July 25, 2011What do these problems have in common: recursive equality/ordering checks, printing string representations, serializing/unserializing binary protocols, hashing, generating getters/setters? They are repetitive boilerplate pieces of code that have a strong dependence on the structure of the data they operate over. Since programmers love automating things away, various schools of thought have emerged on how to do this:

- Let your IDE generate this boilerplate for you. You right-click on the context menu, click “Generate

hashCode()”, and your IDE does the necessary program analysis for you; - Create a custom metadata format (usually XML), which you then run another program on which converts this description into code;

- Add sufficiently strong macro/higher-order capabilities to your language, so you can write programs which generate implementations in-program;

- Add sufficiently strong reflective capabilities to your language, so you can write a fully generic dynamic implementation for this functionality;

- Be a compiler and do static analysis over abstract syntax trees in order to figure out how to implement the relevant operations.

It hadn’t struck me how prevalent the fifth option was until I ran into wide scale use of one particular facet of the camlp4 system. While it describes itself as a “macro system,” in sexplib and bin-prot, the macros being used are not those of the C tradition (which would be good for implementing 3), rather, they are in the Lisp tradition, including access to the full syntax tree of OCaml and the ability to modify OCaml’s grammar. Unlike most Lisps, however, camlp4 has access to the abstract syntax tree of data type definitions (in untyped languages these are usually implicit), which it can use to transform into code.

One question that I’m interested in is whether or not this sort of metaprogramming can be made popular with casual users of languages. If I write code to convert a data structure into a Lisp-like version, is a logical next step to generalize this code into metaprogramming code, or is that a really large leap only to be done by extreme power users? At least from a user standpoint, camlp4 is extremely unobtrusive. In fact, I didn’t even realize I was using it until a month later! Using sexplib, for example, is a simple matter of writing:

type t = bar | baz of int * int

with sexp

Almost magically, sexp_of_t and sexp_to_t spring into existence.

But defining new transformations is considerably more involved. Part of the problem is the fact that the abstract-syntax tree you are operating over is quite complex, the unavoidable side-effect of making a language nice to program in. I could theoretically define all of the types I cared about using sums and products, but real OCaml programs use labeled constructors, records, anonymous types, anonymous variants, mutable fields, etc. So I have to write cases for all of these, and that’s difficult if I’m not already a language expert.

A possible solution for this is to define a simpler, core language on which to operate over, much the same way GHC Haskell compiles down to Core prior to code generation. You can then make the extra information available through an annotations system (which is desirable even when you have access to the full AST.) If the idea is fundamentally simple, don’t force the end-user to have to handle all of the incidental complexity that comes along with making a nice programming language. Unless, of course, they want to.

Postscript. One of the things I’m absolutely terrible at is literature search. As with most ideas, it’s a pretty safe bet to assume someone else has done this already. But I couldn’t find any prior art here. Maybe I need a better search query than “intermediate language for metaprogramming.”

July 22, 2011OCaml supports anonymous variant types, of the form type a = [`Foo of int | `Bar of bool], with the appropriate subtyping relations. Subtyping is, in general, kind of tricky, so I have been using these variant types fairly conservatively. (Even if a feature gives you too much rope, it can be manageable and useful if you use discipline.) Indeed, they are remarkably handy for one particular use-case for which I would have normally deployed GADTs. This is the “Combining multiple sum types into a single sum type” use-case.

Consider the following program in Haskell:

data A = Foo Int | Bar Bool

data B = Baz Char | Qux

If one would like to define the moral equivalent of A plus B, the most naive way to do this is:

data AorB = A A | B B

But this kind of sucks: I would have preferred some kind of flat namespace by which I could refer to A and B (also, this encoding is not equivalent to data AorB = Foo Int | Bar Bool | Baz Char | Qux in the presence of laziness.) If you use normal sum types in OCaml, you’re similarly out of luck. However, you can handily manage this if you use variant types:

type a = [`Foo of int | `Bar of bool]

type b = [`Baz of char | `Quz]

type a_or_b = [a | b]

Sweet! Note that we’re not using the full generality of variant types: I will only ever refer to these variant constructors in the context of a, b or a_or_b: anonymous variant types are right out. This prevents coercion messes.

