Tour of a distributed Erlang application

Bonus post today! Last Tuesday, John Erickson gave a Galois tech talk entitled “Industrial Strength Distributed Explicit Model Checking” (video), in which he describe PReach, an open-source model checker based on Murphi that Intel uses to look for bugs in its models. It is intended as a simpler alternative to Murphi’s built-in distributed capabilities, leveraging Erlang to achieve much simpler network communication code.

First question. Why do you care?

- Model checking is cool. Imagine you have a complicated set of interacting parallel processes that evolve nondeterministically over time, using some protocol to communicate with each other. You think the code is correct, but just to be sure, you add some assertions that check for invariants: perhaps some configurations of states should never be seen, perhaps you want to ensure that your protocol never deadlocks. One way to test this is to run it in the field for a while and report when the invariants fail. Model checking lets you comprehensively test all of the possible state evolutions of the system for deadlocks or violated invariants. With this, you can find subtle bugs and you can find out precisely the inputs that lead to that event.

- Distributed applications are cool. As you might imagine, the number of states that need to be checked explodes exponentially. Model checkers apply algorithms to coalesce common states and reduce the state space, but at some point, if you want to test larger models you will need more machines. PReach has allowed Intel to run the underlying model checker Murphi fifty times faster (with a hundred machines).

This talk was oriented more towards to the challenges that the PReach team encountered when making the core Murphi algorithm distributed than how to model check your application (although I’m sure some Galwegians would have been interested in that aspect too.) I think it gave an excellent high level overview of how you might design a distributed system in Erlang. Since the software is open source, I’ll link to relevant source code lines as we step through the high level implementation of this system.

The algorithm. At its heart, model checking is simply a breadth-first search. You take the initial states, compute their successor states, and add those states to the queue of states to be processed.

WQ : list of state // work queue

V : set of state // visited states

WQ := initial_states()

while !empty(WQ) {

s = dequeue(WQ)

foreach s' in successors(s) {

if !member(s', V) {

check_invariants(s')

enqueue(s', WQ)

add_element(s', V)

}

}

}

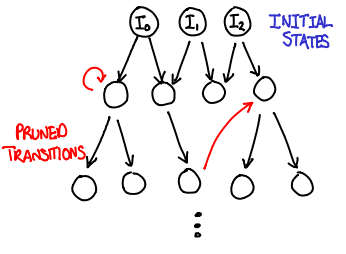

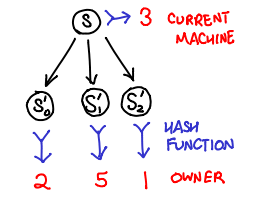

The parallel algorithm. We now need to make this search algorithm parallel. We can duplicate the work queues across computers, making the parallelization a matter of distributing the work load across a number of computers. However, the set of visited states is trickier: if we don’t have a way of partitioning it across machines, it becomes shared state and a bottleneck for the entire process.

Stern and Dill (PS) came up with a clever workaround: use a hash function to distribute states to processors. This has several important implications:

- If the hash function is uniform, we now can distribute work evenly across the machines by splitting up the output space of the function.

- Because the hash function is deterministic, any state will always be sent to the same machine.

- Because states are sticky to machines, each machine can maintain an independent visited states and trust that if a state shows up twice, it will get sent to the same machine and thus show up in the visited states of that machine.

One downside is that a machine cannot save network latency by deciding to process it’s own successor states locally, but this is a fair tradeoff for not having to worry about sharing the visited states, which is considered a hard problem to do efficiently.

The relevant source functions that implement the bulk of this logic are recvStates and reach.

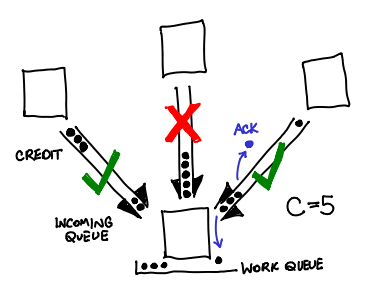

Crediting. When running early versions of PReach, the PReach developers would notice that occasionally a machine in the cluster would massively slow down or crash nondeterministically.

It was discovered that this machine was getting swamped by incoming states languishing in the in-memory Erlang request queue: even though the hash function was distributing the messages fairly evenly, if a machine was slightly slower than its friends, it would receive states faster than it could clear out.

To fix this, PReach first implemented a back-off protocol, and then implemented a crediting protocol. The intuition? Don’t send messages to a machine if it hasn’t acknowledged your previous C messages. Every time a message is sent to another machine, a credit is sent along with it; when the machine replies back that it has processed the state, the credit is sent back. If there are no credits, you don’t send any messages. This bounds the number of messages in the queue to be N * C, where N is the number of nodes (usually about a 100 when Intel runs this). To prevent a build-up of pending states in memory when we have no more credits, we save them to disk.

Erickson was uncertain if Erlang had a built-in that performed this functionality; to him it seemed like a fairly fundamental extension for network protocols.

Load balancing. While the distribution of states is uniform, once again, due to a heterogeneous environment, some machines may be able to process states faster than other. If those machines finish all of their states, they may sit idly by, twiddling their thumbs, while the slower machines still work on their queue.

One thing to do when this happens is for the busy nodes to notice that a machine is idling, and send them their states. Erickson referenced some work by Kumar and Mercer (PDF) on the subject. The insight was that overzealous load balancing was just as bad as no load balancing at all: if the balancer attempts to keep all queues exactly the same, it will waste a lot of network time pushing states across the network as the speeds of the machines fluctuate. Instead, only send states when you notice someone with X times less states than you (where X is around 5.)

One question that might come up is this: does moving the states around in this fashion cause our earlier cleverness with visited state checking to stop working? The answer is fortunately no! States on a machine can be in one of two places: the in-memory Erlang receive queue, or the on-disk work queue. When transferring a message from the receive to the work queue, the visited test is performed. When we push states to a slacker, those states are taken from our work queue: the idler just does the invariant checking and state expansion (and also harmlessly happens to add that state to their visited states list).

Recovering shared states. When an invariant fails, how do you create a backtrace that demonstrates the sequence of events that lead to this state? The processing of any given state is scattered across many machines, which need to get stitched together again. The trick is to transfer not only the current state when passing off successors, but also the previous state. The recipient then logs both states to disk. When you want to trace back, you can always look at the previous state and hash it to determine which machine that state came from.

In the field. Intel has used PReach on clusters of up to 256 nodes to test real models of microarchitecture protocols of up to thirty billion states (to Erickson’s knowledge, this is the largest amount of states that any model checker has done on real models.)

Erlang pain. Erickson’s primary complaint with Erlang was that it did not have good profiling facilities for code that interfaced heavily with C++; they would have liked to have performance optimized their code more but found it difficult to pin down where the slowest portions were. Perhaps some Erlang enthusiasts have some comments here?