Prio: Private, Robust, and Scalable Computation of Aggregate Statistics

I want to take the opportunity to advertise some new work from a colleague of mine, Henry Corrigan-Gibbs (in collaboration with the venerable Dan Boneh) on the subject of preserving privacy when collecting aggregate statistics. Their new system is called Prio and will be appearing at this year's NSDI.

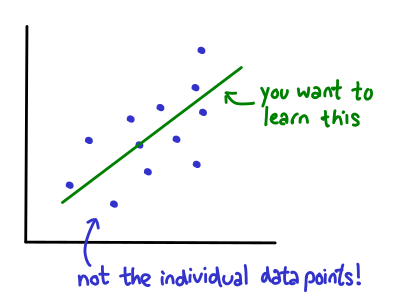

The basic problem they tackle is this: suppose you're Google and you want to collect some statistics on your users to compute some aggregate metrics, e.g., averages or a linear regression fit:

A big problem is how to collect this data without compromising the privacy of your users. To preserve privacy, you don't want to know the data of each of your individual users: you'd like to get this data in completely anonymous form, and only at the end of your collection period, get an aggregate statistic.

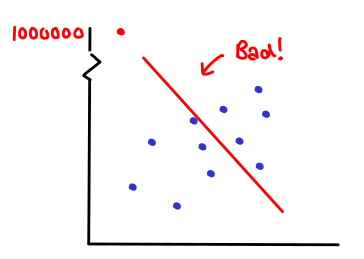

This is an old problem; there are a number of existing systems which achieve this goal with varying tradeoffs. Prio tackles one particularly tough problem in the world of private aggregate data collection: robustness in the face of malicious clients. Suppose that you are collecting data for a linear regression, and the inputs your clients send you are completely anonymous. A malicious client could send you a bad data point that could skew your entire data set; and since you never get to see the individual data points of your data set, you would never notice:

Thus, Prio looks at the problem of anonymously collecting data, while at the same time being able to validate that the data is reasonable.

The mechanism by which Prio does this is pretty cool, and so in this post, I want to explain the key insights of their protocol. Prio operates in a regime where a client secret shares their secret across a pool of servers which are assumed to be non-colluding; as long as at least one server is honest, nothing is revealed about the client's secret until the servers jointly agree to publish the aggregate statistic.

Here is the problem: given a secret share of some hidden value, how can we efficiently check if it is valid? To answer this question, we first have to explain a little bit about the world of secret sharing.

A secret sharing scheme allows you to split a secret into many pieces, so that the original secret cannot be recovered unless you have some subset of the pieces. There are amazingly simple constructions of secret sharing: suppose that your secret is the number x in some field (e.g., integers modulo some prime p), and you want to split it into n parts. Then, let the first n-1 shares be random numbers in the field, the last random number be x minus the sum of the previous shares. You reconstruct the secret by summing all the shares together. This scheme is information theoretically secure: with only n-1 of the shares, you have learned nothing about the underlying secret. Another interesting property of this secret sharing scheme is that it is homomorphic over addition. Let your shares of x and y be and

: then

form secret shares of x + y, since addition in a field is commutative (so I can reassociate each of the pairwise sums into the sum for x, and the sum for y.)

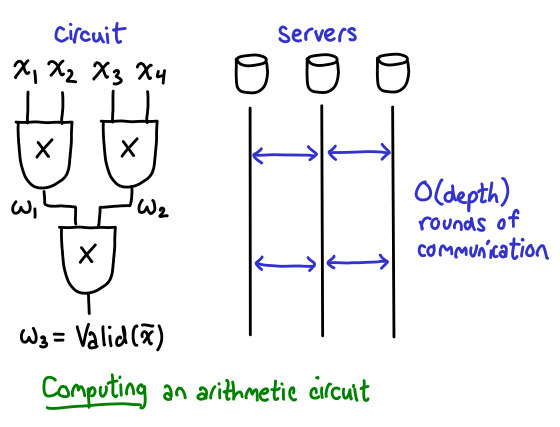

Usually, designing a scheme with homomorphic addition is easy, but having a scheme that supports addition and multiplication simultaneously (so that you can compute interesting arithmetic circuits) is a bit more difficult. Suppose you want to compute an arithmetic circuit on some a secret shared value: additions are easy, but to perform a multiplication, most multiparty computation schemes (Prio uses Beaver's MPC protocol) require you to perform a round of communication:

While you can batch up multiplications on the same "level" of the circuit, so that you only to do as many rounds as the maximum depth of multiplications in the circuit, for large circuits, you may end up having to do quite a bit of communication. Henry tells me that fully homomorphic secret sharing has been the topic of some research ongoing research; for example, this paper about homomorphic secret sharing won best paper at CRYPTO last year.

Returning to Prio, recall that we had a secret share of the user provided input, and we would like to check if it is valid according to some arithmetic circuit. As we've seen above, we could try using a multi-party computation protocol to compute shares of the output of the circuit, reveal the output of the circuit: if it says that the input is valid, accept it. But this would require quite a few rounds of communication to actually do the computation!

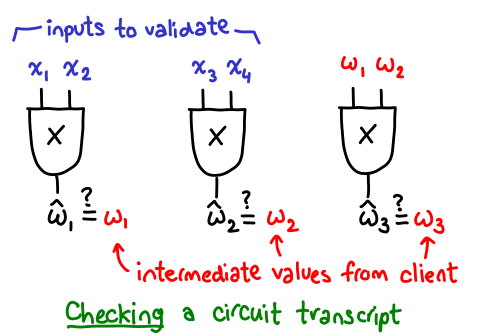

Here is one of the key insights of Prio: we don't need the servers to compute the result of the circuit--an honest client can do this just fine--we just need them to verify that a computation of the circuit is valid. This can be done by having the client ship shares of all of the intermediate values on each of the wires of the circuit, having the servers recompute the multiplications on these shares, and then comparing the results with the intermediate values provided to us by the client:

When we transform the problem from a computation problem to a verification one, we now have an embarrassingly parallel verification circuit, which requires only a single round to multiply each of the intermediate nodes of the circuit.

There is only one final problem: how are we to check that the recomputed multiplies of the shares and the client provided intermediate values are consistent? We can't publish the intermediate values of the wire (that would leak information about the input!) We could build a bigger circuit to do the comparison and combine the results together, but this would require more rounds of communication.

To solve this problem, Prio adopts an elegant trick from Ben-Sasson'12 (Near-linear unconditionally-secure multiparty computation with a dishonest minority): rather than publish the entire all of the intermediate wires, treat them as polynomials and publish the evaluation of each polynomial at a random point. If the servers behave correctly, they reveal nothing about the original polynomials; furthermore, with high probability, if the original polynomials are not equal, then the evaluation of the polynomials at a random point will also be not equal.

This is all very wonderful, but I'd like to conclude with a cautionary tale: you have to be very careful about how you setup these polynomials. Here is the pitfall: suppose that a malicious server homomorphically modifies one of their shares of the input, e.g., by adding some delta. Because our secret shares are additive, adding a delta to one of the share causes the secret to also be modified by this delta! If the adversary can carry out the rest of the protocol with this modified share, when the protocol finishes running, he finds out whether or not the modified secret was valid. This leaks information about the input: if your validity test was "is the input 0 or 1", then if you (homomorphically) add one to the input and it is still valid, you know that it definitely was zero!

Fortunately, this problem can be fixed by randomizing the polynomials, so that even if the input share is shifted, the rest of the intermediate values that it computes cannot be shifted in the same way. The details are described in the section "Why randomize the polynomials?" I think this just goes to show how tricky the design of cryptographic systems can be!

In any case, if this has piqued your interest, go read the paper! If you're at MIT, you can also go see Henry give a seminar on the subject on March 22 at the MIT CSAIL Security Seminar.