I can actually pull this off in Haskell with GADTs, although it’s certainly not obvious for a beginning programmer:

data A

data B

data AorB t where

Foo :: Int -> AorB A

Bar :: Bool -> AorB A

Baz :: Char -> AorB B

Quz :: AorB B

To pattern match against all constructors, I specify the type AorB t; to only do A I use AorB A, and to only do B I use AorB B. Don’t ask me how to specify arbitrary subsets of more than two combined sum types. (Solutions in the comment section welcome, though they will be graded on clarity.)

The Haskell approach does have one advantage, which is that the sum type is still closed. Since OCaml can make no such guarantee, things like bin-prot need to use up a full honking four-bytes to specify what variant it is (they hash the name and use that as a unique identifier) rather than the two bits (but more likely, one byte) needed here. This also means for more efficient generated code.

July 20, 2011I’ll be at this year’s Hac Phi (coming up in a week and a half), and I am planning on working on in-program garbage collector statistics for GHC. There is nothing really technically difficult about this task (we just need to expose some functions in the RTS), but it’s not been done yet and I know quite a few performance-minded and long-running-server-minded folks who would love to see this functionality.

My question for you is this: what would you like such an API to look like? What things should it offer, how would you like to interact with it?

Here’s one sample API to get the ball rolling:

module GHC.RTS.Stats where

-- Info is not collected unless you run with certain RTS options. If

-- you are planning on using this on a long-running server, costs of the

-- options would be good to have (we also probably need to add extra

-- options which record, but have no outwardly visible effect.)

-- Read out static parameters that were provided via +RTS

generations :: IO Int

---------------------------------------------------------------------

-- Full statistics

-- Many stats are internally collected as words. Should be publish

-- words?

-- Names off of machine readable formats

bytesAllocated :: IO Int64

numGCs :: IO Int64

numByteUsageSamples :: IO Int64

averageBytesUsed :: IO Int64 -- cumulativeBytesUsed / numByteUsageSamples

maxBytesUsed :: IO Int64

-- peakMemoryBlocksAllocated :: IO Int64

peakMegabytesAllocated :: IO Int64

initCpuSeconds :: IO Double

initWallSeconds :: IO Double

mutatorCpuSeconds :: IO Double

mutatorWallSeconds :: IO Double

gcCpuSeconds :: IO Double

gcWallSeconds :: IO Double

-- Wouldn't be too unreasonable to offer a data structure with all of

-- this? Unclear. At least, it would prevent related data from

-- desynchronizing.

data GlobalStats = GlobalStats

{ g_bytes_allocated :: Int64

, g_num_GCs :: Int64

, g_num_byte_usage_samples :: Int64

, g_average_bytes_used :: Int64

, g_max_bytes_used :: Int64

, g_peak_megabytes_allocated :: Int64

, g_init_cpu_seconds :: Double

, g_init_wall_seconds :: Double

, g_mutator_cpu_seconds :: Double

, g_mutator_wall_seconds :: Double

, g_gc_cpu_seconds :: Double

, g_gc_wall_seconds :: Double

}

globalStats :: IO GlobalStats

generationStats :: Int -> IO GlobalStats

---------------------------------------------------------------------

-- GC statistics

-- We can't offer a realtime stream of GC events, because they come

-- to fast. (Test? eventlog comes to fast, maybe GC is manageable,

-- but you don't want to trigger GC in your handler.)

data GCStats = GCStats

{ gc_alloc :: Int64

, gc_live :: Int64

, gc_copied :: Int64

, gc_gen :: Int

, gc_max_copied :: Int64

, gc_avg_copied :: Int64

, gc_slop :: Int64

, gc_wall_seconds :: Int64

, gc_cpu_seconds :: Int64

, gc_faults :: Int

}

lastGC :: IO GCStats

lastMajorGC :: IO GCStats

allocationRate :: IO Double

---------------------------------------------------------------------

-- Parallel GC statistics

data ParGCStats = ParGCStats

{ par_avg_copied :: Int64

, par_max_copied :: Int64

}

parGCStats :: IO ParGCStats

parGCNodes :: IO Int64

---------------------------------------------------------------------

-- Threaded runtime statistics

data TaskStats = TaskStats

-- Inconsistent naming convention here: mut_time or mut_cpu_seconds?

