Someone is wrong on the Internet

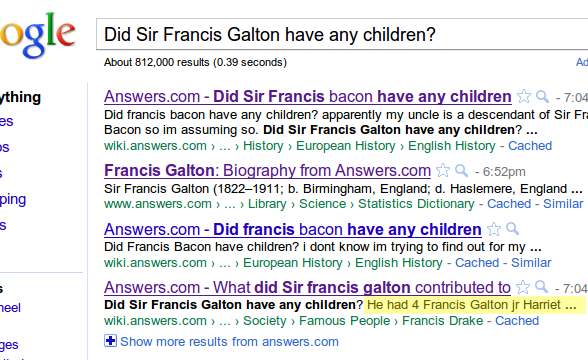

Suppose you have a Random Question™ that you would like answered. For example, “Did Sir Francis Galton have any children?” It’s the type of thing you’d type into Google.

Answers.com is not a terribly good source, but it is something to at least see if you can scrounge up some extra information on. So suppose you dig a little deeper and discover that Francis Galton only married once and that this marriage was barren. So unless some historian’s account of Galton suffering from venereal disease (Kevles 12) indicates that he knocked up some ladies in Syria and managed to pop out four offspring, who happened to conveniently be named “Francis, Harriet, Matilda and Mark,” Answers.com is wrong.

Not really surprising. But that’s not what this essay is about.

What this essay is about is what you’re supposed to do when you encounter flagrant and unabashed misinformation on the Internet: that is, someone is wrong on the Internet. There are a few obvious answers:

- Disseminate corrective information,

- Fix it, or

- Ignore it.

Disseminating corrective information is really just a glorified term for “arguing”. And everyone knows that arguing on the Internet is perhaps one of the most undignified occupations one can assume. Nevertheless, it is an important mechanism for correcting incorrect information. As Djerassi once said (and I paraphrase), only a masochist would get into an argument with a fundamentalist about evolution, yet we would be much worse off if we had no such masochists willing to engage in this debate. For less contentious issues, the formula of the “dispelling myths” essay is a popular mechanism of presenting interesting, corrective information to a receptive audience.

I think the primary difficulties with this approach can be summed up in three words: cost, effectiveness and reach.

- Cost. Writing up an effective rebuttal takes time. Arguing is a time-consuming activity. If it’s not something you particularly care about, it makes much more sense to update your own belief structure, and not bother attempting to convince other people about your updated belief.

- Effectiveness. The truism is that “arguing with someone on the Internet is like arguing with a pig: it frustrates you and irritates the pig.” But social psychology research paints an even more troubling picture: even if you manage to convince someone that you’re right, they’re old (falsified) belief can still affect their decision making process. Not only that, but true information may cause a person to believe more strongly in their false beliefs. Why bother?

- Reach. Even if you write a stunning argument that convinces everyone who reads it, there is still the problem of dissemination. The Internet makes it extremely easy to pick and choose what you want to read, to aggregate news from like-minded individuals, a phenomenon Ethan Zuckerman calls homophily. The fear is that we get caught up in our own comfortable information loops, making us much dumber.

The notion that you might be able to directly fix it seems to be a relatively recent one, come with the advent of wikis and the social web. Perhaps the ability to unrestrictedly edit an incorrect information source is a new, but the ability to go to the source, to write a letter to the editor of a textbook, is one that has been around for a long time. There is something of a glorious tradition here, including things like Knuth’s reward checks that offer fame and minuscule amounts of money for those who find errors. Sure you might need to argue with one person, but that’s all you need, and afterwards, the original infelicity is corrected.

When you go to the source, you partially resolve the reach problem: new readers instantly have access to the corrected text (though this doesn’t do much for existing dead-tree copies). But cost and effectiveness are still present; perhaps even exacerbated. You have to convince a single person that you’re right; if you can’t manage that, you’ll have to fall back to a separate rebuttal. Sometimes content is abandoned, with the original author having no intention of updating it.

Unrestricted edit access has also given rise to edit warring. In this situation, you have to actively defend the modification you have made, and unfortunately, the winner is usually the one who has more time and resources. Edit warring is war by attrition,.

Aside. There are some parallels with the world of open-source software. Fixing it is analogous to submitting a bug report or a patch; the need to convince the maintainers you are right translates into the act of writing a good bug report. If a project is abandoned, you're out of luck; even if it’s not abandoned, you need to make the maintainer care about your specific problem. To fork is to disseminate corrective information, although there is an element of unrestricted edits mixed in with social coding websites that make it easy to find related copies.

Or you can not bother, and just ignore it. Maybe vent a little about the problem to your friends, who have no particular stake in the matter, file it away in your brain, and let life go on. In fact, this is precisely the disposition I see adopted by most of my colleagues. They don’t write for the public. They are more than happy to share their vast warehouse of knowledge and insights with their friends, with whom the exchange is usually effective and the cost not very high (they prefer informal mediums like face-to-face conversations and instant-messaging).

In fact, I’d hazard that only a fraction of what you might call the literati and experts of the world prolifically utilize this sort of broad-net information dissemination, that sites like Wikipedia, StackOverflow and Quora attempt to exploit. The incentive structure is simply not there! For the academic, communication with the general public is secondary to communication with your peers and your funders. For the entrepreneur, communication with your customers, and not the sort of communication we see here, is what is valued. For the software engineer, communication with upstream is beneficial insofar as it lets you stop maintaining your bug fixes. The mind boggles at how much untapped expertise there is out there (perhaps that’s what sites like Quora are going for.)

It would be folly to try to tell them all to not do that. After all, from their point of view, this is what is the most rational use of their time. We can try to trick individuals into pouring this information out, in the form of social incentives and addictive triggers, but by in large I think these individuals will not bite. They’re too clever for that.

Better hope you catch them in a fit of irrationality.