November 25, 2012Joe Zimmerman recently shared with me a cool new way of thinking about various encryption schemes called functional encryption. It’s expounded upon in more depth in a very accessible recent paper by Dan Boneh et al.. I’ve reproduced the first paragraph of the abstract below:

We initiate the formal study of functional encryption by giving precise definitions of the concept and its security. Roughly speaking, functional encryption supports restricted secret keys that enable a key holder to learn a specific function of encrypted data, but learn nothing else about the data. For example, given an encrypted program the secret key may enable the key holder to learn the output of the program on a specific input without learning anything else about the program.

Quite notably, functional encryption generalizes many existing encryption schemes, including public-key encryption, identity-based encryption and homomorphic encryption. Unfortunately, there are some impossibility results for functional encryption in general in certain models of security (the linked paper has an impossibility result for the simulation model.) There’s no Wikipedia page for functional encryption yet; maybe you could write it!

Apropos of nothing, a math PhD friend of mine recently asked me, “So, do you think RSA works?” I said, “No, but probably no one knows how to break it at the moment.” I then asked him why the question, and he mentioned he was taking a class on cryptography, and given all of the assumptions, he was surprised any of it worked at all. To which I replied, “Yep, that sounds about right.”

November 20, 2012Functions are awesome. What if we made a PL that only had functions?

Objects are awesome. What if we made a PL where everything was an object?

Lazy evaluation is awesome. What if we made a PL where every data type was lazy?

Extremist programming (no relation to extreme programming) is the act of taking some principle, elevating it above everything else and applying it everywhere. After the dust settles, people often look at this extremism and think, “Well, that was kind of interesting, but using X in Y was clearly inappropriate. You need to use the right tool for the job!”

Here’s the catch: sometimes you should use the wrong tool for the job—because it might be the right tool, and you just don’t know it yet. If you aren’t trying to use functions everywhere, you might not realize the utility of functions that take functions as arguments [1] or cheap lambdas [2]. If you aren’t trying to use objects everywhere, you might not realize that both integers [3] and the class of an object [4] are also objects. If you aren’t trying to use laziness everywhere, you might not realize that purity is an even more important language feature [5].

This leads to two recommendations:

- When learning a new principle, try to apply it everywhere. That way, you’ll learn more quickly where it does and doesn’t work well, even if your initial intuitions about it are wrong. (The right tool for the job, on the other hand, will lead you to missed opportunities, if you don’t realize that the principle is applicable in some situation).

- When trying to articulate the essence of some principle, an extremist system is clearest. If you want to know what it is like to program with lazy evaluation, you want to use Haskell, not a language with optional laziness. Even if the extremist system is less practical, it really gets to the core of the issue much more quickly.

There are a lot of situations where extremism is inappropriate, but for fun projects, small projects and research, it can really teach you a lot. One of the most memorable interactions I had in the last year was while working with Adam Chlipala. We were working on some proofs in Coq, and I had been taking the moderate route of doing proofs step-by-step first, and then with Ltac automation once I knew the shape of the proof. Adam told me: “You should automate the proofs from the very beginning, don’t bother with the manual exploration.” [6] It was sage advice that made my life a lot better: I guess I just wasn’t extremist enough!

Files are awesome. What if we made an OS where everything was a file?

Cons cells are awesome. What if we made a PL where everything was made of cons cells?

Mathematics is awesome. What if we made a PL where everything came from math?

Arrays are awesome. What if we made a PL where everything was an array?

[1] Higher-order functions and combinators: these tend to not see very much airplay because they might be very verbose to write, or because the language doesn’t have a very good vocabulary for saying what the interface of a higher-order function is. (Types help a bit here.)

[2] Cheap lambdas are necessary for the convenient use of many features, including: monads, scoped allocation (and contexts in general), callbacks, higher-order functions.

[3] Consider early versions of Java prior to the autoboxing of integer and other primitive types.

[4] Smalltalk used this to good effect, as does JavaScript.

[5] This is one of my favorite narratives about Haskell, it comes from Simon Peyton Jones’ presentation Wearing the hair shirt (in this case, laziness).

[6] This is the essence of the Chlipala school of Coq proving, in recognition of how astonishingly easy it is to trick experienced computer scientists into writing the equivalents of straight-line programs by hand, without any abstractions.

November 8, 2012“Everything is a file.” [1] This was the design philosophy taken to its logical extreme in Plan 9. Any interface you could imagine was represented as a file. Network port, pixel buffers, kernel interfaces—all were unified under a common API: the file operations (open, read, write…) Plan 9 used this to eliminate most of its system calls: it had only thirty-nine, in contrast to modern Linux’s sprawling three hundred and twenty-six.