-- mut_etime or mut_wall_seconds? Hmm...

{ task_mut_time :: Int64

, task_mut_etime :: Int64

, task_gc_time :: Int64

, task_gc_etime :: Int64

}

---------------------------------------------------------------------

-- Spark statistics

data SparkStats = SparkStats

{ s_created :: Int64

, s_dud :: Int64

, s_overflowed :: Int64

, s_converted :: Int64

, s_gcd :: Int64

, s_fizzled :: Int64

}

sparkStats :: IO SparkStats

sparkStatsCapability :: Int -> IO SparkStats

July 18, 2011In theory, Git supports custom, low-level merge drivers with the merge configuration properties. In practice, no one actually wants to write their own merge driver from scratch. Well, for many cases where a custom merge driver would come in handy, you don’t have to write your merge driver from scratch! Consider these cases:

- You want to merge files which have differing newline styles,

- You want to merge files where one had lots of trailing whitespace removed,

- You want to merge files one branch has replaced certain strings with custom strings (for example, a configuration file which instantiated

PASSWORD, or a file that needs to be anonymized if there is a merge conflict), - You want to merge a binary file that has a stable textual format, or

- You want to merge with knowledge about specific types of conflicts and how to resolve them (a super-smart

rerere).

For all of these cases, you can instead perform a synthetic Git merge by modifying the input files (constructing synthetic merge inputs), calling Git’s git merge-file to do the actual merge, and then possibly editing the result, before handing it back off to the original invoker of your merge driver. It’s really simple. Here’s an example driver that handles files with differing newline styles by canonicalizing them to UNIX:

#!/bin/sh

CURRENT="$1"

ANCESTOR="$2"

OTHER="$3"

dos2unix "$CURRENT"

dos2unix "$ANCESTOR"

dos2unix "$OTHER"

exec git merge-file "$CURRENT" "$ANCESTOR" "$OTHER"

You can then set it up by frobbing your .git/config:

[merge.nl]

name = Newline driver

driver = /home/ezyang/merge-fixnewline.sh %A %O %B

And your .git/info/attributes:

*.txt merge=nl

In Wizard, we implemented (more clever) newline canonicalization, configuration value de-substitution (this reduces the diff between upstream and downstream, reducing the amount of conflicts due to proximity), and custom rerere behavior. I’ve also seen a coworker of mine use this technique manually to handle merge conflicts involving trailing whitespace (in Mercurial, no less!)

Actually, we took this concept further: rather than only create synthetic files, we create entirely synthetic trees, and then call git merge on them proper. This has several benefits:

- We can now pick an arbitrary ancestor commit to perform the merge from (this, surprisingly enough, really comes in handy for our use-case),

- Git has an easier time detecting when files moved and changed newline style, etc, and

- It’s a bit easier to use, since you just call a custom command rather than have to remember how to setup your Git config and attributes properly (and keep them up to date!)

Merges are just metadata—multiple parents commits. Git doesn’t care how you get the contents of your merge commit. Happy merging!

July 15, 2011It is not too difficult (scroll to “Non sequitur”) to create a combinator which combines two folds into a single fold that operates on a single input list in one pass. This is pretty important if your input list is pretty big, since doing the folds separately could result in a space leak, as might be seen in the famous “average” space leak:

import Data.List

big = [1..10000000]

sum' = foldl' (+) 0

average xs = fromIntegral (sum' xs) / fromIntegral (length xs)

main = print (average big)

(I’ve redefined sum so we don’t stack overflow.) I used to think combining functions for folds were pretty modular, since they had a fairly regular interface, could be combined together, and really represented the core notion of when it was possible to eliminate such a space leak: obviously, if you have two functions that require random access to elements of the list, they’ll retain the entirety of it all the way through.

