No one expects the Scott induction!

New to this series? Start at the beginning!

Recursion is perhaps one of the first concepts you learn about when you learn functional programming (or, indeed, computer science, one hopes.) The classic example introduced is factorial:

fact :: Int -> Int fact 0 = 1 -- base case fact n = n * fact (pred n) -- recursive case

Recursion on natural numbers is closely related to induction on natural numbers, as is explained here.

One thing that’s interesting about the data type Int in Haskell is that there are no infinities involved, so this definition works perfectly well in a strict language as well as a lazy language. (Remember that Int is a flat data type.) Consider, however, Omega, which we were playing around with in a previous post: in this case, we do have an infinity! Thus, we also need to show that factorial does something sensible when it is passed infinity: it outputs infinity. Fortunately, the definition of factorial is precisely the same for Omega (given the appropriate typeclasses.) But why does it work?

One operational answer is that any given execution of a program will only be able to deal with a finite quantity: we can’t ever actually “see” that a value of type Omega is infinity. Thus if we bound everything by some large number (say, the RAM of our computer), we can use the same reasoning techniques that applied to Int. However, I hope that you find something deeply unsatisfying about this answer: you want to think of an infinite data type as infinite, even if in reality you will never need the infinity. It’s the natural and fluid way to reason about it. As it turns out, there’s an induction principle to go along with this as well: transfinite induction.

Omega is perhaps not a very interesting data type that has infinite values, but there are plenty of examples of infinite data types in Haskell, infinite lists being one particular example. So in fact, we can generalize both the finite and infinite cases for arbitrary data structures as follows:

Scott induction is the punch line: with it, we have a versatile tool for reasoning about the correctness of recursive functions in a lazy language. However, its definition straight up may be a little hard to digest:

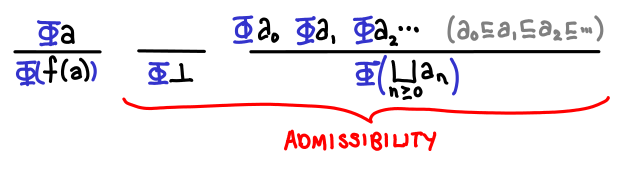

Let D be a cpo. A subset S of D is chain-closed if and only if for all chains in D, if each element of the chain is in S, then the least upper bound of the chain is in S as well. If D is a domain, a subset S is admissible if it is chain-closed and it contains bottom. Scott’s fixed point induction principle states that to prove that fix(f) is in S, we merely need to prove that for all d in D, if d is in S, then f(d) is in S.

When I first learned about Scott induction, I didn’t understand why all of the admissibility stuff was necessary: it was explained to me to be “precisely the stuff necessary to make the induction principle work.” I ended up coming around to this point of view in the end, but it’s a little hard to see in its full generality.

So, in this post, we’ll show how the jump from induction on natural numbers to transfinite induction corresponds to the jump from structural induction to Scott induction.

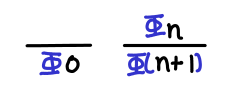

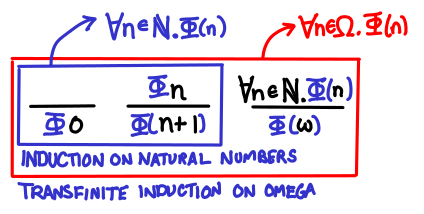

Induction on natural numbers. This is the induction you learn on grade school and is perhaps the simplest form of induction. As a refresher, it states that if some property holds for when n = 0, and if some property holds for n + 1 given that it holds for n, then the property holds for all natural numbers.

One way of thinking of the base case and the inductive step is to see them as inference rules that we need to show are true: if they are, we get another inference rule that lets us sidestep the infinite applications of the inductive step that would be necessary to satisfy ourselves that the property holds for all natural numbers. (Note that there is on problem if we only want to show that the property holds for an arbitrary natural number: that only requires a finite number of applications of the inductive step!)

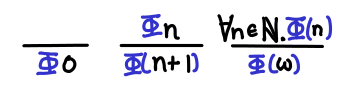

Transfinite induction on Omega. Recall that Omega is the natural numbers plus the smallest infinite ordinal ω. Suppose that we wanted to prove that some property held for all natural numbers as well as infinity. If we just used induction on natural numbers, we’d notice that we’d be able to prove the property for some finite natural number, but not necessarily for infinity (for example, we might conclude that every natural number has another number greater than it, but there is no value in Omega greater than infinity).

This means we need one case: given that a property holds for all natural numbers, it holds for ω as well. Then we can apply induction on natural numbers and then infer that the property holds for infinity as well.

We notice that transfinite induction on Omega requires strictly more cases to be proven than induction on natural numbers, and as such is able to draw stronger conclusions.

Aside. In its full generality, we may have many infinite ordinals, and so the second case generalizes to successor ordinals (e.g. adding 1) and the third case generalizes to limit ordinal (that is, an ordinal that cannot be reached by repeatedly applying the successor function a finite number of times—e.g. infinity from zero). Does this sound familiar? I hope it does: this notion of a limit should remind you of the least upper bounds of chains (indeed, ω is the least upper bound of the only nontrivial chain in the domain Omega).

Let’s take a look at the definition of Scott induction again:

Let D be a cpo. A subset S of D is chain-closed if and only if for all chains in D, if each element of the chain is in S, then the least upper bound of the chain is in S as well. If D is a domain, a subset S is admissible if it is chain-closed and it contains bottom. Scott’s fixed point induction principle states that to prove that fix(f) is in S, we merely need to prove that for all d in D, if d is in S, then f(d) is in S.

We can now pick out the parts of transfinite induction that correspond to statements in this definition. S corresponds to the set of values with the property we want to show, so S = {d | d in D and prop(d)} The base case is the inclusion of bottom in S. The successor case is “if d is in S, then f(d) is in S” (notice that f is our successor function now, not the addition of one). And the limit case corresponds to the chain-closure condition.

Here are all of the inference rules we need to show!

The domain D that we would use to prove that factorial is correct on Omega is the domain of functions Omega -> Omega, the successor function is (Omega -> Omega) -> (Omega -> Omega), and the subset S would correspond to the chain of increasingly defined versions of factorial. With all these ingredients in hand, we can see that fix(f) is indeed the factorial function we are looking for.

There are a number of interesting “quirks” about Scott induction. One is the fact that the property must hold for bottom, which is a partial correctness result (“such and such holds if the program terminates”) rather than a total correctness result (“the program terminates AND such and such holds”). The other is that the successor case is frequently not the most difficult part of a proof involving Scott induction: showing admissibility of your property is.

This concludes our series on denotational semantics. This is by no means complete: usually the next thing to look at is a simple functional programming language called PCF, and then relate the operational semantics and denotational semantics of this language. But even if you decide that you don’t want to hear any more about denotational semantics, I hope these glimpses into this fascinating world will help you reason about laziness in your Haskell programs.

Postscript. I originally wanted to relate all these forms of inductions to generalized induction as presented in TAPL: the inductive principle is that the least fixed point of a monotonic function F : P(U) -> P(U) (where P(U) denotes the powerset of the universe) is the intersection of all F-closed subsets of U. But this lead to the rather interesting situation where the greatest fixed points of functions needed to accept sets of values, and not just a single value. I wasn’t too sure what to make of this, so I left it out.

Unrelatedly, it would also be nice, for pedagogical purposes, to have a “paradox” that arises from incorrectly (but plausibly) applying Scott induction. Alas, such an example eluded me at the time of writing.