Ever wondered how Haskellers are magically able to figure out the implementation of functions just by looking at their type signature? Well, now you can learn this ability too. Let’s play a game.

You are an inventor, world renowned for your ability to make machines that transform things into other things. You are a proposer.

But there are many who would doubt your ability to invent such things. They are the verifiers.

Read more...

In 2007, Eric Kidd wrote a quite popular article named 8 ways to report errors in Haskell. However, it has been four years since the original publication of the article. Does this affect the veracity of the original article? Some names have changed, and some of the original advice given may have been a bit… dodgy. We’ll take a look at each of the recommendations from the original article, and also propose a new way of conceptualizing all of Haskell’s error reporting mechanisms.

Read more...

Consider the following data type in Haskell:

data Box a = B a

How many computable functions of type Box a -> Box a are there? If we strictly use denotational semantics, there are seven:

But if we furthermore distinguish the source of the bottom (a very operational notion), some functions with the same denotation have more implementations…

- Irrefutable pattern match:

f ~(B x) = B x. No extras. - Identity:

f b = b. No extras. - Strict:

f (B !x) = B x. No extras. - Constant boxed bottom: Three possibilities:

f _ = B (error "1"); f b = B (case b of B _ -> error "2"); and f b = B (case b of B !x -> error "3"). - Absent: Two possibilities:

f (B _) = B (error "4"); and f (B x) = B (x `seq` error "5"). - Strict constant boxed bottom:

f (B !x) = B (error "6"). - Bottom: Three possibilities:

f _ = error "7"; f (B _) = error "8"; and f (B !x) = error "9".

List was ordered by colors of the rainbow. If this was hieroglyphics to you, may I interest you in this blog post?

Read more...

As it stands, it is impossible to define certain value-strict operations on IntMaps with the current containers API. The reader is invited, for example, to try efficiently implementing map :: (a -> b) -> IntMap a -> IntMap b, in such a way that for a non-bottom and non-empty map m, Data.IntMap.map (\_ -> undefined) m == undefined.

Now, we could have just added a lot of apostrophe suffixed operations to the existing API, which would have greatly blown it up in size, but following conversation on libraries@haskell.org, we’ve decided we will be splitting up the module into two modules: Data.IntMap.Strict and Data.IntMap.Lazy. For backwards compatibility, Data.IntMap will be the lazy version of the module, and the current value-strict functions residing in this module will be deprecated.

Read more...

OCaml supports anonymous variant types, of the form type a = [`Foo of int | `Bar of bool], with the appropriate subtyping relations. Subtyping is, in general, kind of tricky, so I have been using these variant types fairly conservatively. (Even if a feature gives you too much rope, it can be manageable and useful if you use discipline.) Indeed, they are remarkably handy for one particular use-case for which I would have normally deployed GADTs. This is the “Combining multiple sum types into a single sum type” use-case.

Read more...

It is not too difficult (scroll to “Non sequitur”) to create a combinator which combines two folds into a single fold that operates on a single input list in one pass. This is pretty important if your input list is pretty big, since doing the folds separately could result in a space leak, as might be seen in the famous “average” space leak:

import Data.List

big = [1..10000000]

sum' = foldl' (+) 0

average xs = fromIntegral (sum' xs) / fromIntegral (length xs)

main = print (average big)

(I’ve redefined sum so we don’t stack overflow.) I used to think combining functions for folds were pretty modular, since they had a fairly regular interface, could be combined together, and really represented the core notion of when it was possible to eliminate such a space leak: obviously, if you have two functions that require random access to elements of the list, they’ll retain the entirety of it all the way through.

Read more...

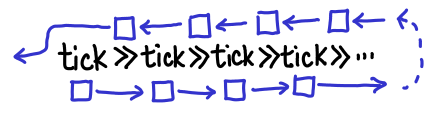

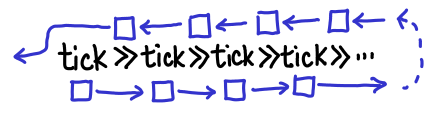

The first thing to convince yourself of is that there actually is a problem with the code I posted last week. Since this is a memory leak, we need to keep track of creations and accesses of IVars. An IVar allocation occurs in the following cases for our example:

- Invocation of

return, which returns a full IVar, - Invocation of

tick, which returns an empty IVar and schedules a thread to fill this IVar, and - Invocation of

>>=, which returns an empty IVar and a reference to this IVar in the callback attached to the left-hand IVar.

An IVar access occurs when we dereference an IORef, add a callback or fill the IVar. This occurs in these cases:

Read more...

One downside to the stupid scheduler I mentioned in the previous IVar monad post was that it would easily stack overflow, since it stored all pending operations on the stack. We can explicitly move all of these pending callbacks to the heap by reifying the execution schedule. This involves adding Schedule state to our monad (I’ve done so with IORef Schedule). Here is a only slightly more clever scheduler (I’ve also simplified some bits of code, and added a new addCallback function):

Read more...

An IVar is an immutable variable; you write once, and read many times. In the Par monad framework, we use a prompt monad style construction in order to encode various operations on IVars, which deterministic parallel code in this framework might use. The question I’m interested in this post is an alternative encoding of this functionality, which supports nondeterministic concurrency and shows up in other contexts such as Python Twisted, node.js, any JavaScript UI library and LWT. Numerous bloggers have commented on this. But despite all of the monad mania surrounding what are essentially glorified callbacks, no one actually uses this monad when it comes to Haskell. Why not? For one reason, Haskell has cheap and cheerful preemptive green threads, so we can write our IO in synchronous style in lots of threads. But another reason, which I will be exploring in a later blog post, is that naively implementing bind in this model space leaks! (Most event libraries have worked around this bug in some way or another, which we will also be investigating.)

Read more...

I recently encountered the following pattern while writing some Haskell code, and was surprised to find there was not really any support for it in the standard libraries. I don’t know what it’s called (neither did Simon Peyton-Jones, when I mentioned it to him), so if someone does know, please shout out. The pattern is this: many times an endomorphic map (the map function is a -> a) will not make very many changes to the underlying data structure. If we implement the map straight-forwardly, we will have to reconstruct the entire spine of the recursive data structure. However, if we use instead the function a -> Maybe a, we can reuse old pieces of the map if there were no changes to it. (Regular readers of my blog may recognize this situation from this post.) So what is such an alternative map (a -> Maybe a) -> f a -> Maybe (f a) called?

Read more...