Of course, a coworker of mine complained, “No! That’s not actually modular!” He wanted to write the nice version of the code, not some horrible gigantic fold function. This got me thinking: is it actually true that the compiler can’t figure out when two computations on a streaming data structure can be run in parallel?

But wait! We can tell the compiler to run these in parallel:

import Data.List

import Control.Parallel

big = [1..10000000]

sum' = foldl' (+) 0

average' xs =

let s = sum' xs

l = length xs

in s `par` l `par` fromIntegral s / fromIntegral l

main = print (average big)

And lo and behold, the space leak goes away (don’t forget to compile with -threaded and run with at least -N2. With the power of multiple threads, both operations can run at the same time, and thus there is no unnecessary retention.

It is perhaps not too surprising that par can plug space leaks, given that seq can do so too. But seq has denotational content; par does not, and indeed, does nothing when you are single-threaded. This makes this solution very fragile: at runtime, we may or may not decide to evaluate the other thunk in parallel depending on core availability. But we can still profitably use par in a single-threaded context, if it can manage pre-emptive switching between two consumers of a stream. This would be a pretty interesting primitive to have, and it would also be interesting to see some sort of semantics which makes clear the beneficial space effects of such a function. Another unbaked idea is that we already have a notion of good producers and consumers for stream fusion. It doesn’t seem like too far a stretch that we could use this analysis to determine when consumers could be merged together, improving space usage.

July 13, 2011This one’s for the MIT crowd. This morning, I finished my Facebook module for BarnOwl to my satisfaction (my satisfaction being asynchronous support for Facebook API calls, i.e. no more random freezing!) Getting it to run on Linerva was a bit involved, however, so here is the recipe.

- Setup a local CPAN installation using the instructions at sipb.mit.edu, using

local::lib. Don’t forget to add the setup code to .bashrc.mine, not .bashrc, and then source them. Don’t forget to follow prerequisites: otherwise, CPAN will give a lot of prompts. - Install all of the CPAN dependencies you need. For the Facebook module, this means

Facebook::Graph and AnyEvent::HTTP. I suggest using notest, since Any::Moose seems to fail a harmless test on Linerva. Facebook::Graph fails several tests, but don’t worry about it since we’ll be using a pre-packaged version. If you want to use other modules, you will need to install them in CPAN as well. - Clone BarnOwl to a local directory (

git clone git://github.com/ezyang/barnowl.git barnowl), ./autogen.sh, configure and make. - Run using

./barnowl, and then type the command :facebook-auth and follow the instructions!

Happy Facebooking!

Postscript. I am really, really surprised that there is not a popular imperative language that has green threads and pre-emptive scheduling, allowing you to actually write code that looks blocking, although it uses an event loop under the hood. Maybe it’s because being safe while being pre-emptive is hard…

Known bugs. Read/write authentication bug has been fixed. We seem to be tickling some bugs in BarnOwl’s event loop implementation, which is causing crashing on the order of day (making it tough to debug). Keep a backup instance of BarnOwl handy.

July 11, 2011It still feels a little strange how this happened. Not a year ago, I was pretty sure I was going to do the Masters of Engineering program at MIT, to make up for a “missed year” that was spent abroad (four years at MIT plus one at Cambridge, not a bad deal.)

But a combination of conversations with various researchers whom I greatly respect, nagging from my Dad, and an inability to really figure out who I would actually do my Master’s thesis under while at MIT meant that at some point about a month and a half ago, I decided to go for the graduate school admissions cycle this fall. Oh my. It feels like undergraduate admissions all over again (which was not really a pleasant experience), though this time around, what I need to write is the “Research Statement.”

