/questions/2777686/how-do-i-write-a-constant-space-length-function-in-haskell

leaky_length xs = length' xs 0

where length' [] n = n

length' (x:xs) n = length' xs (n + 1)

-- http://stackoverflow.com/questions/3190098/space-leak-in-list-program

leaky_sequence [] = [[]]

leaky_sequence (xs:xss) = [ y:ys | y <- xs, ys <- leaky_sequence xss ]

-- http://hackage.haskell.org/trac/ghc/ticket/917

initlast :: (()->[a]) -> ([a], a)

initlast xs = (init (xs ()), last (xs ()))

main8 = print $ case initlast (\()->[0..1000000000]) of

(init, last) -> (length init, last)

-- http://hackage.haskell.org/trac/ghc/ticket/3944

waitQSem :: MVar (Int,[MVar ()]) -> IO ()

waitQSem sem = do

(avail,blocked) <- takeMVar sem

if avail > 0 then

putMVar sem (avail-1,[])

else do

b <- newEmptyMVar

putMVar sem (0, blocked++[b])

takeMVar b

-- http://hackage.haskell.org/trac/ghc/ticket/2607

data Tree a = Tree a [Tree a] deriving Show

data TreeEvent = Start String

| Stop

| Leaf String

deriving Show

main10 = print . snd . build $ Start "top" : cycle [Leaf "sub"]

type UnconsumedEvent = TreeEvent -- Alias for program documentation

build :: [TreeEvent] -> ([UnconsumedEvent], [Tree String])

build (Start str : es) =

let (es', subnodes) = build es

(spill, siblings) = build es'

in (spill, (Tree str subnodes : siblings))

build (Leaf str : es) =

let (spill, siblings) = build es

in (spill, Tree str [] : siblings)

build (Stop : es) = (es, [])

build [] = ([], [])