When I first heard of Plan 9, my first thought was, “But that’s cheating, right?” After all, they had reduced the number of syscalls but increased the number of custom files: complexity had merely been shifted around. But one of my labmates gave me a reason why this was still useful: per-process mountpoints. These mountpoints meant that I could give each process their own view of the filesystem—usually the same, but sometimes with some vital differences. Suppose that I wanted to tunnel the network connection of one of my applications: this application would be accessing the network through some file, so I instead could mount a network filesystem to the network files of another system, and transparently achieve proxying without any cooperation from my application. [2]

Let’s step back for a moment and put on our programming language hats. Suppose that a file is an abstract data type, and the syscall interface for manipulating files is the interface for this data type. What are mounts, in this universe? Another friend of mine pointed out the perfectly obvious analogy:

Files : Mounts :: Abstract Data Types : Dependency Injection

In particular, the mount is a mechanism for modifying some local namespace, so that when a file is requested, it may be provided by some file system completely different to what the process might have expected. Similarly, dependency injection specifies a namespace, such that when an object is requested, the concrete implementation may be completely different to what the caller may have expected.

The overall conclusion is that when developers implemented dependency injection, they were reimplementing Plan 9’s local mounts. Is your dependency injection hierarchical? Can you replace a hierarchy (MREPL), or mount your files before (MBEFORE) or after (MAFTER) an existing file system? Support runtime changes in the mount? Support lexical references (e.g. dot-dot ..) between entities in the hierarchy? I suspect that existing dependency injection frameworks could learn a bit from the design of Plan 9. And in Haskell, where it seems that people are able to get much further without having to create a dependency injection framework, do these lessons map back to the design of a mountable file system? I wonder.

[1] Functional programmers might be reminded of a similar mantra, “Everything is a function.”

[2] For the longest time, Linux did not provide per-process mount namespaces, and even today this feature is not available to unprivileged users—Plan 9, in contrast, had this feature available from the very beginning to all users. There is also the minor issue where per-process mounts are actually a big pain to work with in Linux, primarily, I dare say, due to the lack of appropriate tools to assist system administrators attempting to understand their applications.

November 2, 2012I’m taking a Data Visualization course this fall, and one of our assignments was to create an interactive visualization. So I thought about the problem for a little bit, and realized, “Hey, wouldn’t it be nice if we had a version of hp2ps that was both interactive and accessible from your browser?” (hp2any fulfills this niche partially, but as a GTK application).

A week of hacking later: hp/D3.js, the interactive heap profile viewer for GHC heaps. Upload your hp files, share them with friends! Our hope is that the next time you need to share a heap profile with someone, instead of running hp2ps on it and sending your colleague the ps file, you’ll just upload the hp file here and send a colleague your link. We’ve tested it on recent Firefox and Chrome, it probably will work on any sufficiently modern browser, it definitely won’t work with Internet Explorer.

Some features:

- You can annotate data points by clicking on the graph and filling in the text box that appears. These annotations are saved and will appear for anyone viewing the graph.

- You can filter heap elements based on substring match by typing in the “filter” field.

- You can drill down into more detail by clicking on one of the legend elements. If you click

OTHER, it will expand to show you more information about the heap elements in that band. You can then revert your view by pressing the Back button.

Give it a spin, and let me know about any bugs or feature suggestions! (Some known bugs: sometimes Yesod 500s, just refresh until it comes up. Also, we lack backwards animations, axis changing is a little choppy and you can’t save annotations on the OTHER band.)

October 24, 2012October has come, and with it, another Ubuntu release (12.10). I finally gave in and reinstalled my system as 64-bit land (so long 32-bit), mostly because graphics were broken on my upgraded system. As far as I could tell, lightdm was dying immediately after starting up, and I couldn’t tell where in my copious configuration I had messed it up. I also started encrypting my home directory.

- All fstab mount entries now show up in Nautilus. The correct fix appears to be not putting these mounts in

/media, /mnt or /home/, and then they won’t be picked up. - Fonts continue to be an exquisite pain in rxvt-unicode. I had to switch from

URxvt.letterSpace: -1 to URxvt.letterSpace: -2 to keep things working, and the fonts still look inexplicably different. (I haven’t figured out why, but the new world order isn’t a complete eyesore so I’ve given up for now.) There’s also a patch which fixes this problem (hat tip this libxft2 bug bug) but I found that at least for DejaVu the letterSpace hack was equivalent. - When you manually suspend your laptop and close the lid too rapidly, Ubuntu also registers the close laptop event, so when you resume, it will re-suspend! Fortunately, this is pretty harmless; if you press the power-button again, it will resume properly. You can also work around this by turning off resume on close lid in your power settings.