One of the reasons I blogged recently about Mendeley was because I was hoping that Mendeley would give me some insights about the kinds of papers I found interesting, and would let me easily figure out the affiliations of those researchers. (Oops, not quite there yet.) Actually, a conversation with Simon Marlow was much more fruitful: I’m currently actively looking into Ramsey (Tufts), Morrisett (Harvard), Harper (CMU), Pierce/Weirich (UPenn) and Mazieres (Stanford). Of course, I can’t help but think that I’ve missed some key players around topics that I regularly discuss on my blog, so if any of you have some ideas, please do shout out.

The process (well, what little of it I’ve started) has been quite bipolar. I frequently switch between thinking, “Oh, look at this grad student, he didn’t start having any publications till he started grad school—so I’m OK for not having any either” to “Wow, this person had multiple papers out while an undergraduate, solved multiple open problems with his thesis, and won an NSF fellowship—what am I supposed to do!” I’m still uncertain as to whether or not I’m cut out to do research—it’s certainly not for everyone. But I do know I greatly enjoyed the two times I worked at industrial research shops, and I do know that I love teaching, and I definitely know I do not want a conventional industry job. Grad school it is.

July 8, 2011I recently concluded a year long study-abroad program at the University of Cambridge. You can read my original reasons and first impressions here.

It is the Sunday before the beginning of exams, and the weather is spectacular. Most students (except perhaps the pure historians) are dourly inside, too busy revising to take advantage of it. But I am thrust out of my den, constructed of piles of notes and past exam questions, in order to go to one final revision with our history supervisor, Mirjam. I cycle down Grange road, park my bicycle outside Ridley Hall, and am greeted to a pleasant surprise: Mirjam has elected to hold the revision outside on a cluster of park benches flanked everywhere by grass and trees, and has brought a wickerbasket containing fresh fruit, small cupcakes and other treats, and also sparkling wine and beer (perhaps not the best drink for what is ostensibly a revision, but we avail ourselves of it anyway.)

History and Philosophy of Science is a course made of two strands. They start off relatively distinct from each other: History of Science began with Galileo and the dawn of the 16th century, while Philosophy of Science began by analyzing the nature of causality. But by the end of the course, philosophical questions about quantification and quantum mechanics are couched heavily in terms of the histories of these sciences, and prevailing attitudes about the origins of western civilization being rooted in Greece and the mathematics of ancient Babylonia are analyzed with increasing philosophical flavor. The mixture of the two subjects work, and taking this course has been an incredibly rich experience. (At times, I even wish we had been asked to write more than one essay a week—something that would be pretty unheard of for an MIT humanities class.)

It was also hard work. Especially in history, where my initial essays had a rocky start due to my misunderstanding of how I was supposed to be synthesizing material from a broader range of materials than just the survey texts that were required reading (I might have been a “little” negligent doing all of the required reading.) Writing HPS essays required me to block out large chunks of my time during the weekend for them; I rarely stayed up late doing assigned computer science work, but did so more than I would like the night an HPS essay was due. I always attempted to pay attention in lectures (some times more successfully than others—to this day I still don’t really understand the rise of the modern research university system.)

A few professors stand out in my memories. I will never forget Hasok Chang (pictured above)’s introductory lecture, where, in a digression, he explained he originally majored in Physics in Caltech, but switched to philosophy after his professors got annoyed when he asked questions like “What happened before the Big Bang?” It was his first year teaching the Philosophy of the Physical Sciences series of lectures (much to the chagrin of many students, who did not have any past exam questions to study against), but he went on to deliver an extremely solid series of engaging and informative lectures (I think they also appealed a bit to physicists who were tired of such abstract questions as the nature of causation and induction). He even invited us to a round of drinks at the nearby pub after his last lecture, where we had a lively debate about a recent topic over some beers.

