More fun with Futamura projections

Code written by Anders Kaseorg.

In The Three Projections of Doctor Futamura, Dan Piponi treats non-programmers to an explanation to the Futamura projections, a series of mind-bending applications of partial evaluation. Go over and read it if you haven't already; this post is intended as a spiritual successor to that one, in which we write some Haskell code.

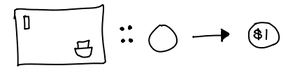

The pictorial type of a mint. In the original post, Piponi drew out machines which took various coins, templates or other machines as inputs, and gave out coins or machines as outputs. Let's rewrite the definition in something that looks a little bit more like a Haskell type.

First, something simple: the very first machine that takes blank coins and mints new coins.

We're now using an arrow to indicate an input-output relationship. In fact, this is just a function that takes blank coins as input, and outputs engraved coins. We can generalize this with the following type synonym:

> type Machine input output = input -> output

What about that let us input the description of the coin? Well, first we need a simple data type to represent this description:

> data Program input output = Program

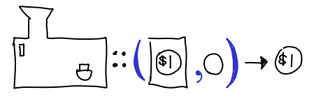

(Yeah, that data-type can't really do anything interesting. We're not actually going to be writing implementations for these machines.) From there, we have our next "type-ified' picture of the interpreter:

Or, in code:

> type Interpreter input output = (Program input output, input) -> output

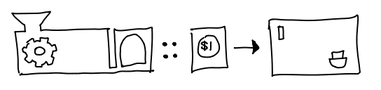

From there, it's not a far fetch to see what the compiler looks like:

> type Compiler input output = Program input output -> Machine input output

I would like to remark that we could have fully written out this type, as such:

type Compiler input output = Program input output -> (input -> output)

We've purposely kept the unnecessary parentheses, since Haskell seductively suggests that you can treat a -> b -> c as a 2-ary function, when we'd like to keep it distinct from (a, b) -> c.

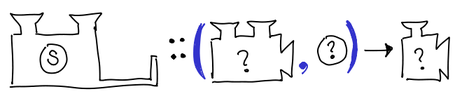

And at last, we have the specializer:

> type Specializer program input output = > ((program, input) -> output, program) -> (input -> output)

We've named the variables in our Specializer type synonym suggestively, but program doesn't just have to be Program: the whole point of the Futamura projections is that we can put different things there. The other interesting thing to note is that any given Specializer needs to be parametrized not just on the input and output, but the program it operates on. That means the concrete type that the Specializer assumes varies depending on what we actually let program be. It does not depend on the first argument of the specializer, which is forced by program, input and output to be (program, input) -> output.

Well, what are those concrete types? For this task, we can ask GHC.

To the fourth projection, and beyond! First, a few preliminaries. We've kept input and output fully general in our type synonyms, but we should actually fill them in with a concrete data type. Some more vacuous definitions:

> data In = In > data Out = Out > > type P = Program In Out > p :: P > p = undefined > > type I = Interpreter In Out > i :: I > i = undefined

We don't actually care how we implement our program or our interpreter, thus the undefined; given our vacuous data definitions, there do exist valid instances of these, but they don't particularly increase insight.

> s :: Specializer program input output > -- s (x, p) i = x (p, i) > s = uncurry curry

We've treated the specializer a little differently: partial evaluation and partial application are very similar: in fact, to the outside user they do precisely the same thing, only partial evaluation ends up being faster because it is actually doing some work, rather than forming a closure, with the intermediate argument hanging around in limbo and not doing any useful work. However, we need to uncurry the curry, since Haskell functions are curried by default.

Now, the Futamura projections:

> type M = Machine In Out > m :: M > m = s1 (i, p)

Without the monomorphism restriction, s would have worked just as well, but we're going to give s1 an explicit type shortly, and that would spoil the fun for the rest of the projections. (Actually, since we gave s an explicit type, the monomorphism restriction wouldn't apply.)

So, what is the type of s1? It's definitely not general: i and p are fully explicit, and Specializer doesn't introduce any other polymorphic types. This should be pretty easy to tell, but we'll ask GHC just in case:

Main> :t s1 s1 :: ((P, In) -> Out, P) -> In -> Out

Of course. It matches up with our variable names!

> type S1 = Specializer P In Out > s1 :: S1 > s1 = s

Time for the second Futamura projection:

> type C = Compiler In Out > c :: C > c = s2 (s1, i)

Notice I've written s2 this time around. That's because `` s1 (s1, i)`` doesn't typecheck; if you do the unification you'll see the concrete types don't line up. So what's the concrete type of s2? A little more head-scratching, and perhaps a quick glance at Piponi's article will elucidate the answer:

> type S2 = Specializer I P M > s2 :: S2 > s2 = s

The third Futamura projection, the interpreter-to-compiler machine:

> type IC = I -> C > ic :: IC > ic = s3 (s2, s1)

(You should verify that s2 (s2, s1) and s1 (s1, s2) and any permutation thereof doesn't typecheck.) We've also managed to lose any direct grounding with the concrete:: there's no p or i to be seen. But s2 and s1 are definitely concrete types, as we've shown earlier, and GHC can do the unification for us:

Main> :t s3 s3 :: ((S1, I) -> C, S1) -> I -> Program In Out -> In -> Out

In fact, it's been so kind as to substitute some of the more gnarly types with the relevant type synonyms for our pleasure. If we add some more parentheses and take only the output:

I -> (Program In Out -> (In -> Out))

And there's our interpreter-to-compiler machine!

> type S3 = Specializer S1 I C > s3 :: S3 > s3 = s

But why stop there?

> s1ic :: S1 -> IC > s1ic = s4 (s3, s2) > > type S4 = Specializer S2 S1 IC > s4 :: S4 > s4 = s

Or even there?

> s2ic :: S2 -> (S1 -> IC) > s2ic = s5 (s4, s3) > > type S5 = Specializer S3 S2 (S1 -> IC) > s5 :: S5 > s5 = s > > s3ic :: S3 -> (S2 -> (S1 -> IC)) > s3ic = s6 (s5, s4) > > type S6 = Specializer S4 S3 (S2 -> (S1 -> IC)) > s6 :: S6 > s6 = s

And we could go on and on, constructing the nth projection using the specializers we used for the n-1 and n-2 projections.

This might seem like a big bunch of type-wankery. I don't think it's just that.

Implementors of partial evaluators care, because this represents a mechanism for composition of partial evaluators. S2 and S1 could be different kinds of specializers, with their own strengths and weaknesses. It also is a vivid demonstration of one philosophical challenge of the partial-evaluator writer: they need to write a single piece of code that can work on arbitrary n in Sn. Perhaps in practice it only needs to work well on low n, but the fact that it works at all is an impressive technical feat.

For disciples of partial application, this is something of a parlor trick:

*Main> :t s (s,s) s s (s,s) s :: ((program, input) -> output) -> program -> input -> output *Main> :t s (s,s) s s s (s,s) s s :: ((input, input1) -> output) -> input -> input1 -> output *Main> :t s (s,s) s s s s (s,s) s s s :: ((input, input1) -> output) -> input -> input1 -> output *Main> :t s (s,s) s s s s s (s,s) s s s s :: ((input, input1) -> output) -> input -> input1 -> output *Main> :t s (s,s) s s s s s s (s,s) s s s s s :: ((input, input1) -> output) -> input -> input1 -> output

But this is a useful parlor trick: somehow we've managed to make an arbitrarily variadic function! I'm sure this technique is being used somewhere in the wild, although as of writing I couldn't find any examples of it (Text.Printf might, although it was tough to tell this apart from their typeclass trickery.)