- On resume, the network manager applet no longer accurately reflects what network you are connected to (it thinks you’re connected, but doesn’t know to what, or what signal strength it is). It’s mostly harmless but kind of annoying; if anyone’s figured this one out please let me know!

- Hibernate continues not to work, though I haven’t tried too hard to get it working.

- Firefox was being really slow, so I reset it. And then it was fast again. Holy smoke! Worth a try if you’ve found Firefox to be really slow.

- GHC is now 7.4.2, so you’ll need to rebuild. “When do we get our 7.6 shinies!”

My labmates continue to tease me for not switching to Arch. We’ll see…

October 22, 2012I was wandering through the Gates building when the latest issue of the ACM XRDS, a student written magazine, caught my eye.

“Oh, didn’t I write an article for this issue?” Yes, I had!

The online version is here, though I hear it’s behind a paywall, so I’ve copypasted a draft version of the article below. Fun fact: The first version of this article had a Jeff Dean fact, but we got rid of it because we weren’t sure if everyone knew what Jeff Dean facts were…

True fact: as a high school student, Jeff Dean wrote a statistics package that, on certain functions, was twenty-six times faster than equivalent commercial packages. These days, Jeff Dean works at Google, helping architect and optimize some of the biggest data-crunching systems Google employs on a day-to-day basis. These include the well known MapReduce (a programming model for parallelizing large computations) and BigTable (a system which stores almost all of Google’s data). Jeff’s current project is infrastructure for deep learning via neural networks, a system with applications for speech/image recognition and natural language processing.

While Jeff has become a public face attached to much of Google’s internal infrastructure projects, Jeff stresses the fact that these projects require a mix of areas of expertise from people. Any given project might have people with backgrounds in networking, machine learning and distributed systems. Collectively, a project can achieve more than any person individually. The downsides? With all of the different backgrounds, you really need to know when to say: “Hold on, I don’t understand this machine learning term.” Jeff adds, however, that working on these teams is lots of fun: you get to learn about a sub-domain you might not have known very much about.

Along with a different style of solving problems, Google also has different research goals than academia. Jeff gave a particular example of this: when an academic is working on a system, they don’t have to worry about what happens if some really rare hardware failure occurs: they simply have to demo the idea. But Google has to worry about these corner cases; it is just what happens when one of your priorities is building a production system. There is also a tension with releasing results to the general public. Before the publication of the MapReduce paper, there was an internal discussion about whether or not to publish. Some were concerned that the paper could benefit Google’s competitors. In the end, though, Google decided to release the paper, and you can now get any number of open source implementations of MapReduce.

While Jeff has been at Google for over a decade, the start of his career looked rather different. He recounts how he ended up getting his first job. “I moved around a lot as a kid: I went to eleven schools in twelve years in lots of different places in the world… We moved to Atlanta after my sophomore year in high school, and in this school, I had to do an internship before we could graduate… I knew I was interested in developing software. So the guidance counselor of the school said, ‘Oh, great, I’ll set up something’, and she set up this boring sounding internship. I went to meet with them before I was going to start, and they essentially wanted me to load tapes into tape drives at this insurance company. I thought, ‘That doesn’t sound much like developing software to me.’ So, I scrambled around a bit, and ended up getting an internship at the Center for Disease Control instead.”

This “scrambled” together internship marked the beginning of many years of work for the CDC and the World Health Organization. First working at Atlanta, and then at Geneva, Jeff spent a lot of time working on what progressively grew into a larger and larger system for tracking the spread of infectious disease. These experiences, including a year working full-time between his graduation from undergraduate and his arrival at graduate school, helped fuel is eventual choice of a thesis topic: when Jeff took an optimizing compilers course, he wondered if he could teach compilers to do the optimizations he had done at the WHO. He ended up working with Craig Chambers, a new faculty member who had started the same year he started as a grad student. “It was great, a small research group of three or four students and him. We wrote this optimizing compiler from scratch, and had fun and interesting optimization work.” When he finished his PhD thesis, he went to work at Digital Equipment Corporation and worked on low-level profiling tools for applications.

Jeff likes doing something different every few years. After working on something for a while, he’ll pick an adjacent field and then learn about that next. But Jeff was careful to emphasize the fact that while this strategy worked for him, he also thought it was important to have different types of researchers, to have people who were willing to work on the same problem for decades, or the entire career—these people have a lot of in depth knowledge in this area. “There’s room in the world for both kinds of people.” But, as he has moved from topic to topic, it turns out that Jeff has come back around again: his current project at Google on parallel training of neural networks was the topic of Jeff’s undergraduate senior thesis. “Ironic,” says Jeff.

