The Difference between Recursion & Induction

Recursion and induction are closely related. When you were first taught recursion in an introductory computer science class, you were probably told to use induction to prove that your recursive algorithm was correct. (For the purposes of this post, let us exclude hairy recursive functions like the one in the Collatz conjecture which do not obviously terminate.) Induction suspiciously resembles recursion: the similarity comes from the fact that the inductive hypothesis looks a bit like the result of a “recursive call” to the theorem you are proving. If an ordinary recursive computation returns plain old values, you might wonder if an “induction computation” returns proof terms (which, by the Curry-Howard correspondence, could be thought of as a value).

As it turns out, however, when you look at recursion and induction categorically, they are not equivalent! Intuitively, the difference lies in the fact that when you are performing induction, the data type you are performing induction over (e.g. the numbers) appears at the type level, not the term level. In the words of a category theorist, both recursion and induction have associated initial algebras, but the carrier sets and endofunctors are different. In this blog post, I hope to elucidate precisely what the difference between recursion and induction is. Unfortunately, I need to assume some familiarity with initial algebras: if you don’t know what the relationship between a fold and an initial algebra is, check out this derivation of lists in initial algebra form.

When dealing with generalized abstract nonsense, the most important first step is to use a concrete example! So let us go with the simplest nontrivial data type one can gin up: the natural numbers (our examples are written in both Coq and Haskell, when possible):

Inductive nat : Set := (* defined in standard library *) | 0 : nat | S : nat -> nat. data Nat = Z | S Nat

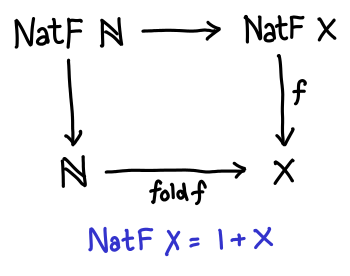

Natural numbers are a pretty good example: even the Wikipedia article on F-algebras uses them. To recap, an F-algebra (or sometimes simply “algebra”) has three components: an (endo)functor f, a type a and a reduction function f a -> a. For simple recursion over natural numbers, we need to define a functor NatF which “generates” the natural numbers; then our type a is Nat and the reduction function is type NatF Nat -> Nat. The functor is defined as follows:

Inductive NatF (x : Set) : Set := | F0 : NatF x. | FS : x -> NatF x. data NatF x = FZ | FS x

Essentially, take the original definition but replace any recursive occurrence of the type with a polymorphic variable. As an exercise, show that NatF Nat -> Nat exists: it is the (co)product of () -> Nat and Nat -> Nat. The initiality of this algebra implies that any function of type NatF x -> x (for some arbitrary type x) can be used in a fold Nat -> x: this fold is the homomorphism from the initial algebra (NatF Nat -> Nat) to another algebra (NatF x -> x). The take-away point is that the initial algebra of natural numbers consists of an endofunctor over sets.

Let’s look at the F-algebra for induction now. As a first try, let’s try to use the same F-algebra and see if an appropriate homomorphism exists with the “type of induction”. (We can’t write this in Haskell, so now the examples will be Coq only.) Suppose we are trying to prove some proposition P : nat -> Prop holds for all natural numbers; then the type of the final proof term must be forall n : nat, P n. We can now write out the morphism of the algebra: NatF (forall n : nat, P n) -> forall n : nat, P n. But this “inductive principle” is both nonsense and not true:

Hint Constructors nat NatF. Goal ~ (forall (P : nat -> Prop), (NatF (forall n : nat, P n) -> forall n : nat, P n)). intro H; specialize (H (fun n => False)); auto. Qed.

(Side note: you might say that this proof fails because I’ve provided a predicate which is false over all natural numbers. But induction still “works” even when the predicate you’re trying to prove is false: you should fail when trying to provide the base case or inductive hypothesis!)