Stephen John delivered an extremely lively and thought-provoking series of lectures on ethics in science. Most of his lectures left us with more questions than answers, but they were an elucidating journey into the realms of informed consent, the precautionary principle and cost-benefit analysis. (Informed consent is one of my new personal favorites: it’s an awesome example of how an enshrined medical practice is both too conservative and too liberal.) And I will always remember our supervisor, Richard Jennings (pictured below), as the perpetually smiling, moustached man whose supervisions weren’t really supervisions but rather just conversations about the topics which had been recently covered in lecture.

Among history lecturers, I have to tip my hat to Eleanor Robson, who delivered the last four lectures in history of science. I will admit: I wasn’t too keen on learning about Ancient Babylonia when I first read the syllabus, but what the lectures ended up being were a discussion about historiographical issues: how do historians come to know the “dry facts” that anyone who studied history in High School comes to know too well? In many ways, it’s astounding that we know as much as we do. It’s one of those lessons that you wish you learned earlier, even though, in the back of your head, you know that you wouldn’t have fully appreciated them earlier on.

Simon Schaffer (picture above) was also quite a character, a rather forceful individual who delivered our first set of history lectures. You can perhaps get a flavor of his style from the short BBC series The Light Fantastic, though he was perhaps a smidge more vulgar (in a good way!) when you saw him lecture in person. (“Fat. Irascible. Brilliant. Definitely a role model,” Schaffer, on Tycho Brahe.) And of course, Mirjam, our history supervisor, who persistently encouraged us to improve our essay writing.

HPS was pretty amazing. (I even tagged along to the Part II orientation event, even though I wouldn’t be eligible for it.) If you are a scientist who at all had an interest in philosophy or history (I first dipped my toe into philosophy taking “Logic and Reasoning” at CTY), I cannot recommend this program more highly. Readers of my blog may have noticed various attempts to discuss these issues on my blog—they are a bit harder to write about than some of the more technical things I discuss, but I think they are also very rewarding (and occasionally, some of my most popular writings—though in retrospect this one seems a bit Whiggish now.) It’s also fun: I managed to write an essay about Kuhnian scientific revolutions by framing it in the context of MIT Mystery Hunt. I won’t deny it: for a brief period of time, I felt like a liberal arts student. It has made me a better person, in many, many ways.

July 6, 2011I use Mendeley because it lets me easily search for papers I care about. Unfortunately, that seems to be all Mendeley has been doing for me… and that’s a damn shame. Maybe it’s because I’m an undergraduate, still dipping my toe into an ocean of academic research. Mendeley was aimed at practicing researchers, but not people like me, who are stilll aiming for breadth not depth. I can count on two hands the number of technical papers I’ve really dug into—I’m trying to figure out what it is exactly that I want to specialize in.

From this perspective, there are many, many things that Mendeley could be doing for me that it simply isn’t doing right now. And this is not purely a selfish perspective: the world of academics is a relatively small one, and I’d like to think a move towards my preferences is a move towards a larger body of potential users and customers. My request/plea/vision can be summed up as follows: Mendeley needs better metadata.

Metadata extraction has been a long standing complaint of many, many Mendeley users. One might at least partially chalk it up to the obsessive-compulsive nature of researchers: we want our metadata to be right, and having to manually fix essentially every paper we import our database creates a huge extra cost on using Mendeley.

How correct should this metadata be?

- If I search by author name, the list of papers I get should be equal in quality to that author’s listing of publications on his personal website. (Name de-duplication is pretty terrifying: Mendeley gives no indication of what permutation of a name is likely to be the right one and gives no advice about whether or not initials or full names should be preferred). As a prospective graduate student with some degree of specialization, knowing which authors I have the most papers of gives hints as to what departments I may be interested in.

- If I search by conference name, the list of papers I get should be equal in quality to the table of contents for that conference’s proceedings. Furthermore, there should be continuity over the years, so that I can search for all-time ICFP, not just 2011’s proceedings. Conferences have a notoriously large number of permutations of spellings (is it ICFP or International Conference for Functional Programming or…), and with no canonicalization keeping these straight is hopeless.

