IVar leaks

The first thing to convince yourself of is that there actually is a problem with the code I posted last week. Since this is a memory leak, we need to keep track of creations and accesses of IVars. An IVar allocation occurs in the following cases for our example:

- Invocation of return, which returns a full IVar,

- Invocation of tick, which returns an empty IVar and schedules a thread to fill this IVar, and

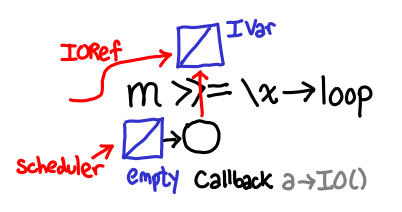

- Invocation of >>=, which returns an empty IVar and a reference to this IVar in the callback attached to the left-hand IVar.

An IVar access occurs when we dereference an IORef, add a callback or fill the IVar. This occurs in these cases:

- Invocation of >>=, which dereferences the left IVar and adds a callback,

- Invocation of the callback on the left argument of >>=, which adds a callback to the result of f x,

- Invocation of the callback on the result of f x (from the above callback), which fills the original IVar allocated in (3), and

- Invocation of the scheduled thread by tick, which fills the empty IVar it was scheduled with.

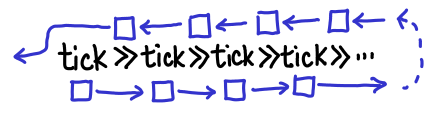

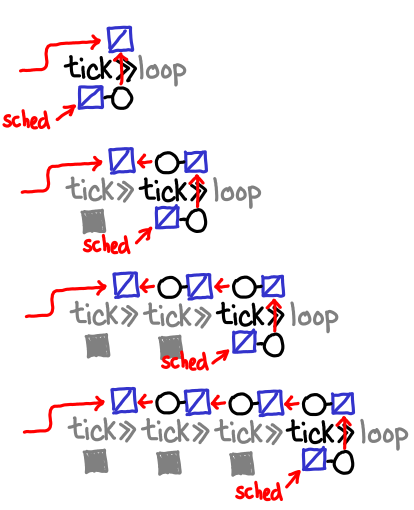

We can now trace the life-cycle of an IVar allocated by the >>= in the code loop = tick >>= loop.

IVar allocated by >>=. Two references are generated: one in the callback attached to tick and one returned.

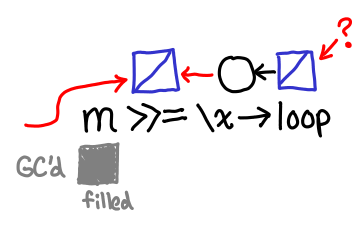

Scheduler runs thread that fills in IVar from tick, its callback is run. IVar is reachable via the newly allocated callback attached to f x. Note that f in this case is \() -> loop, so at this point the recursive call occurs.

Scheduler runs thread that fills in IVar from f x, its callback is run. IVar is filled in, and the reference to it in the callback chain is now dead. Life of the IVar depends solely on the reference that we returned to the client.

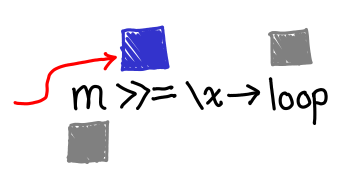

Notice that across the first and second scheduler rounds, the bind-allocated IVar is kept alive by means other than the reference we returned to the client. In the first case it’s kept alive by the callback to tick (which is in turn kept alive by its place in the execution schedule); in the second case it’s kept alive by the callback to f x. If we can get to the third case, everything will manage to get GC'd, but that’s a big if: in our infinite loop, f x is never filled in.

Even if it does eventually get filled in, we build up an IVar of depth the length of recursion, whereas if we had some sort of “tail call optimization”, we could immediately throw these IVars away.