Duality for Haskellers

This post is the spiritual predecessor to Flipping Burgers in coBurger King.

What does it mean for something to be dual? A category theorist would say, “It’s the same thing, but with all the arrows flipped around.” This answer seems frustratingly vague, but actually it’s quite precise. The only thing missing is knowing what arrows flip around! If you know the arrows, then you know how to dualize. In this post, I’d like to take a few structures that are well known to Haskellers, describe what the arrows for this structure look like, and then show that when we flip the arrows, we get a dual concept.

Products and sums

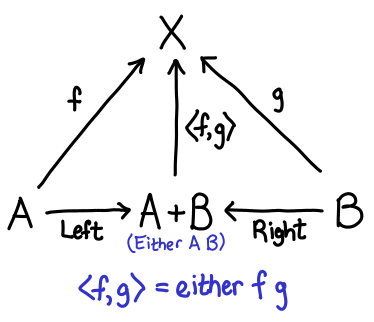

Suppose you have some data of the type Either a b. With all data, there are two fundamental operations we would like to perform on them: we’d like to be able to construct it and destruct it. The constructors of Either are the Left :: a -> Either a b and Right :: b -> Either a b, while a reasonable choice of destructor might be either :: (a -> r) -> (b -> r) -> Either a b -> r (case analysis, where the first argument is the Left case, and the second argument is the Right case). Let’s draw a diagram:

I’ve added in two extra arrows: the represent the fact that either f g . Left == f and either f g . Right == g; these equations in some sense characterize the relationship between the constructor and destructor.

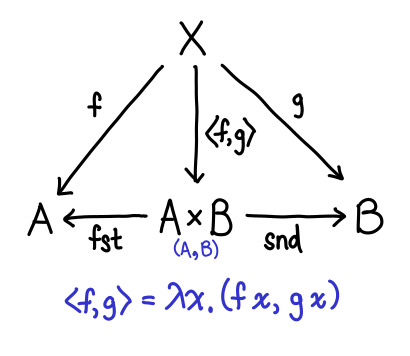

OK, so what happens when we flip these arrows around? The title of this section has given it away, but let’s look at it:

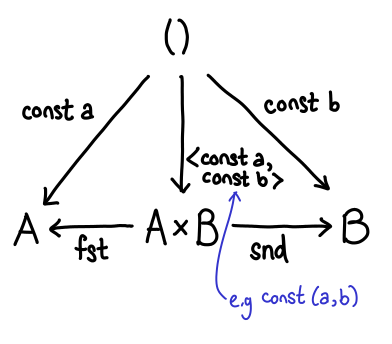

Some of these arrows are pretty easy to explain. What used to be our constructors (Left and Right) are now our destructors (fst and snd). But what of f and g and our new constructor? In fact, \x -> (f x, g x) is in some sense a generalized constructor for pairs, since if we set f = const a and g = const b we can easily get a traditional constructor for a pair (where the specification of the pair itself is the arrow—a little surprising, when you first see it):

So, sums and products are dual to each other. For this reason, sums are often called coproducts.

(Keen readers may have noticed that this presentation is backwards. This is mostly to avoid introducing \x -> (f x, g x), which seemingly comes out of nowhere.)

Top and bottom

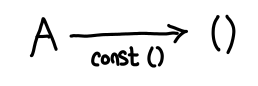

The unit type (referred to as top) and the bottom type (with no inhabitants) exhibit a duality between one another. We can see this as follows: for any Haskell type, I can trivially construct a function which takes a value of that type and produces unit; it’s const ():

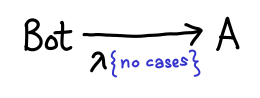

Furthermore, ignoring laziness, this is the only function which does this trick: it’s unique. Let’s flip these arrows around: does there exist a type A for which for any type B, there exists a function A -> B? At first glance, this would seem impossible. B could be anything, including an uninhabited type, in which case we’d be hard pressed to produce anything of the appropriate value. But wait: if A is uninhabited, then I don’t have to do anything: it’s impossible for the function to be invoked!

Thus, top and bottom are dual to one another. In fact, they correspond to the concepts of a terminal object and an initial object (respectively) in the category Hask.

One important note about terminal objects: is Int a terminal object? It is certainly true that there are functions which have the type forall a. a -> Int (e.g. const 2). However, this function is not unique: there's const 0, const 1, etc. So Int is not terminal. For good reason too: there is an easy to prove theorem that states that all terminal objects are isomorphic to one another (dualized: all initial objects are isomorphic to one another), and Int and () are very obviously not isomorphic!

Folds and unfolds

One of the most important components of a functional programming language is the recursive data structure (also known as the inductive data structure). There are many ways to operate on this data, but one of the simplest and most well studied is the fold, possibly the simplest form a recursion one can use.