October 19, 2012This post is the spiritual predecessor to Flipping Burgers in coBurger King.

What does it mean for something to be dual? A category theorist would say, “It’s the same thing, but with all the arrows flipped around.” This answer seems frustratingly vague, but actually it’s quite precise. The only thing missing is knowing what arrows flip around! If you know the arrows, then you know how to dualize. In this post, I’d like to take a few structures that are well known to Haskellers, describe what the arrows for this structure look like, and then show that when we flip the arrows, we get a dual concept.

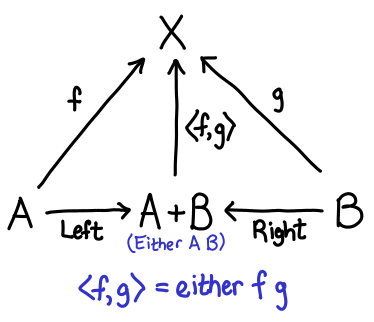

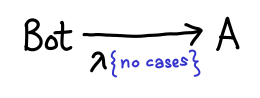

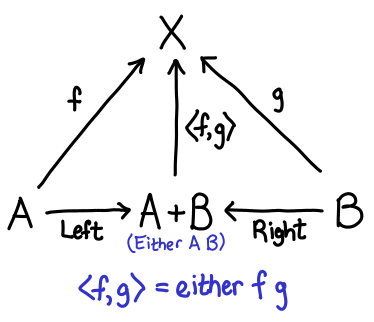

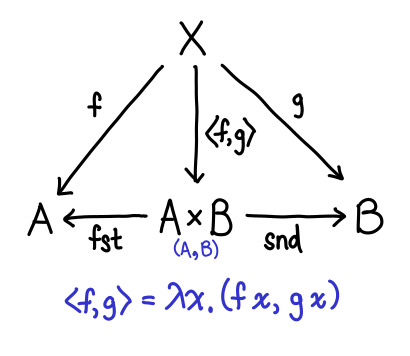

Suppose you have some data of the type Either a b. With all data, there are two fundamental operations we would like to perform on them: we’d like to be able to construct it and destruct it. The constructors of Either are the Left :: a -> Either a b and Right :: b -> Either a b, while a reasonable choice of destructor might be either :: (a -> r) -> (b -> r) -> Either a b -> r (case analysis, where the first argument is the Left case, and the second argument is the Right case). Let’s draw a diagram:

I’ve added in two extra arrows: the represent the fact that either f g . Left == f and either f g . Right == g; these equations in some sense characterize the relationship between the constructor and destructor.

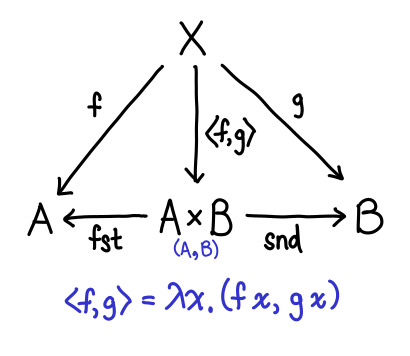

OK, so what happens when we flip these arrows around? The title of this section has given it away, but let’s look at it:

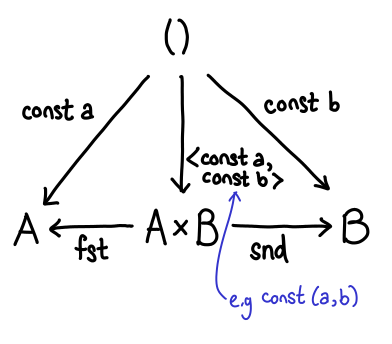

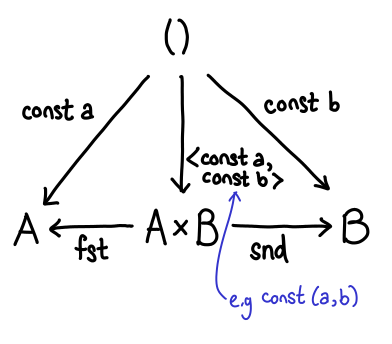

Some of these arrows are pretty easy to explain. What used to be our constructors (Left and Right) are now our destructors (fst and snd). But what of f and g and our new constructor? In fact, \x -> (f x, g x) is in some sense a generalized constructor for pairs, since if we set f = const a and g = const b we can easily get a traditional constructor for a pair (where the specification of the pair itself is the arrow—a little surprising, when you first see it):

So, sums and products are dual to each other. For this reason, sums are often called coproducts.