Here is something that would be really interesting to extract from papers, that is not readily available anywhere on the Internet: who funded the piece of work, and under what program! Researchers are obligated to acknowledge their funding source in a footnote or a section at the end of their paper, and access to this metadata would let me know “Who funds most of the research in this area” or “What grants should I be looking at for the next funding cycle.” This information is, of course, currently passed down as folklore from advisor to advisee. Extracting, polishing and publishing this data would be an interesting endeavor in its own right.

Papers don’t exist in a vacuum. On the trivial level, any paper is frequently accompanied by a slide deck or a recorded video of a talk—Mendely should track that. But on a deeper level, I’m sure many academics would die from loneliness if they were the only ones working in their field. There is a person behind the paper, and there is more information about them than just what papers they have published. What organization are they are part of? (A prospective grad student would love to know if they are faculty at a particular university.) What organization were they a part of when they published the paper? Who tends to collaborate with who—are there cliques of academics? Who was a member of the panel for what conferences?

One critical component of this is the citations of papers. Existing paper databases have concluded that this curation problem is just too hard: they simply publish plain text extracts of the reference sections. But here is a perfect opportunity to harness the power of the social Internet. Wikify the damn metadata, and let academics with an interest in this sector of academia create the mythical hyperlinked web of papers. When I can browse papers like I can browse Wikipedia will be a happy day. No paper exists in a vacuum.

Mendeley does a great job letting you attach metadata to a specific paper, which is searchable but not much else. But there are plenty of small chunks of information that could be profitably converted into generalized schemes. For example, Mendeley currently stores a bit indicating whether or not a paper is “read” or not. This is woefully insufficient: one does not simply read an academic paper (nor does one simply walk into Mordor). Maybe you’ve read the abstract, maybe you’ve skimmed the paper, maybe the paper is one that you are actively attempting to understand as part of some of your research. This workflow should be made first-class and the relevant user interface for it exposed. This information is also important if you’re trying to draw inferences about your paper reading habits from Mendeley’s database: papers you’ve imported but never looked at probably shouldn’t be counted.

In many ways, this is the call for the equivalent of the “Semantic Web” for academic papers. By in large, we are still attempting to realize this vision for the Internet at large. But there are good reasons to believe that the world of academic papers may be different. For one thing, the web of academic papers has not even reached the point of the traditional Internet: it doesn’t have hyperlinks! Additionally, academic papers are much slower moving than traditional web content and far more permanent. I want there to be no reason for my friends in industry to complain that they’d much rather a researcher publish a blog post rather than a paper. It’s ambitious, I know. But that’s my vision for Mendeley.