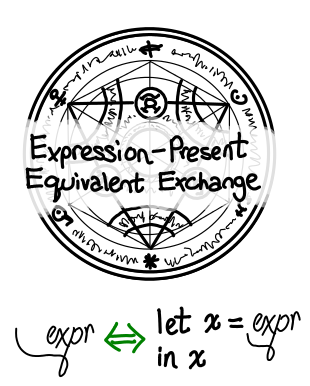

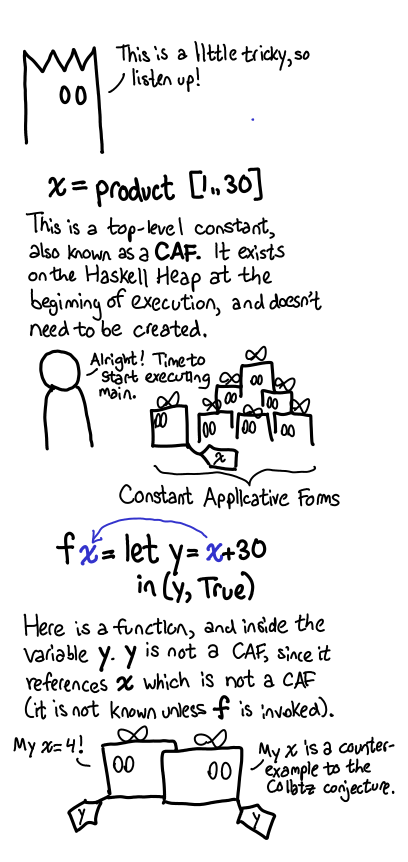

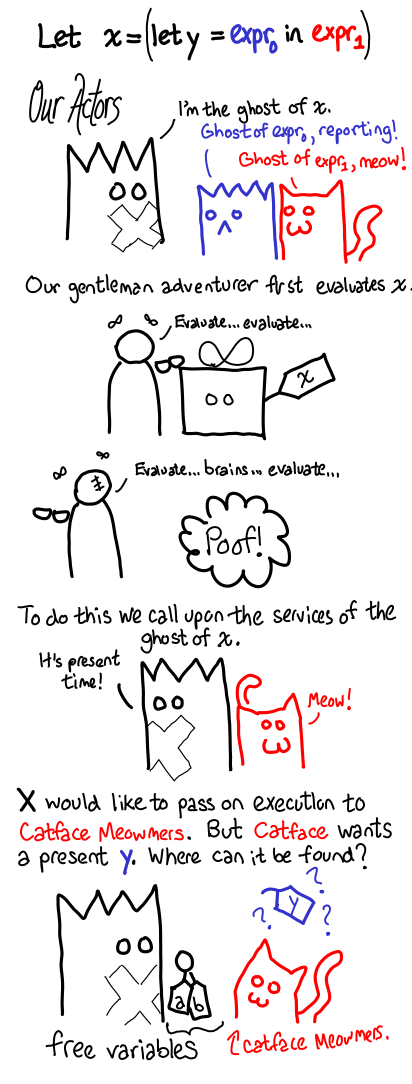

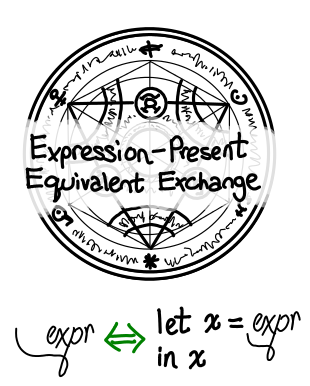

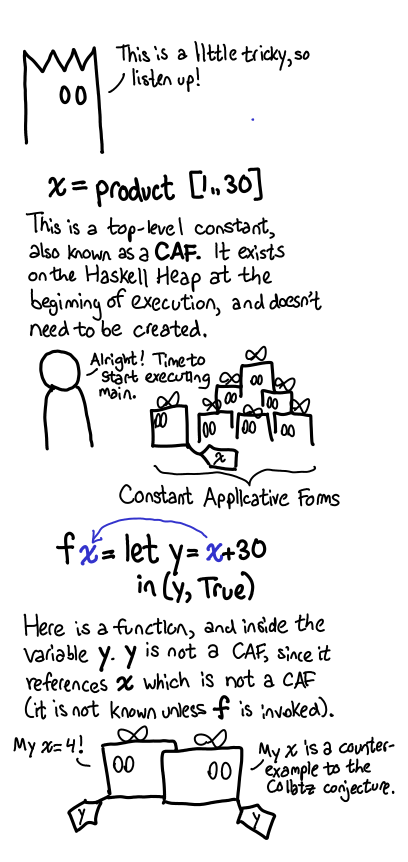

May 9, 2011Today, we discuss how presents on the Haskell Heap are named, whether by top-level bindings, let-bindings or arguments. We introduce the Expression-Present Equivalent Exchange, which highlights the fact that expressions are also thunks on the Haskell heap. Finally, we explain how this let-bindings inside functions can result in the creation of more presents, as opposed to constant applicative forms (CAFs) which exist on the Haskell Heap from the very beginning of execution.

When we’ve depicted presents on the Haskell Heap, they usually have names.

We’ve been a bit hush-hush about where these names come from, however. Partially, this is because the source of most of these names is straight-forward: they’re simply top-level bindings in a Haskell program:

y = 1

maxDiameter = 100

We also have names that come as bindings for arguments to a function. We’ve also discussed these when we talked about functions. You insert a label into the machine, and that label is how the ghost knows what the “real” location of x is:

f x = x + 3

pred = \x -> x == 2

So if I write f maxDiameter the ghost knows that wherever it sees x it should instead look for maxDiameter. But this explanation has some gaps in it. What if I write f (x + 2): what’s the label for x + 2?

One way to look at this is to rewrite this function in a different way: let z = x + 2 in f z, where z is a fresh variable: one that doesn’t show up anywhere else in the expression. So, as long as we understand what let does, we understand what the compact f (x + 2) does. I’ll call this the Expression-Present Equivalent Exchange.

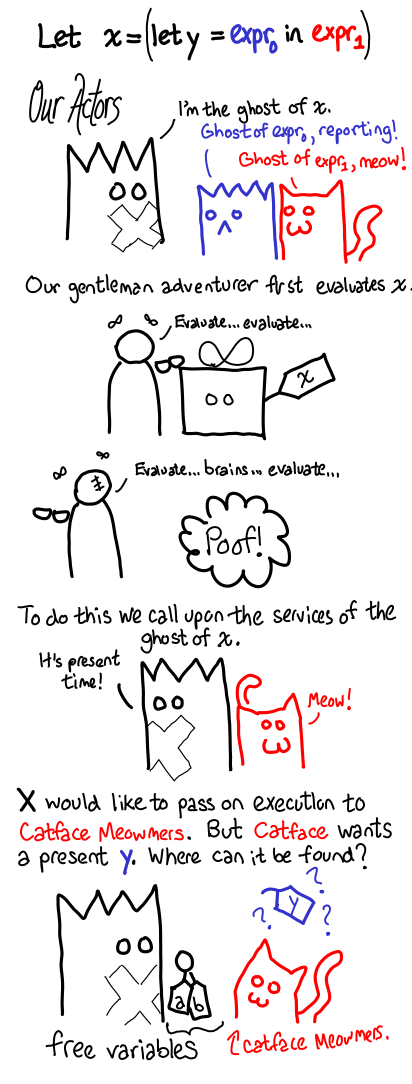

But what does let do anyway?

Sometimes, exactly the same job as a top-level binding. These are Constant Applicative Forms (CAF).

So we just promote the variable to the global heap, give it some unique name and then it’s just like the original situation. We don’t even need to re-evaluate it on a subsequent call to the function. To reiterate, the key difference is free variables (see bottom of post for a glossary): a constant-applicative form has no free variables, whereas most let bindings we write have free variables.

Glossary. The definition of free variables is pretty useful, even if you’ve never studied the lambda calculus. The free variables of an expression are variables for which I don’t know the value of simply by looking at the expression. In the expression x + y, x and y are free variables. They’re called free variables because a lambda “captures” them: the x in \x -> x is not free, because it is defined by the lambda \x ->. Formally:

fv(x) = {x}

fv(e1 e2) = fv(e1) `union` fv(e2)

fv(\x -> e1) = fv(e1) - {x}

If we do have free variables, things are a little trickier. So here is an extended comic explaining what happens when you force a thunk that is a let binding.

Notice how the ghosts pass the free variables around. When a thunk is left unevaluated, the most important things to look at are its free variables, as those are the other thunks that will have been left unevaluated. It’s also worth repeating that functions always take labels of presents, never actual unopened presents themselves.