The diagram for a fold is a bit involved, so we’ll derive it from scratch by thinking about the most common fold known to functional programmers, the fold on lists:

data List a = Cons a (List a) | Nil foldr :: (a -> r -> r) -> r -> List a -> r

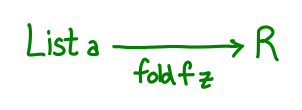

The first two arguments “define” the fold, while the third argument simply provides the list to actually fold over. We could try to draw a diagram immediately:

But we run into a little bit of trouble: our diagram is a bit boring, mostly because the pair (a -> r -> r, r) doesn’t really have any good interpretation as an arrow. So what are we to do? What we’d really like is a single function which encodes all of the information that our pair originally encoded.

Well, here’s one: g :: Maybe (a, r) -> r. Supposing we originally had the pair (f, z), then define g to be the following:

g (Just (x, xs)) = f x xs g Nothing = z

Intuitively, we’ve jammed the folding function and the initial value into one function by replacing the input argument with a sum type. To run f, we pass a Just; to get z, we pass a Nothing. Generalizing a bit, any fold function can be specified with a function g :: F a r -> r, where F a is a functor suitable for the data type in question (in the case of lists, type F a r = Maybe (a, r).) We reused Maybe so that we didn’t have to define a new data type, but we can rename Just and Nothing a little more suggestively, as data ListF a r = ConsF a r | NilF. Compared to our original List definition (Cons a (List a) | Nil), it’s identical, but with all the recursive occurrences of List a replaced with r.

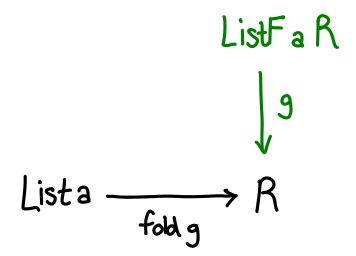

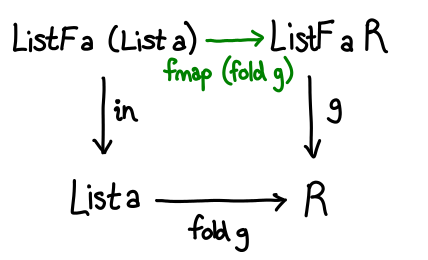

With this definition in hand, we can build out our diagram a bit more:

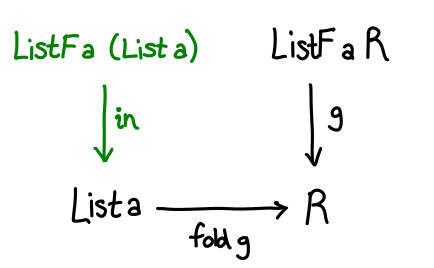

The last step is to somehow relate List a and ListF a r. Remember how ListF looks a lot like List, just with r replacing List a. So what if we had ListF a (List a)—literally substituting List a back into the functor. We’d expect this to be related to List a, and indeed there’s a simple, unique function which converts one to the other:

in :: ListF a (List a) -> List a in (ConsF x xs) = Cons x xs in NilF = Nil

There’s one last piece to the puzzle: how do we convert from ListF a (List a) to ListF a r? Well, we already have a function fold g :: List a -> r, so all we need to do is lift it up with fmap.

We have a commuting diagram, and require that g . fmap (fold g) = fold g . in.

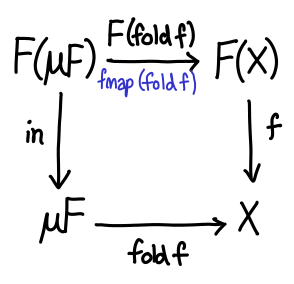

All that’s left now is to generalize. In general, ListF and List are related using little trick called the Mu operator, defined data Mu f = Mu (f (Mu f)). Mu (ListF a) is isomorphic to List a; intuitively, it replaces all instances of r with the data structure you are defining. So in general, the diagram looks like this:

Now that all of these preliminaries are out of the way, let’s dualize!

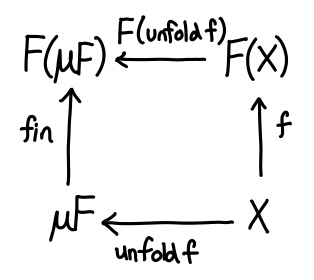

If we take a peek at the definition of unfold in Prelude: unfold :: (b -> Maybe (a, b)) -> b -> [a]; the Maybe (a, b) is exactly our ListF!

The story here is quite similar to the story of sums and products: in the recursive world, we were primarily concerned with how to destruct data. In the corecursive world, we are primarily concerned with how to construct data: g :: r -> F r, which now tells us how to go from r into a larger Mu F.

Conclusion

Dualization is an elegant mathematical concept which shows up everywhere, once you know where to look for it! Furthermore, it is quite nice from the perspective of a category theorist, because when you know two concepts are dual, all the theorems you have on one side flip over to the other side, for free! (This is because all of the fundamental concepts in category theory can be dualized.) If you’re interested in finding out more, I recommend Dan Piponi’s article on data and codata.