July 4, 2011

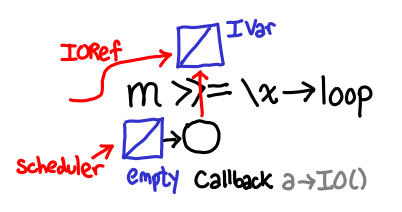

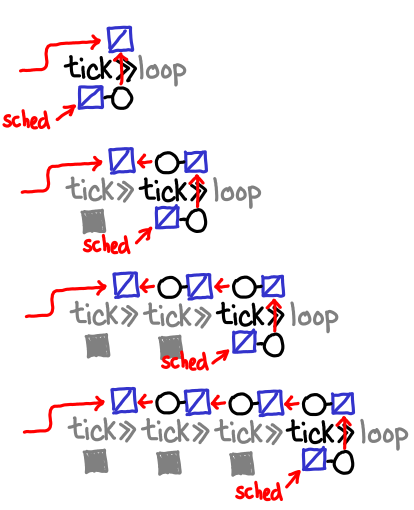

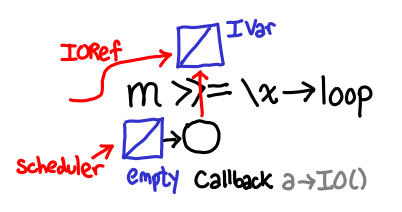

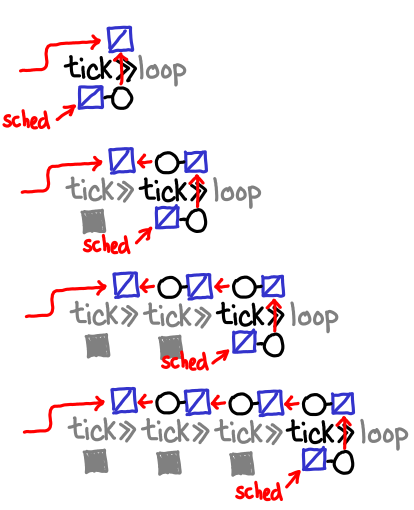

The first thing to convince yourself of is that there actually is a problem with the code I posted last week. Since this is a memory leak, we need to keep track of creations and accesses of IVars. An IVar allocation occurs in the following cases for our example:

- Invocation of

return, which returns a full IVar, - Invocation of

tick, which returns an empty IVar and schedules a thread to fill this IVar, and - Invocation of

>>=, which returns an empty IVar and a reference to this IVar in the callback attached to the left-hand IVar.

An IVar access occurs when we dereference an IORef, add a callback or fill the IVar. This occurs in these cases:

- Invocation of

>>=, which dereferences the left IVar and adds a callback, - Invocation of the callback on the left argument of

>>=, which adds a callback to the result of f x, - Invocation of the callback on the result of

f x (from the above callback), which fills the original IVar allocated in (3), and - Invocation of the scheduled thread by

tick, which fills the empty IVar it was scheduled with.

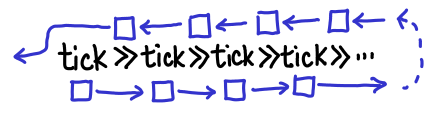

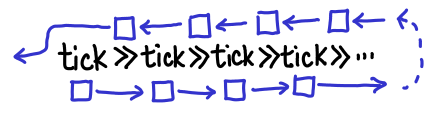

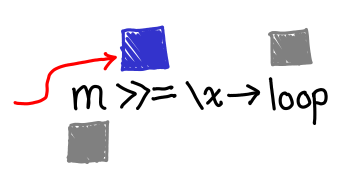

We can now trace the life-cycle of an IVar allocated by the >>= in the code loop = tick >>= loop.

IVar allocated by >>=. Two references are generated: one in the callback attached to tick and one returned.

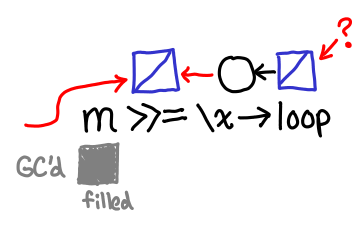

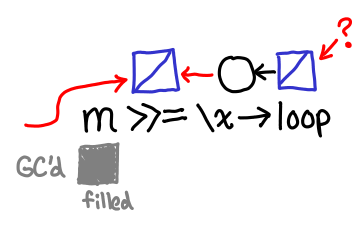

Scheduler runs thread that fills in IVar from tick, its callback is run. IVar is reachable via the newly allocated callback attached to f x. Note that f in this case is \() -> loop, so at this point the recursive call occurs.

Scheduler runs thread that fills in IVar from f x, its callback is run. IVar is filled in, and the reference to it in the callback chain is now dead. Life of the IVar depends solely on the reference that we returned to the client.

Notice that across the first and second scheduler rounds, the bind-allocated IVar is kept alive by means other than the reference we returned to the client. In the first case it’s kept alive by the callback to tick (which is in turn kept alive by its place in the execution schedule); in the second case it’s kept alive by the callback to f x. If we can get to the third case, everything will manage to get GC’d, but that’s a big if: in our infinite loop, f x is never filled in.

Even if it does eventually get filled in, we build up an IVar of depth the length of recursion, whereas if we had some sort of “tail call optimization”, we could immediately throw these IVars away.