The rules are very simple, but the interactions can be complex!

Last time: How the Grinch stole the Haskell Heap

Technical notes. When writing strict mini-languages, a common trick when implementing let is to realize that it is actually syntax sugar for lambda application: let x = y in z is the same as (\x -> z) y. But this doesn’t work for lazy languages: what if y refers to x? In this case, we have a recursive let binding, and usually you need to use a special let-rec construction instead, which requires some mutation. But in a lazy language, it’s easy: making the binding will never evaluate the right-hand side of the equation, so I can set up each variable at my leisure. I also chose to do the presentation in the opposite way because I want people to always be thinking of names. CAFs don’t have names, but for all intents and purposes they’re global data that does get shared, and so naming it is useful if you’re trying to debug a CAF-related space leak.

Perhaps a more accurate translation for f (x + 2) is f (let y = x + 2 in y), but I thought that looked kind of strange. My apologies.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

May 6, 2011One of the persistent myths about Aristotelean physics—the physics that was proposed by the Ancient Greeks and held up until Newton and Galileo came along—is that Aristotle thought that “heavier objects fall more quickly than light objects”, the canonical example being that of a cannon ball and feather. Although some fraction of contemporary human society may indeed believe this “fact,” Aristotle had a far more subtle and well-thought out view on the matter. If you don’t believe me, an English translation of his original text (Part 8) adequately gives off this impression. Here is a relevant quote (emphasis mine):

We see the same weight or body moving faster than another for two reasons, either because there is a difference in what it moves through, as between water, air, and earth, or because, other things being equal, the moving body differs from the other owing to excess of weight or of lightness.

The “other things being equal” is a critical four words that are left out even of Roman accounts of the theory. See for example Roman philosopher Lucretius:

For whenever bodies fall through water and thin air, they quicken their descents in proportion to their weights…

While I do not mean to imply the Aristotle was correct or at all near a Newtonian conception of physics, Aristotle was cognizant of the fact that the shape of the falling object could affect its descent (“For a moving thing cleaves the medium either by its shape”) and in fact, the context of these quotes is not a treatise on how bodies move, but about how bodies move through a medium: in particular, Aristotle is attempting to argue how bodies might move in “the void.” But somehow, this statement got misinterpreted into a myth that the majority of Westerners believed up until the advent of Galilean physics. Where did all of these essential details go?

My belief is that Aristotle lacked the crucial conceptual framework—Newtonian physics—to fit these disparate facts together. Instead, Aristotle believed in the teleological principal, that all bodies had natural places which they natural moved toward, which failed to have any explanatory power for many instances of physical experience. What generalizations he were able to make were riddled with special cases and the need for careful thought, that made the ideas difficult to be communicated without losing something in the process. This is not to say the careful thinking is not necessary: even when we teach physics today, it is extremely easy to make the same mistakes that our historic predecessors made: the facts of the matter may all “be in Newton’s laws”, but it’s not necessarily obvious that this is the case!

But as you learn about the applications of a theory, about the places where it easily can go wrong, it is critical to remember that these thoughts and intuitions are to be hung on the grander tree of the unifying and adequate theory. Those who do not are forever doomed to juggling a confusing panoply of special cases and disjoint facts and cursed with the inability to concisely express their ideas. And though I have not the space to argue it here, I also claim that this applies for every other sort of discipline for which you must accumulate knowledge.

tl;dr — Facts without structure are facts easily forgotten.

May 4, 2011When we teach beginners about Haskell, one of the things we handwave away is how the IO monad works. Yes, it’s a monad, and yes, it does IO, but it’s not something you can implement in Haskell itself, giving it a somewhat magical quality. In today’s post, I’d like to unravel the mystery of the IO monad by describing how GHC implements the IO monad internally in terms of primitive operations and the real world token. After reading this post, you should be able to understand the resolution of this ticket as well as the Core output of this Hello World! program:

main = do

putStr "Hello "

putStrLn "world!"

Nota bene: This is not a monad tutorial. This post assumes the reader knows what monads are! However, the first section reviews a critical concept of strictness as applied to monads, because it is critical to the correct functioning of the IO monad.

As a prelude to the IO monad, we will briefly review the State monad, which forms the operational basis for the IO monad (the IO monad is implemented as if it were a strict State monad with a special form of state, though there are some important differences—that’s the magic of it.) If you feel comfortable with the difference between the lazy and strict state monad, you can skip this section. Otherwise, read on. The data type constructor of the State monad is as follows:

newtype State s a = State { runState :: s -> (a, s) }

A running a computation in the state monad involves giving it some incoming state, and retrieving from it the resulting state and the actual value of the computation. The monadic structure involves threading the state through the various computations. For example, this snippet of code in the state monad:

do x <- doSomething

y <- doSomethingElse

return (x + y)

could be rewritten (with the newtype constructor removed) as:

\s ->

let (x, s') = doSomething s

(y, s'') = doSomethingElse s' in

(x + y, s'')

Now, a rather interesting experiment I would like to pose for the reader is this: suppose that doSomething and doSomethingElse were traced: that is, when evaluated, they outputted a trace message. That is:

doSomething s = trace "doSomething" $ ...

doSomethingElse s = trace "doSomethingElse" $ ...