(Keen readers may have noticed that this presentation is backwards. This is mostly to avoid introducing \x -> (f x, g x), which seemingly comes out of nowhere.)

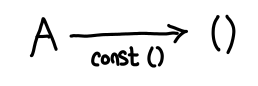

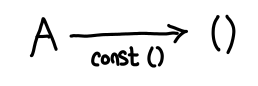

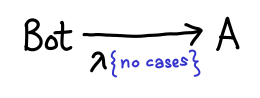

The unit type (referred to as top) and the bottom type (with no inhabitants) exhibit a duality between one another. We can see this as follows: for any Haskell type, I can trivially construct a function which takes a value of that type and produces unit; it’s const ():

Furthermore, ignoring laziness, this is the only function which does this trick: it’s unique. Let’s flip these arrows around: does there exist a type A for which for any type B, there exists a function A -> B? At first glance, this would seem impossible. B could be anything, including an uninhabited type, in which case we’d be hard pressed to produce anything of the appropriate value. But wait: if A is uninhabited, then I don’t have to do anything: it’s impossible for the function to be invoked!

Thus, top and bottom are dual to one another. In fact, they correspond to the concepts of a terminal object and an initial object (respectively) in the category Hask.

One important note about terminal objects: is Int a terminal object? It is certainly true that there are functions which have the type forall a. a -> Int (e.g. const 2). However, this function is not unique: there’s const 0, const 1, etc. So Int is not terminal. For good reason too: there is an easy to prove theorem that states that all terminal objects are isomorphic to one another (dualized: all initial objects are isomorphic to one another), and Int and () are very obviously not isomorphic!

One of the most important components of a functional programming language is the recursive data structure (also known as the inductive data structure). There are many ways to operate on this data, but one of the simplest and most well studied is the fold, possibly the simplest form a recursion one can use.

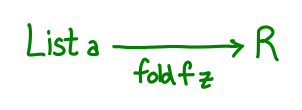

The diagram for a fold is a bit involved, so we’ll derive it from scratch by thinking about the most common fold known to functional programmers, the fold on lists:

data List a = Cons a (List a) | Nil

foldr :: (a -> r -> r) -> r -> List a -> r

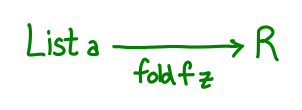

The first two arguments “define” the fold, while the third argument simply provides the list to actually fold over. We could try to draw a diagram immediately:

But we run into a little bit of trouble: our diagram is a bit boring, mostly because the pair (a -> r -> r, r) doesn’t really have any good interpretation as an arrow. So what are we to do? What we’d really like is a single function which encodes all of the information that our pair originally encoded.

Well, here’s one: g :: Maybe (a, r) -> r. Supposing we originally had the pair (f, z), then define g to be the following:

g (Just (x, xs)) = f x xs

g Nothing = z

Intuitively, we’ve jammed the folding function and the initial value into one function by replacing the input argument with a sum type. To run f, we pass a Just; to get z, we pass a Nothing. Generalizing a bit, any fold function can be specified with a function g :: F a r -> r, where F a is a functor suitable for the data type in question (in the case of lists, type F a r = Maybe (a, r).) We reused Maybe so that we didn’t have to define a new data type, but we can rename Just and Nothing a little more suggestively, as data ListF a r = ConsF a r | NilF. Compared to our original List definition (Cons a (List a) | Nil), it’s identical, but with all the recursive occurrences of List a replaced with r.

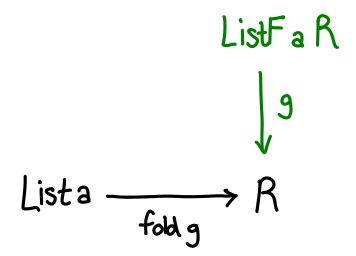

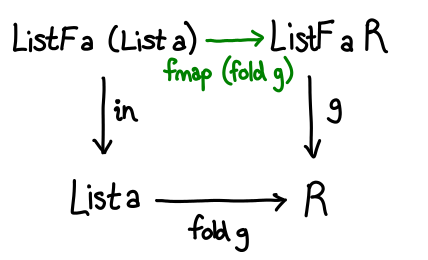

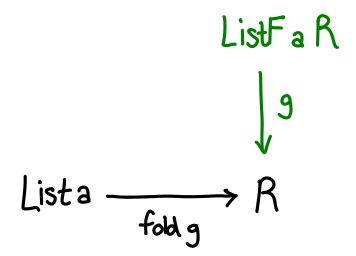

With this definition in hand, we can build out our diagram a bit more:

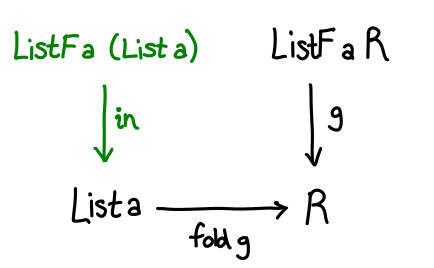

The last step is to somehow relate List a and ListF a r. Remember how ListF looks a lot like List, just with r replacing List a. So what if we had ListF a (List a)—literally substituting List a back into the functor. We’d expect this to be related to List a, and indeed there’s a simple, unique function which converts one to the other:

in :: ListF a (List a) -> List a

in (ConsF x xs) = Cons x xs

in NilF = Nil

There’s one last piece to the puzzle: how do we convert from ListF a (List a) to ListF a r? Well, we already have a function fold g :: List a -> r, so all we need to do is lift it up with fmap.

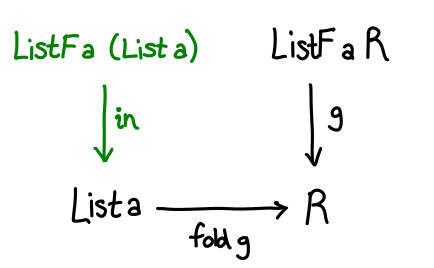

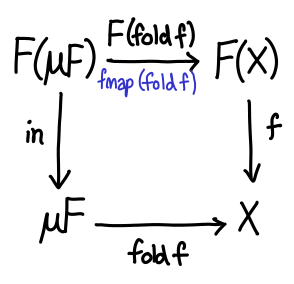

We have a commuting diagram, and require that g . fmap (fold g) = fold g . in.

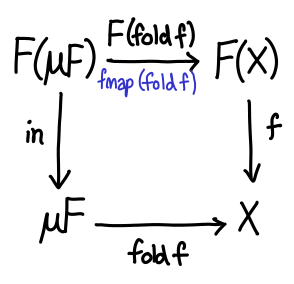

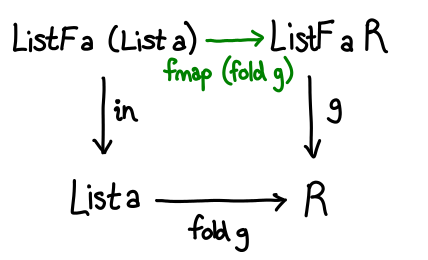

All that’s left now is to generalize. In general, ListF and List are related using little trick called the Mu operator, defined data Mu f = Mu (f (Mu f)). Mu (ListF a) is isomorphic to List a; intuitively, it replaces all instances of r with the data structure you are defining. So in general, the diagram looks like this:

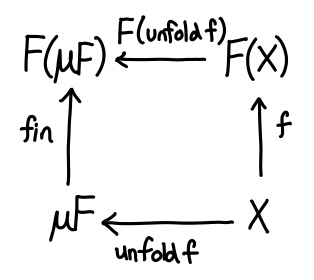

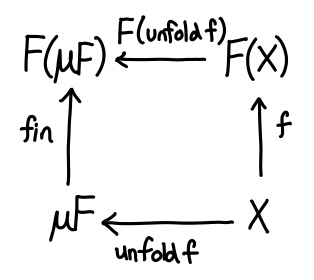

Now that all of these preliminaries are out of the way, let’s dualize!

If we take a peek at the definition of unfold in Prelude: unfold :: (b -> Maybe (a, b)) -> b -> [a]; the Maybe (a, b) is exactly our ListF!

The story here is quite similar to the story of sums and products: in the recursive world, we were primarily concerned with how to destruct data. In the corecursive world, we are primarily concerned with how to construct data: g :: r -> F r, which now tells us how to go from r into a larger Mu F.

Dualization is an elegant mathematical concept which shows up everywhere, once you know where to look for it! Furthermore, it is quite nice from the perspective of a category theorist, because when you know two concepts are dual, all the theorems you have on one side flip over to the other side, for free! (This is because all of the fundamental concepts in category theory can be dualized.) If you’re interested in finding out more, I recommend Dan Piponi’s article on data and codata.

October 16, 2012This post is adapted from the talk which Deian Stefan gave for Hails at OSDI 2012.

It is a truth universally acknowledged that any website (e.g. Facebook) is in want of a web platform (e.g. the Facebook API). Web platforms are awesome, because they allow third-party developers to build apps which operate on our personal data.

