Bindings and CAFs on the Haskell Heap

Today, we discuss how presents on the Haskell Heap are named, whether by top-level bindings, let-bindings or arguments. We introduce the Expression-Present Equivalent Exchange, which highlights the fact that expressions are also thunks on the Haskell heap. Finally, we explain how this let-bindings inside functions can result in the creation of more presents, as opposed to constant applicative forms (CAFs) which exist on the Haskell Heap from the very beginning of execution.

When we’ve depicted presents on the Haskell Heap, they usually have names.

We’ve been a bit hush-hush about where these names come from, however. Partially, this is because the source of most of these names is straight-forward: they’re simply top-level bindings in a Haskell program:

y = 1 maxDiameter = 100

We also have names that come as bindings for arguments to a function. We’ve also discussed these when we talked about functions. You insert a label into the machine, and that label is how the ghost knows what the “real” location of x is:

f x = x + 3 pred = \x -> x == 2

So if I write f maxDiameter the ghost knows that wherever it sees x it should instead look for maxDiameter. But this explanation has some gaps in it. What if I write f (x + 2): what’s the label for x + 2?

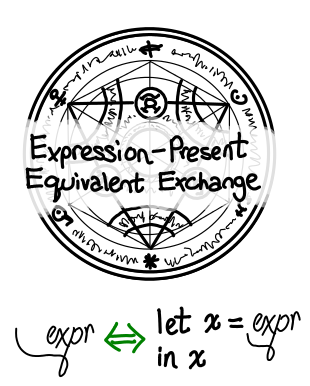

One way to look at this is to rewrite this function in a different way: let z = x + 2 in f z, where z is a fresh variable: one that doesn’t show up anywhere else in the expression. So, as long as we understand what let does, we understand what the compact f (x + 2) does. I’ll call this the Expression-Present Equivalent Exchange.

But what does let do anyway?

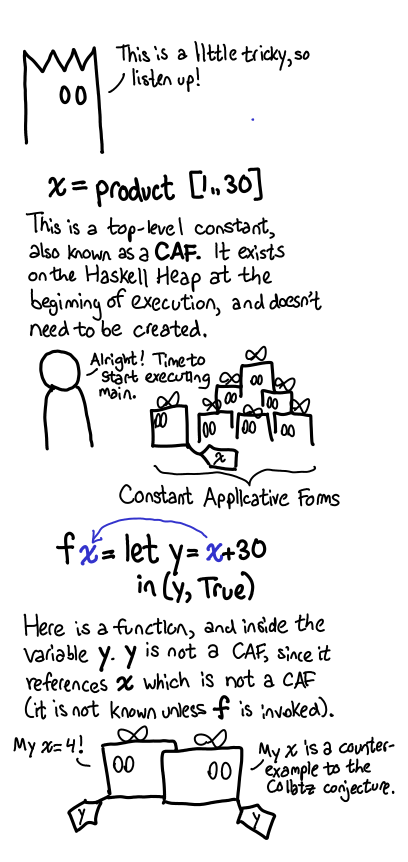

Sometimes, exactly the same job as a top-level binding. These are Constant Applicative Forms (CAF).

So we just promote the variable to the global heap, give it some unique name and then it’s just like the original situation. We don’t even need to re-evaluate it on a subsequent call to the function. To reiterate, the key difference is free variables (see bottom of post for a glossary): a constant-applicative form has no free variables, whereas most let bindings we write have free variables.

Glossary. The definition of free variables is pretty useful, even if you’ve never studied the lambda calculus. The free variables of an expression are variables for which I don’t know the value of simply by looking at the expression. In the expression x + y, x and y are free variables. They’re called free variables because a lambda “captures” them: the x in \x -> x is not free, because it is defined by the lambda \x ->. Formally:

fv(x) = {x} fv(e1 e2) = fv(e1) `union` fv(e2) fv(\x -> e1) = fv(e1) - {x}

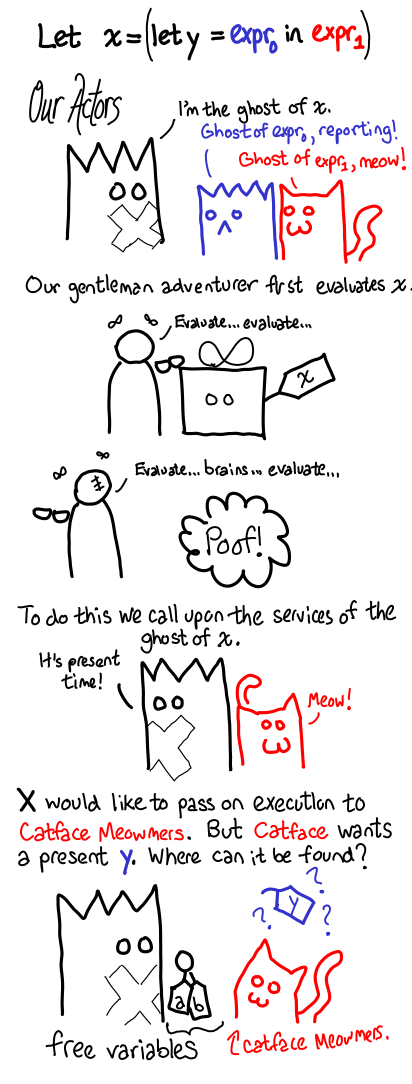

If we do have free variables, things are a little trickier. So here is an extended comic explaining what happens when you force a thunk that is a let binding.

Notice how the ghosts pass the free variables around. When a thunk is left unevaluated, the most important things to look at are its free variables, as those are the other thunks that will have been left unevaluated. It’s also worth repeating that functions always take labels of presents, never actual unopened presents themselves.

The rules are very simple, but the interactions can be complex!

Last time: How the Grinch stole the Haskell Heap

Technical notes. When writing strict mini-languages, a common trick when implementing let is to realize that it is actually syntax sugar for lambda application: let x = y in z is the same as (\x -> z) y. But this doesn’t work for lazy languages: what if y refers to x? In this case, we have a recursive let binding, and usually you need to use a special let-rec construction instead, which requires some mutation. But in a lazy language, it’s easy: making the binding will never evaluate the right-hand side of the equation, so I can set up each variable at my leisure. I also chose to do the presentation in the opposite way because I want people to always be thinking of names. CAFs don’t have names, but for all intents and purposes they’re global data that does get shared, and so naming it is useful if you’re trying to debug a CAF-related space leak.

Perhaps a more accurate translation for f (x + 2) is f (let y = x + 2 in y), but I thought that looked kind of strange. My apologies.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.