Is there ever a situation in which the trace for doSomethingElse would fire before doSomething, in the case that we forced the result of the elements of this do block? In a strict language, the answer would obviously be no; you have to do each step of the stateful computation in order. But Haskell is lazy, and in another situation it’s conceivable that the result of doSomethingElse might be requested before doSomething is. Indeed, here is such an example of some code:

import Debug.Trace

f = \s ->

let (x, s') = doSomething s

(y, s'') = doSomethingElse s'

in (3, s'')

doSomething s = trace "doSomething" $ (0, s)

doSomethingElse s = trace "doSomethingElse" $ (3, s)

main = print (f 2)

What has happened is that we are lazy in the state value, so when we demanded the value of s'', we forced doSomethingElse and were presented with an indirection to s', which then caused us to force doSomething.

Suppose we actually did want doSomething to always execute before doSomethingElse. In this case, we can fix things up by making our state strict:

f = \s ->

case doSomething s of

(x, s') -> case doSomethingElse s' of

(y, s'') -> (3, s'')

This subtle transformation from let (which is lazy) to case (which is strict) lets us now preserve ordering. In fact, it will turn out, we won’t be given a choice in the matter: due to how primitives work out we have to do things this way. Keep your eye on the case: it will show up again when we start looking at Core.

Bonus. Interestingly enough, if you use irrefutable patterns, the case-code is equivalent to the original let-code:

f = \s ->

case doSomething s of

~(x, s') -> case doSomethingElse s' of

~(y, s'') -> (3, s'')

The next part of our story are the primitive types and functions provided by GHC. These are the mechanism by which GHC exports types and functionality that would not be normally implementable in Haskell: for example, unboxed types, adding together two 32-bit integers, or doing an IO action (mostly, writing bits to memory locations). They’re very GHC specific, and normal Haskell users never see them. In fact, they’re so special you need to enable a language extension to use them (the MagicHash)! The IO type is constructed with these primitives in GHC.Types:

newtype IO a = IO (State# RealWorld -> (# State# RealWorld, a #))

In order to understand the IO type, we will need to learn about a few of these primitives. But it should be very clear that this looks a lot like the state monad…

The first primitive is the unboxed tuple, seen in code as (# x, y #). Unboxed tuples are syntax for a “multiple return” calling convention; they’re not actually real tuples and can’t be put in variables as such. We’re going to use unboxed tuples in place of the tuples we saw in runState, because it would be pretty terrible if we had to do heap allocation every time we performed an IO action.

The next primitive is State# RealWorld, which will correspond to the s parameter of our state monad. Actually, it’s two primitives, the type constructor State#, and the magic type RealWorld (which doesn’t have a # suffix, fascinatingly enough.) The reason why this is divided into a type constructor and a type parameter is because the ST monad also reuses this framework—but that’s a matter for another blog post. You can treat State# RealWorld as a type that represents a very magical value: the value of the entire real world. When you ran a state monad, you could initialize the state with any value you cooked up, but only the main function receives a real world, and it then gets threaded along any IO code you may end up having executing.

One question you may ask is, “What about unsafePerformIO?” In particular, since it may show up in any pure computation, where the real world may not necessarily available, how can we fake up a copy of the real world to do the equivalent of a nested runState? In these cases, we have one final primitive, realWorld# :: State# RealWorld, which allows you to grab a reference to the real world wherever you may be. But since this is not hooked up to main, you get absolutely no ordering guarantees.

Let’s return to the Hello World program that I promised to explain:

main = do

putStr "Hello "

putStrLn "world!"

When we compile this, we get some core that looks like this (certain bits, most notably the casts (which, while a fascinating demonstration of how newtypes work, have no runtime effect), pruned for your viewing pleasure):

Main.main2 :: [GHC.Types.Char]

Main.main2 = GHC.Base.unpackCString# "world!"

Main.main3 :: [GHC.Types.Char]

Main.main3 = GHC.Base.unpackCString# "Hello "

Main.main1 :: GHC.Prim.State# GHC.Prim.RealWorld

-> (# GHC.Prim.State# GHC.Prim.RealWorld, () #)

Main.main1 =

\ (eta_ag6 :: GHC.Prim.State# GHC.Prim.RealWorld) ->

case GHC.IO.Handle.Text.hPutStr1

GHC.IO.Handle.FD.stdout Main.main3 eta_ag6

of _ { (# new_s_alV, _ #) ->

case GHC.IO.Handle.Text.hPutStr1

GHC.IO.Handle.FD.stdout Main.main2 new_s_alV

of _ { (# new_s1_alJ, _ #) ->

GHC.IO.Handle.Text.hPutChar1

GHC.IO.Handle.FD.stdout System.IO.hPrint2 new_s1_alJ

}

}

Main.main4 :: GHC.Prim.State# GHC.Prim.RealWorld

-> (# GHC.Prim.State# GHC.Prim.RealWorld, () #)

Main.main4 =

GHC.TopHandler.runMainIO1 @ () Main.main1

:Main.main :: GHC.Types.IO ()

:Main.main =

Main.main4

The important bit is Main.main1. Reformatted and renamed, it looks just like our desugared state monad:

Main.main1 =

\ (s :: State# RealWorld) ->

case hPutStr1 stdout main3 s of _ { (# s', _ #) ->

case hPutStr1 stdout main2 s' of _ { (# s'', _ #) ->

hPutChar1 stdout hPrint2 s''

}}

The monads are all gone, and hPutStr1 stdout main3 s, while ostensibly always returning a value of type (# State# RealWorld, () #), has side-effects. The repeated case-expressions, however, ensure our optimizer doesn’t reorder the IO instructions (since that would have a very observable effect!)