We step back and now wonder, “So, what’s the right algebra?” It should be pretty clear that our endofunctor is wrong. Fortunately, we can get a clue for what the right endofunctor might be by inspecting the type the induction principle for natural numbers:

(* Check nat_ind. *) nat_ind : forall P : nat -> Prop, P 0 -> (forall n : nat, P n -> P (S n)) -> forall n : nat, P n

P 0 is the type of the base case, and forall n : nat, P n -> P (S n) is the type of the inductive case. In much the same way that we defined NatF nat -> nat for natural numbers, which was the combination of zero : unit -> nat and succ : nat -> nat, we need to define a single function which combines the base case and the inductive case. This seems tough: the result types are not the same. But dependent types come to the rescue: the type we are looking for is:

fun (P : nat -> Prop) => forall n : nat, match n with 0 => True | S n' => P n' end -> P n

You can read this type as follows: I will give you a proof object of type P n for any n. If n is 0, I will give you this proof object with no further help (True -> P 0). However, if n is S n', I will require you to furnish me with P n' (P n' -> P (S n')).

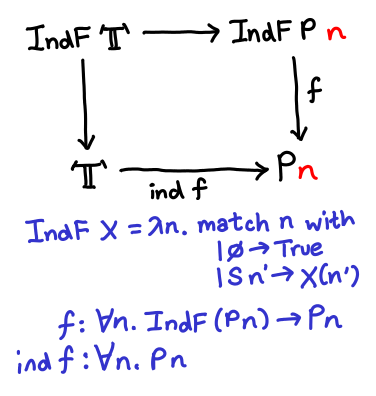

We’re getting close. If this is the morphism of an initial algebra, then the functor IndF must be:

fun (P : nat -> Prop) => forall n : nat, match n with 0 => True | S n' => P n' end

What category is this a functor over? Unfortunately, neither this post nor my brain has the space to give a rigorous treatment, but roughly the category can be thought of as nat-indexed propositions. Objects of this category are of the form forall n : nat, P n, morphisms of the category are of the form forall n : nat, P n -> P' n. [1] As an exercise, show that identity and composition exist and obey the appropriate laws.

Something amazing is about to happen. We have defined our functor, and we are now in search of the initial algebra. As was the case for natural numbers, the initial algebra is defined by the least fixed point over the functor:

Fixpoint P (n : nat) : Prop := match n with 0 => True | S n' => P n' end.

But this is just True!

Hint Unfold P. Goal forall n, P n = True. induction n; auto. Qed.

Drawing out our diagram:

The algebras of our category (downward arrows) correspond to inductive arguments. Because our morphisms take the form of forall n, P n -> P' n, one cannot trivially conclude forall n, P' n simply given forall n, P n; however, the presence of the initial algebra means that True -> forall n, P n whenever we have an algebra forall n, IndF n -> P n. Stunning! (As a side note, Lambek’s lemma states that Mu P is isomorphic to P (Mu P), so the initial algebra is in fact really really trivial.)

In conclusion:

- Recursion over the natural numbers involves F-algebras with the functor unit + X over the category of Sets. The least fixed point of this functor is the natural numbers, and the morphism induced by the initial algebra corresponds to a fold.

- Induction over the natural numbers involves F-algebras with the functor fun n => match n with 0 => True | S n' => P n' over the category of nat-indexed propositions. The least fixed point of this functor is True, and the morphism induced by the initial algebra establishes the truth of the proposition being inductively proven.

So, the next time someone tells asks you what the difference between induction and recursion is, tell them: Induction is just the unique homomorphism induced by an initial algebra over indexed propositions, what’s the problem?

Acknowledgements go to Conor McBride, who explained this shindig to me over ICFP. I promised to blog about it, but forgot, and ended up having to rederive it all over again.

[1] Another plausible formulation of morphisms goes (forall n : nat, P n) -> (forall n : nat, P' n). However, morphisms in this category are too strong: they require you to go and prove the result for all n... which you would do with induction, which misses the point. Plus, this category is a subcategory of the ordinary category of propositions.