But web platforms are also scary. After all, they allow third-party developers to build apps which operate on our personal data. For all we know, they could be selling our email addresses to spamlords or snooping on our personal messages. With the ubiquity of third-party applications, it’s nearly trivial to steal personal data. Even if we assumed that all developers had our best interests at heart, we’d still have to worry about developers who don’t understand (or care about) security.

When these third-party applications live on untrusted servers, there is nothing we can do: once the information is released, the third-party is free to do whatever they want. To mitigate this, platforms like Facebook employ a CYA (“Cover Your Ass”) approach:

The thesis of the Hails project is that we can do better. Here is how:

First, third-party apps must be hosted on a trusted runtime, so that we can enforce security policies in software. At minimum, this means we need a mechanism for running untrusted code and expose trusted APIs for things like database access. Hails uses Safe Haskell to implement and enforce such an API.

Next, we need a way of specifying security policies in our trusted runtime. Hails observes that most data models have ownership information built into the objects in question. So a policy can be represented as a function on a document to a set of labels of who can read and a set of labels of who can write. For example, the policy “only Jen’s friends may see her email addresses” is a function which takes the a document representing a user, and returns the “friends” field of the document as the set of valid readers. We call this the MP of an application, since it combines both a model and a policy, and we provide a DSL for specifying policies. Policies tend to be quite concise, and more importantly are centralized in one place, as opposed to many conditionals strewn throughout a codebase.

Finally, we need a way of enforcing these security policies, even when untrusted code is being run. Hails achieves this by implementing thread-level dynamic information flow control, taking advantage of Haskell’s programmable semicolon to track and enforce information flow. If a third-party application attempts to share some data with Bob, but the data is not labeled as readable by Bob, the runtime will raise an exception. This functionality is called LIO (Labelled IO), and is built on top of Safe Haskell.

Third-party applications run on top of these three mechanisms, implementing the view and controller (VC) components of a web application. These components are completely untrusted: even if they have security vulnerabilities or are malicious, the runtime will prevent them from leaking private information. You don’t have to think about security at all! This makes our system a good choice even for implementing official VCs.

One of the example applications we developed was GitStar, a website which hosts Git projects in much the same way as GitHub. The key difference is that almost all of the functionality in GitStar is implemented in third party apps, including project and user management, code viewing and the wiki. GitStar simply provides MPs (model-policy) for projects and users. The rest of the components are untrusted.

Current web platforms make users decide between functionality and privacy. Hails lets you have your cake and eat it too. Hails is mature enough to be used in a real system; check it out at http://www.gitstar.com/scs/hails or just cabal install hails.

October 15, 2012So you’re half bored to death working on your propositional logic problem set (after all, you know what AND and OR are, being a computer scientist), and suddenly the problem set gives you a real stinker of a question:

Is it true that Γ ⊢ A implies that Γ ⊢ ¬A is false?

and you think, “Double negation, no problem!” and say “Of course!” Which, of course, is wrong: right after you turn it in, you think, “Aw crap, if Γ contains a contradiction, then I can prove both A and ¬A.” And then you wonder, “Well crap, I have no intuition for this shit at all.”

Actually, you probably already have a fine intuition for this sort of question, you just don’t know it yet.

The first thing we want to do is establish a visual language for sentences of propositional logic. When we talk about a propositional sentence such as A ∨ B, there are some number of propositional variables which need assignments given to them, e.g. A is true, B is false. We can think of these assignments as forming a set of size 2^n, where n is the number of propositional variables being considered. If n were small, we could simply draw a Venn diagram, but since n could be quite big we’ll just visualize it as a circle:

We’re interested in subsets of assignments. There are lots of ways to define these subsets; for example, we might consider the set of assignments where A is assigned to be true. But we’ll be interested in one particular type of subset: in particular, the subset of assignments which make some propositional sentence true. For example, “A ∨ B” corresponds to the set {A=true B=true, A=true B=false, A=false B=true}. We’ll draw a subset graphically like this:

Logical connectives correspond directly to set operations: in particular, conjunction (AND ∧) corresponds to set intersection (∩) and disjunction (OR ∨) corresponds to set union (∪). Notice how the corresponding operators look very similar: this is not by accident! (When I was first learning my logical operators, this is how I kept them straight: U is for union, and it all falls out from there.)