For the curious, here are some other notable bits about the core output:

- Our

:main function (with a colon in front) doesn’t actually go straight to our code: it invokes a wrapper function GHC.TopHandler.runMainIO which does some initialization work like installing the top-level interrupt handler. unpackCString# has the type Addr# -> [Char], so what it does it transforms a null-terminated C string into a traditional Haskell string. This is because we store strings as null-terminated C strings whenever possible. If a null byte or other nasty binary is embedded, we would use unpackCStringUtf8# instead.putStr and putStrLn are nowhere in sight. This is because I compiled with -O, so these function calls got inlined.

To emphasize how important ordering is, consider what happens when you mix up seq, which is traditionally used with pure code and doesn’t give any order constraints, and IO, for which ordering is very important. That is, consider Bug 5129. Simon Peyton Jones gives a great explanation, so I’m just going to highlight how seductive (and wrong) code that isn’t ordered properly is. The code in question is x `seq` return (). What does this compile to? The following core:

case x of _ {

__DEFAULT -> \s :: State# RealWorld -> (# s, () #)

}

Notice that the seq compiles into a case statement (since case statements in Core are strict), and also notice that there is no involvement with the s parameter in this statement. Thus, if this snippet is included in a larger fragment, these statements may get optimized around. And in fact, this is exactly what happens in some cases, as Simon describes. Moral of the story? Don’t write x `seq` return () (indeed, I think there are some instances of this idiom in some of the base libraries that need to get fixed.) The new world order is a new primop:

case seqS# x s of _ {

s' -> (# s', () #)

}

Much better!

This also demonstrates why seq x y gives absolutely no guarantees about whether or not x or y will be evaluated first. The optimizer may notice that y always gives an exception, and since imprecise exceptions don’t care which exception is thrown, it may just throw out any reference to x. Egads!

- Most of the code that defines IO lives in the

GHC supermodule in base, though the actual IO type is in ghc-prim. GHC.Base and GHC.IO make for particularly good reading. - Primops are described on the GHC Trac.

- The ST monad is also implemented in essentially the exact same way: the unsafe coercion functions just do some type shuffling, and don’t actually change anything. You can read more about it in

GHC.ST.

May 2, 2011It is well known that unsafePerformIO is an evil tool by which impure effects can make their way into otherwise pristine Haskell code. But is the rest of Haskell really that pure? Here are a few questions to ask:

- What is the value of

maxBound :: Int? - What is the value of

\x y -> x / y == (3 / 7 :: Double) with 3 and 7 passed in as arguments? - What is the value of

os :: String from System.Info? - What is the value of

foldr (+) 0 [1..100] :: Int?

The answers to each of these questions are ill-defined—or you might say they’re well defined, but you need a little extra information to figure out what the actual result is.

- The Haskell 98 Report guarantees that the value of

Int is at least -2^29 to 2^29 - 1. But the precise value depends on what implementation of Haskell you’re using (does it need a bit for garbage collection purposes) and whether or not you’re on a 32-bit or 64-bit system. - Depending on whether or not the excess precision of your floating point registers is used to calculate the division, or if the IEEE standard is adhered to, this equality may or may not hold.

- Depending on what operating system the program is run on this value will change.

- Depending on the stack space allotted to this program at runtime, it may return a result or it may stack overflow.

In some respects, these constructs break referential transparency in an interesting way: while their values are guaranteed to be consistent during a single execution of the program, they may vary between different compilations and runtime executions of our program.

Is this kosher? And if it’s not, what are we supposed to say about the semantics of these Haskell programs?

The topic came up on #haskell, and I and a number of participants had a lively discussion about the topic. I’ll try to distill a few of the viewpoints here.

- The mathematical school says that all of this is very unsatisfactory, and that their programming languages should adhere to some precise semantics over all compilations and runtime executions. People ought to use arbitrary-size integers, and if they need modular arithmetic specify explicitly how big the modulus is (

Int32? Int64?) os is an abomination that should have been put in the IO sin bin. As tolkad puts it, “Without a standard you are lost, adrift in a sea of unspecified semantics. Hold fast to the rules of the specification lest you be consumed by ambiguity.” Limitations of the universe we live in are something of an embarrassment to the mathematician, but as long as the program crashes with a nice stack overflow they’re willing to live with a partial correctness result. An interesting subgroup is the distributed systems school which also care about the assumptions that are being made about the computing environment, but for a very practical reason. If multiple copies of your program are running on heterogeneous machines, you better not make any assumptions about pointer size on the wire. - The compile time school says that the mathematical approach is untenable for real world programming: one should program with compilation in mind. They’re willing to put up with a little bit of uncertainty in their source code programs, but all of the ambiguity should be cleared up once the program is compiled. If they’re feeling particularly cavalier, they’ll write their program with several meanings in mind, depending on the compile time options. They’re willing to put up with stack overflows, which are runtime determined, but are also a little uncomfortable with it. It is certainly better than the situation with

os, which could vary from runtime to runtime. The mathematicians make fun of them with examples like, “What about a dynamic linker or virtual machine, where some of the compilation is left off until runtime?” - The run time school says “Sod referential transparency across executions” and only care about internal consistency across a program run. Not only are they OK with stack overflows, they’re also OK with command line arguments setting global (pure!) variables, since those don’t change within the executions (they perhaps think

getArgs should have had the signature [String], not IO [String]), or variables that unsafely read in the contents of an external data file at program startup. They write things in docs like “This integer need not remain consistent from one execution of an application to another execution of the same application.” Everyone else sort of shudders, but it’s a sort of guilty pleasure that most people have indulged in at some point or another.

So, which school are you a member of?

Postscript. Since Rob Harper has recently posted another wonderfully iconoclastic blog post, and because his ending remarks are tangentially related to the topic of this post (purity), I thought I couldn’t help but sneak in a few remarks. Rob Harper states:

So why don’t we do this by default? Because it’s not such a great idea. Yes, I know it sounds wonderful at first, but then you realize that it’s pretty horrible. Once you’re in the IO monad, you’re stuck there forever, and are reduced to Algol-style imperative programming. You cannot easily convert between functional and monadic style without a radical restructuring of code. And you inevitably need unsafePerformIO to get anything serious done. In practical terms, you are deprived of the useful concept of a benign effect, and that just stinks!

I think Harper overstates the inability to write functional-style imperative programs in Haskell (conversions from functional to monadic style, while definitely annoying in practice, are relatively formulaic.) But these practical concerns do influence the day-to-day work of programmers, and as we’ve seen here, purity comes in all sorts of shades of gray. There is design space both upwards and downwards of Haskell’s current situation, but I think to say that purity should be thrown out entirely is missing the point.

April 29, 2011Today, we introduce the Grinch.

A formerly foul and unpleasant character, the Grinch has reformed his ways. He still has a penchant for stealing presents, but these days he does it ethically: he only takes a present if no one cares about it anymore. He is the garbage collector of the Haskell Heap, and he plays a very important role in keeping the Haskell Heap small (and thus our memory usage low)—especially since functional programs generate a lot of garbage. We’re not a particularly eco-friendly bunch.

The Grinch also collects garbage in traditional imperative languages, since the process is fundamentally the same. (We describe copying collection using Cheney’s algorithm here.) The Grinch first asks us what objects in the heap we care about (the roots). He moves these over to a new heap (evacuation), which will contain objects that will be saved. Then he goes over the objects in the new heap one by one, making sure they don’t point to other objects on the old heap. If they do, he moves those presents over too (scavenging). Eventually, he’s checked all of the presents in the new heap, which means everything left-over is garbage, and he drags it away.

But there are differences between the Haskell Heap and a traditional heap.

A traditional heap is one in which all of the presents have been opened: there will only be unwrapped boxes and gift-cards, so the Grinch only needs to check what gifts the gift-cards refer to in order to decide what else to scavenge.

However, the Haskell Heap has unopened presents, and the ghosts that haunt these presents are also pretty touchy when it comes to presents they know about. So the Grinch has to consult with them and scavenge any presents they point to.

How do presents become garbage? In both the Haskell Heap and a traditional heap, a present obviously becomes garbage if we tell the Grinch we don’t care about it anymore (the root set changes). Furthermore, if a gift-card is edited to point to a different present, the present it used to point to might also become unwanted (mutation). But what is distinctive about the Haskell Heap is this: after we open a present (evaluate a thunk), the ghost disappears into the ether, its job done. The Grinch may now be able to garbage collect the presents the ghost previously cared about.

Let’s review the life-cycle of a present on the Haskell Heap, in particular emphasizing the present’s relationship to other presents on the heap. (The phase names are actually used by GHC’s heap profiling.)

Suppose we want to minimize our memory usage by keeping the number of presents in our heap low. There are two ways to do this: we can reduce the number of presents we care about or we can reduce the number of presents we create. The former corresponds to making presents go dead, usually by opening a present and releasing any presents the now absent ghost cared about. The latter corresponds to avoiding function application, usually by not opening presents when unnecessary.

So, which one results in a smaller heap? It depends!

It is not true that only laziness causes space leaks on the heap. Excessive strictness can cause space leaks too. The key to fixing an identified space leak is figuring out which is the case. Nota bene: I’ve said a lot about space leaks, but I haven’t touched on a common space leak that plagues many people: space leaks on the stack. Stick around.

Last time: Functions produce the Haskell Heap

Next time: Bindings and CAFs on the Haskell Heap

Technical notes. The metaphor of the Grinch moving presents from one pile to another is only accurate if we assume copying garbage collections (GHC also has a compacting garbage collector, which operates differently), and some details (notably how the Grinch knows that a present has already been moved to the new heap, and how the Grinch keeps track of how far into the new heap he is) were skipped over. Additionally, the image of the Grinch “dragging off the garbage presents” is a little misleading: we just overwrite the old memory! Also, GHC doesn’t only have one heap: we have a generational garbage collector, which effectively means there are multiple heaps (and the Grinch visits the young heap more frequently than the old heaps.)