Now we can get to the meat of the matter: statements such as unsatisfiability, satisfiability and validity (or tautology) are simply statements about the shape of these subsets. We can represent each of these visually: they correspond to empty, non-empty and complete subsets respectively:

This is all quite nice, but we haven’t talked about how the turnstile (⊢) aka logical entailment fits into the picture. In fact, when I say something like “B ∨ ¬B is valid”, what I’m actually saying is “⊢ B ∨ ¬B is true”; that is to say, I can always prove “B ∨ ¬B”, no matter what hypothesis I am permitted.”

So the big question is this: what happens when I add some hypotheses to the mix? If we think about what is happening here, when I add a hypothesis, I make life “easier” for myself in some sense: the more hypotheses I add, the more propositional sentences are true. To flip it on its head, the more hypotheses I add, the smaller the space of assignments I have to worry about:

All I need for Γ ⊢ φ to be true is for all of the assignments in Γ to cause φ to be true, i.e. Γ must be contained within φ.

Sweet! So let’s look at this question again:

Is it true that Γ ⊢ A implies that Γ ⊢ ¬A is false?

Recast as a set theory question, this is:

For all Γ and A, is it true that Γ ⊂ A implies that Γ ⊄ A^c? (set complement)

We consider this for a little bit, and realize: “No! For it is true that the empty set is a subset of all sets!” And of course, the empty set is precisely a contradiction: subset of everything (ex falso), and superset of nothing but itself (only contradiction implies contradiction).

It turns out that Γ is a set as well, and one may be tempted to ask whether or not set operations on Γ have any relationship to the set operations in our set-theoretic model. It is quite tempting, because unioning together Γ seems to work quite well: Γ ∪ Δ seems to give us the conjunction of Γ and Δ (if we interpret the sets by ANDing all of their elements together.) But in the end, the best answer to give is “No”. In particular, set intersection on Γ is incoherent: what should {A} ∩ {A ∧ A} be? A strictly syntactic comparison would say {}, even though clearly A ∧ A = A. Really, the right thing to do here is to perform a disjunction, but this requires us to say {A} ∩ {B} = {A ∨ B}, which is confusing and better left out of sight and out of mind.

October 12, 2012Jon Howell dreams of a new Internet. In this new Internet, cross-browser compatibility checking is a distant memory and new features can be unilaterally be added to browsers without having to convince the world to upgrade first. The idea which makes this Internet possible is so crazy, it just might work.

What if a web request didn’t just download a web page, but the browser too?

“That’s stupid,” you might say, “No way I’m running random binaries from the Internet!” But you’d be wrong: Howell knows how to do this, and furthermore, how to do so in a way that is safer than the JavaScript your browser regularly receives and executes. The idea is simple: the code you’re executing (be it native, bytecode or text) is not important, rather, it is the system API exposed to the code that determines the safety of the system.

Consider today’s browser, one of the most complicated pieces of software installed on your computer. It provides interfaces to “HTTP, MIME, HTML, DOM, CSS, JavaScript, JPG, PNG, Java, Flash, Silverlight, SVG, Canvas, and more”, all of which almost assuredly have bugs. The richness of the APIs are their own downfall, as far as security is concerned. Now consider what APIs a native client would need to expose, assuming that the website provided the browser and all of the libraries.

The answer is very little: all you need is a native execution environment, a minimal interface for persistent state, an interface for external network communication and an interface for drawing pixels on the screen (ala VNC). That’s it: everything else can be implemented as untrusted native code provided by the website. This is an interface that is small enough that we would have a hope of making sure that it is bug free.

What you gain from this radical departure from the original Internet is fine-grained control over all aspects of the application stack. Websites can write the equivalents of native apps (ala an App Store), but without the need to press the install button. Because you control the stack, you no longer need to work around browser bugs or missing features; just pick an engine that suits your needs. If you need push notifications, no need to hack it up with a poll loop, just implement it properly. Web standards continue to exist, but no longer represent a contract between website developers and users (who couldn’t care less about under the hood); they are simply a contract between developers and other developers of web crawlers, etc.

Jon Howell and his team have implemented a prototype of this system, and you can read more about the (many) technical difficulties faced with implementing a system like this. (Do I have to download the browser every time? How do I implement a Facebook Like button? What about browser history? Isn’t Google Native Client this already? Won’t this be slow?)

As a developer, I long for this new Internet. Never again would I have to write JavaScript or worry browser incompatibilities. I could manage my client software stack the same way I manage my server software stack, and use off-the-shelf components except in specific cases where custom software was necessary.) As a client, my feelings are more ambivalent. I can’t use Adblock or Greasemonkey anymore (that would involve injecting code into arbitrary executables), and it’s much harder for me to take websites and use them in ways their owners didn’t originally expect. (Would search engines exist in the same form in this new world order?) Oh brave new world, that has such apps in’t!