Presents and gift cards look exactly the same to a real garbage collector: a gift card is simply a pointer to a constructor info table and some pointer fields, whereas a present (thunk) is simply a pointer to the info table for the executable code and some fields for its closure variables. For Haskell, which treats data as code, they are one and the same. An implementation of anonymous functions in a language without them built-in might manually represent them as a data structure pointing to the static function code and extra space for its arguments. After all, evaluation of a lazy value is just a controlled form of mutation!

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

April 27, 2011We’ve talked about how we open (evaluate) presents (thunks) in the Haskell Heap: we use IO. But where do all of these presents come from? Today we introduce where all these presents come from, the Ghost-o-matic machine (a function in a Haskell program).

Using a function involves three steps.

We can treat the machine as a black box that takes present labels and pops out presents, but you can imagine the inside as having an unlimited supply of identical ghosts and empty present boxes: when you run the machine, it puts a copy of the ghost in the box.

If the ghosts we put into the presents are identical, do they all behave the same way? Yes, but with one caveat: the actions of the ghost are determined by a script (the original source code), but inside the script there are holes that are filled in by the labels you inserted into the machine.

Since there’s not actually anything in the boxes, we can precisely characterize a present by the ghost that haunts it.

A frequent problem that people who use the Ghost-o-matic run into is that they expect it to work the same way as the Strict-o-matic (a function in a traditional, strictly evaluated language.) They don’t even take the same inputs: the Strict-o-matic takes unwrapped, unhaunted (unlifted) objects and gift cards, and outputs other unhaunted presents and gift cards.

But it’s really easy to forget, because the source-level syntax for strict function application and lazy function application are very similar.

This is a point that must be thoroughly emphasized. In fact, in order to emphasize it, I’ve drawn two more pictures to reiterate what the permitted inputs and outputs for a Ghost-o-matic machine are.

Ghost-o-matics take labels of presents, not the actual presents themselves. This importantly means that the Ghost-o-matic doesn’t open any presents: after all, it only has labels, not the actual present. This stands in contrast to a Strict-o-matic machine which takes presents as inputs and opens them: one might call this machine the force function, of type Thunk a -> a. In Haskell, there is no such thing.

The Ghost-o-matic always creates a wrapped present. It will never produce an unwrapped present, even if there is no ghost haunting the present (the function was a constant).

We state previously that there is no force function in Haskell. But the function seq seems to do something very like forcing a thunk. A present haunted by a seq ghost, when opened, will cause two other presents to be opened (even if the first one is unnecessary). It seems like the first argument is forced; and so seq x x might be some reasonable approximation of force in an imperative language. But what happens when we actually open up a present haunted by the seq ghost?

Although the ghost ends up opening the present rather than us, it’s too late for it to do any good: immediately after the ghost opens the present, we would have gone to open it (which it already is). The key observation is that the seq x x ghost only opens the present x when the present seq x x is opened, and immediately after seq x x is opened we have to go open x by means of an indirection. The strictness of the seq ghost is defeated by the fact that it’s put in a present, not to be opened until x is desired.

One interesting observation is that the Strict-o-matic machine does things when its run. It can open presents, fire missiles or do other side effects.

But the Ghost-o-matic machine doesn’t do any of that. It’s completely pure.

To prevent confusion, users of the Strict-o-matic and Ghost-o-matic machines may find it useful to compare the the present creation life-cycle for each of the machines.

The lazy Ghost-o-matic machine is split into two discrete phases: the function application, which doesn’t actually do anything, just creates the present, and the actual opening of the present. The Strict-o-matic does it all in one bang—although it could output a present (that’s what happens when you implement laziness inside a strict language). But in a strict language, you have to do it all yourself.

The Ghost-o-matic is approved for use by both humans and ghosts.

This does mean that opening a haunted present may produces more presents. For example, if the present produces a gift card for presents that don’t already live on the heap.

For a spine-strict data structure, it can produce a lot more presents.

Oh, and one more thing: the Ghost-o-matic makes a great gift for ghosts and family. They can be gift-wrapped in presents too. After all, everything in Haskell is a present.

Technical notes. With optimizations, a function may not necessarily allocate on the heap. The only way to be sure is to check out what optimized Core the program produces. It’s also not actually true that traditional, strict functions don’t exist in Haskell: unboxed primitives can be used to write traditional imperative code. It may look scary, but it’s not much different than writing your program in ML.

I’ve completely ignored partial application, which ought to be the topic of a later post, but I will note that, internally speaking, GHC does try its very best to pass all of the arguments a function wants at application time; if all the arguments are available, it won’t bother creating a partially application (PAP). But these can be thought of modified Ghost-o-matics, whose ghost already has some (but not all) of its arguments. Gifted ghost-o-matics (functions in the heap) can also be viewed this way: but rather than pre-emptively giving the ghost some arguments, the ghost is instead given its free variables (closure).

Last time: Implementing the Haskell Heap in Python, v1

Next time: How the Grinch stole the Haskell Heap

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

April 25, 2011Here is a simple implementation of all of the parts of the Haskell heap we have discussed up until now, ghosts and all.

heap = {} # global

# ---------------------------------------------------------------------#

class Present(object): # Thunk

def __init__(self, ghost):

self.ghost = ghost # Ghost haunting the present

self.opened = False # Evaluated?

self.contents = None

def open(self):

if not self.opened:

# Hey ghost! Give me your present!

self.contents = self.ghost.disturb()

self.opened = True

self.ghost = None

return self.contents

class Ghost(object): # Code and closure

def __init__(self, *args):

self.tags = args # List of names of presents (closure)

def disturb(self):

raise NotImplemented

class Inside(object):

pass

class GiftCard(Inside): # Constructor

def __init__(self, name, *args):

self.name = name # Name of gift card

self.items = args # List of presents on heap you can redeem!

def __str__(self):

return " ".join([self.name] + map(str, self.items))

class Box(Inside): # Boxed, primitive data type

def __init__(self, prim):

self.prim = prim # Like an integer

def __str__(self):

return str(self.prim)

# ---------------------------------------------------------------------#

class IndirectionGhost(Ghost):

def disturb(self):

# Your present is in another castle!

return heap[self.tags[0]].open()

class AddingGhost(Ghost):

def disturb(self):

# Gotta make your gift, be back in a jiffy!

item_1 = heap[self.tags[0]].open()

item_2 = heap[self.tags[1]].open()

result = item_1.prim + item_2.prim

return Box(result)

class UnsafePerformIOGhost(Ghost):

def disturb(self):

print "Fire ze missiles!"

return heap[self.tags[0]].open()

class PSeqGhost(Ghost):

def disturb(self):

heap[self.tags[0]].open() # Result ignored!

return heap[self.tags[1]].open()

class TraceGhost(Ghost):

def disturb(self):

print "Tracing %s" % self.tags[0]

return heap[self.tags[0]].open()

class ExplodingGhost(Ghost):

def disturb(self):

print "Boom!"

raise Exception

# ---------------------------------------------------------------------#

def evaluate(tag):

print "> evaluate %s" % tag

heap[tag].open()

def makeOpenPresent(x):

present = Present(None)

present.opened = True

present.contents = x

return present

# Let's put some presents in the heap (since we can't make presents

# of our own yet.)

heap['bottom'] = Present(ExplodingGhost())

heap['io'] = Present(UnsafePerformIOGhost('just_1'))

heap['just_1'] = makeOpenPresent(GiftCard('Just', 'bottom'))

heap['1'] = makeOpenPresent(Box(1))

heap['2'] = makeOpenPresent(Box(2))

heap['3'] = makeOpenPresent(Box(3))

heap['traced_1']= Present(TraceGhost('1'))

heap['traced_2']= Present(TraceGhost('2'))

heap['traced_x']= Present(TraceGhost('x'))

heap['x'] = Present(AddingGhost('traced_1', '3'))

heap['y'] = Present(PSeqGhost('traced_2', 'x'))

heap['z'] = Present(IndirectionGhost('traced_x'))

print """$ cat src.hs

import Debug.Trace

import System.IO.Unsafe

import Control.Parallel

import Control.Exception

bottom = error "Boom!"

io = unsafePerformIO (putStrLn "Fire ze missiles" >> return (Just 1))

traced_1 = trace "Tracing 1" 1

traced_2 = trace "Tracing 2" 2

traced_x = trace "Tracing x" x

x = traced_1 + 3

y = pseq traced_2 x

z = traced_x

main = do

putStrLn "> evaluate 1"

evaluate 1

putStrLn "> evaluate z"

evaluate z

putStrLn "> evaluate z"

evaluate z

putStrLn "> evaluate y"

evaluate y

putStrLn "> evaluate io"

evaluate io

putStrLn "> evaluate io"

evaluate io

putStrLn "> evaluate bottom"

evaluate bottom

$ runghc src.hs"""

# Evaluating an already opened present doesn't do anything

evaluate('1')

# Evaluating an indirection ghost forces us to evaluate another present

evaluate('z')

# Once a present is opened, it stays opened

evaluate('z')

# Evaluating a pseq ghost may mean extra presents get opened

evaluate('y')

# unsafePerformIO can do anything, but maybe only once..

evaluate('io')

evaluate('io')

# Exploding presents may live in the heap, but they're only dangerous

# if you evaluate them...

evaluate('bottom')

Technical notes. You can already see some resemblance of the ghosts’ Python implementations and the actual Core GHC might spit out. Here’s an sample for pseq:

pseq =

\ (@ a) (@ b) (x :: a) (y :: b) ->

case x of _ { __DEFAULT -> y }

The case operation on x corresponds to opening x, and once it’s open we do an indirection to y (return heap['y'].open()). Here’s another example for the non-polymorphic adding ghost:

add =

\ (bx :: GHC.Types.Int) (by :: GHC.Types.Int) ->

case bx of _ { GHC.Types.I# x ->

case by of _ { GHC.Types.I# y ->

GHC.Types.I# (GHC.Prim.+# x y)

}

}

In this case, Box plays the role of GHC.Types.I#. See if you can come up with some of the other correspondences (What is pattern matching on bx and by? What is GHC.Prim.+# ?)

I might do the next version in C just for kicks (and because then it would actually look something like what a real heap in a Haskell program looks like.)

Last time: IO evaluates the Haskell Heap

Next time: Functions produce the Haskell Heap

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.